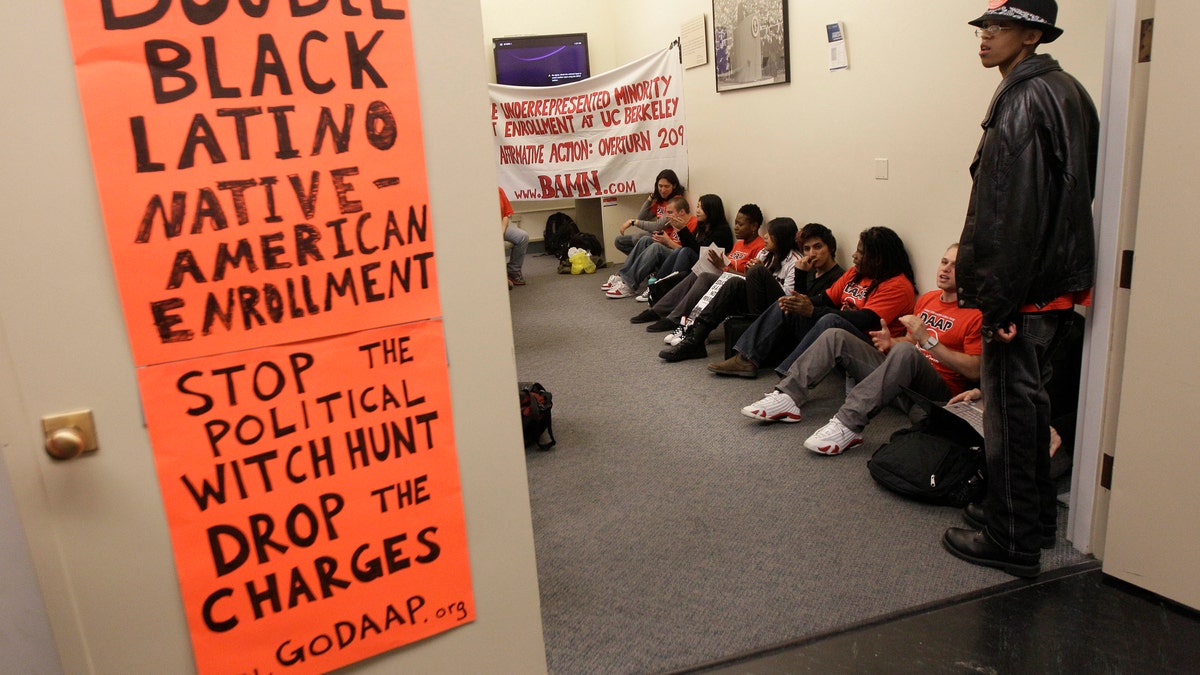

April 6, 2012: In this photo, protesters and students stage a sit in protest at the Sproul Hall Student Services Office at the University of California in Berkeley, Calif.

BERKELEY, California – Fifteen years ago, California voters were asked: Should colleges consider a student's race when they decide who gets in and who doesn't?

With an emphatic "no," they made California the first state to ban the use of race and ethnicity in public university admissions, as well as hiring and contracting.

Since then, California's most selective public colleges and graduate schools have struggled to assemble student bodies that reflect the state's demographic mix.

Universities around the U.S. could soon face the same challenge. The U.S. Supreme Court is set to revisit the thorny issue of affirmative action less than a decade after it endorsed the use of race as a factor in college admissions.

The high court agreed in February to take up the case of a white woman who claims she was rejected by the University of Texas because of its race-conscious admissions policy. The justices are expected to hear arguments this fall.

College officials are worried that today's more conservative court could limit or even ban the consideration of race in admissions decisions. A broad ruling could affect both public and private universities that practice affirmative action, a powerful tool for increasing campus diversity.

"If the decision is very broad and very hostile to affirmative action, the future of the rest of country may look very similar to California," said Barmak Nassirian, associate executive director of the American Association of College Registrars and Admissions Officers. "It would be very disruptive at many institutions."

The effects of California's ban, known as Proposition 209, are particularly evident at the world-renowned University of California, Berkeley campus, where the student body is highly diverse but hardly resembles the ethnic and racial fabric of the state.

With affirmative action outlawed, Asian American students have dominated admissions. The freshman class admitted to UC Berkeley this coming fall is 30 percent white and 46 percent Asian, according to newly released data. The share of admitted Asians is four times higher than their percentage in the state's kindergarten to 12th grade public schools.

But traditionally underrepresented Hispanic and black students remain so. In a state where Latinos make up half the K-12 public school population, only 15 percent of the Berkeley students are Hispanic. And the freshman class is less than 4 percent African Americans, although they make up 7 percent of the K-12 students.

Junior Magali Flores, 20, said she experienced culture shock when she arrived on the Berkeley campus in 2009 after graduating from a predominantly Latino high school in Los Angeles.

Flores, one of five children of working-class parents from Mexico, said she feels the university can feel hostile to students of color, causing some to leave because they don't feel welcome at Berkeley.

"We want to see more of our people on campus," Flores said. "With diversity, more people would be tolerant and understanding of different ethnicities, different cultures."

UC Berkeley has tried to bolster diversity by expanding outreach to high schools in poor neighborhoods and considering applicants' achievements in light of the academic opportunities available to them.

But officials say it's hard to find large numbers of underrepresented minorities competitive enough for Berkeley, where only about one in five applicants are offered spots in the freshman class.

In addition, California's highest-achieving minority students are heavily recruited by top private colleges that practice affirmative action and offer scholarships to minorities, administrators say.

"It's frustrating," said Harry Le Grande, vice chancellor of student affairs at Berkeley. "Many times we lose them to elite privates that can actually take race into account when they admit students."

Backers say affirmative-action policies are needed to combat the legacy of racial discrimination and level the playing field for minorities who are more likely to attend inferior high schools. Colleges benefit from diverse student bodies, and minority students often become leaders in their communities after graduating from top colleges.

"It's critical that our most selective institutions look at least somewhat like the rest of our society," Nassirian said.

Ward Connerly, an African-American businessman who has led a national campaign against affirmative action, sees the practice as a form of racial discrimination.

"I don't believe in proportionality," said Connerly, who heads the American Civil Rights Institute. "The taxpayers have a right to say that we want every kid to be treated without regard to race, color, creed or national origin."

Connerly became wary of UC's efforts to admit more underrepresented minorities when he was a university regent in the 1990s. He pushed the board to bar UC from considering race in school admissions in early 1996 before he helped qualify Proposition 209 for the ballot that year.

"I looked at the extent of our diversity efforts and I concluded we were a lawsuit waiting to happen," Connerly said. "There was a very clear view that we had to be concerned about the growing Asian influence at the University of California."

The year after California's ban took effect, the number of black, Latino and Native American students plummeted by roughly half at Berkeley and UCLA, the UC system's most sought-after campuses.

Voters in Arizona, Michigan, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Washington state and Nebraska have since approved similar bans with similar results.

At the University of Washington, the number of underrepresented minorities dropped by a third after voters banned affirmative action in 1998.

Despite consistent opposition, California's ban has remained enshrined in law. Earlier this month, U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Proposition 209 for the second time. The three-judge panel rejected a legal challenge in which Gov. Jerry Brown joined minority students in arguing the law is unconstitutional.

Affirmative-action advocates say Proposition 209 has created an unfair situation in California, where elite public colleges are dominated by white and Asian students while black and Hispanic students are relegated to less prestigious campuses.

"It is extraordinary that the vast majority of high school graduates in this state are minorities, and they're denied the opportunities to go to their state universities," said attorney Shanta Driver for the group By Any Means Necessary, which filed suit to overturn the ban.

UC officials have tried to increase campus diversity by admitting the top 9 percent of graduates from each high school, conducting a "holistic review" of applications that decreases the weight of standardized test scores and eliminating the requirement to take certain scholastic aptitude exams in individual subjects.

Administrators note the number of Hispanic students at UC's nine undergraduate institutions has been steadily increasing. The California residents admitted to the UC system for this fall are 36 percent Asian American, 28 percent white, 27 percent Hispanic and 4 percent African American, according to the latest figures.

"We're very interested in a diverse student body that reflects the state of California and the nation," said UC provost Larry Pitts. "We have reasonable diversity, but not as much as we would like."