Professor using student ID card tracing to reduce dropouts

Using student 'CatCard' campus location information to trace social behavior, professor says she's able to predict around 90 percent of dropouts

TUSCON, Ariz. – While many schools use grades to determine how to decrease dropout rates, one professor believes that when those grades are released, it’s too late.

Sudha Ram, a management information systems professor at the University of Arizona, found another way to predict whether a student is likely to drop out: a student ID card.

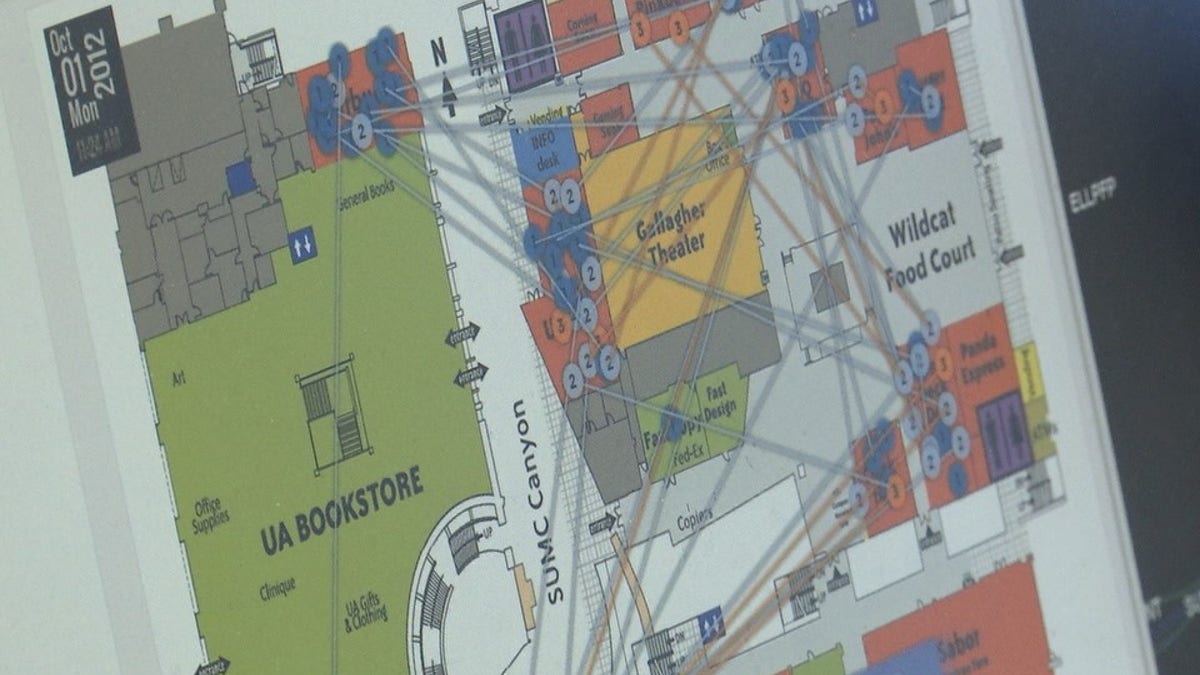

Ram asked the university to anonymize University of Arizona’s student ID cards so that the school could examine where freshman students check in. There are about 700 locations on campus that use the ID cards, including the library, barber shops, the student union, diners and movie theaters.

Ram and her team cull through that information, looking at the time stamp and location ID, to develop algorithms that could predict if students were at risk of dropping out.

Ram and her team cull through that information, looking at the time stamp and location ID, to develop algorithms that could predict if students were at risk of dropping out. (Fox News)

“I know that “A” student checked in at “A” location at a certain time and I can get this list of check-ins,” Ram said. “Then, you can develop some algorithms to glean their social interaction patterns.”

She said you can examine the check-ins over time to see if students have established a routine.

“We’ve developed some innovative algorithms to understand their social interaction patterns and see how they’re changing, week to week,” Ram said. (Fox News)

“We’ve developed some innovative algorithms to understand their social interaction patterns and see how they’re changing, week to week,” she said.

Ram said researchers have found that their predictions are about 90 percent accurate.

"When we bring students into a university, it is our objective to make sure they get the education, the degree they come here for, that we support them in every way."

“This is a serious problem because when we bring students into a university, it is our objective to make sure they get the education, the degree they come here for, that we support them in every way,” Ram said.

But one privacy experts said the project has a lot of potential pitfalls.

“I think the objective is laudable, particular around student retention, particularly in the first year of students and trying to make sure that students who arrive at the university obviously stay there,” said attorney Scott Vernick, who offers guidance to companies on data security and privacy. “But, I think what’s creepy about it, in a ‘big brother’ sort of way, is it’s not clear how transparent the university is about what data they’re collecting: What are they telling parents? What are they telling students? Are they getting consent? Who are they sharing the data with?”

Students on campus seem to have mixed feelings about the data tracking.

Kevin Nguyen, a junior studying systems engineering, thinks it’s a good form of study to track retention rates but also said there’s a lot more that needs to be done for statistical data because not everyone has to use the CatCards. Retention rates at universities is currently at 80 percent, meaning about one in five students drops out.

Kevin Nguyen, a junior studying systems engineering, thinks it’s a good form of study to track retention rates but also feels there’s a lot more that needs to be done for statistical data because not everyone has to use the CatCards. (Fox News)

“I think it’s important to know how retention rate is kind of measured, as well as how to keep retention rate at the University of Arizona because I do know that after the first year of college or second year of college even, a lot of students drop out because either it’s too much work or it’s too hard,” Nguyen said.

But others call it an invasion of privacy.

“It’s so hard to tell when someone says this is anonymous or not when it’s up to them to choose whether your information is confidential or not,” said Ryan Carter, a materials engineering junior at the school.

Ram insists, however, that the information and the students will remain anonymous.

“We have all the permissions from the research board when we started this research,” she said. “We don’t even know who these students are. So, I don’t think we’re tracking students at all. We have an anonymized data set of check-ins with a time stamp.”

Ram is now wanting to work with other public universities to replicate the study, hoping to ultimately raise the retention rate to “almost 100 percent.”

“If we can preserve privacy and yet use data in a way that leads to solutions for challenging social problems,” Ram said, “it’s a very important step in the right direction.”