CrimeCon is the event of the year for diehard crime enthusiasts

Senior correspondent Laura Ingle reports from the convention drawing thousands of 'armchair detectives' to Las Vegas.

Scott Decker, the former FBI special agent on the investigation into the 2001 anthrax attacks, has named one little-recognized hero who "risked his medical career" to save "hundreds, maybe a thousand lives" during the attacks.

The "Amerithrax" attacks, as they are sometimes known, killed five Americans and injured 17 others just weeks after Sept. 11, 2001. American microbiologist Bruce Ivins sent letters laced with anthrax to dozens of U.S. citizens, including members of Congress and a news reporter in Florida before eventually taking his own life.

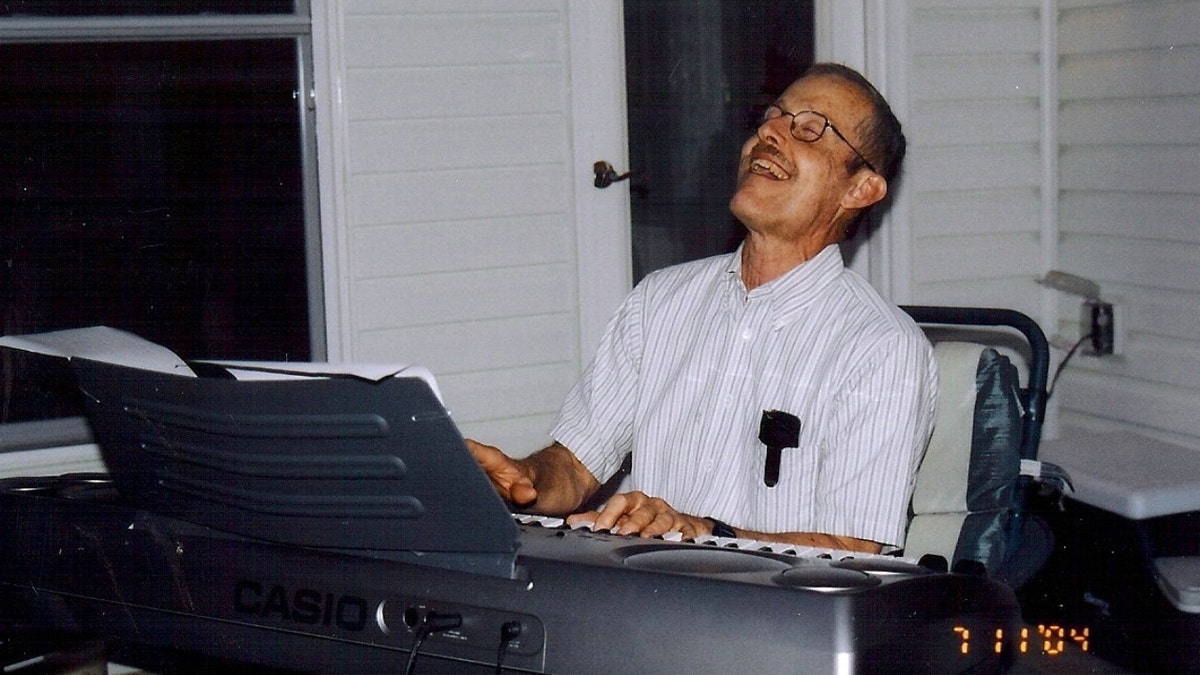

Colleagues remember Bruce Ivins, pictured in this 2004 file photo, playing the keyboard in church and at this office party, but the Justice Department says the Army microbiologist mailed anthrax-filled letters that killed five people in 2001. (U.S. Army Medical Institute of Infectious Diseases, Ft. Detrick, Maryland/Tribune News Service via Getty)

"We had 30 agents all working on the same case. Like the showrunner. It was hard," Decker told Fox News Digital at CrimeCon 2022, a recent true-crime convention in Las Vegas. "First of all, communicating between ourselves was the real challenge. In my book, I try to show how many projects were going on in what we call investigative initiatives on any one day. We had a lot. And for everybody to know what was going on in each program initiative is virtually impossible,"

Decker, who authored the book "Recounting the Anthrax Attacks," had just responded to Ground Zero with the FBI's Hazardous Materials Response Unit before leading the FBI's Amerithrax Task Force. Decker received his doctorate in human genetics from the University of Michigan before completing a postdoctoral fellowship in biological chemistry at Harvard Medical School.

Former FBI Special Agent Scott Decker (Scott Decker)

Once the task force identified the strain of anthrax that killed five Americans and injured 17 others, Decker was assigned to collect samples of every version of the Ames strain that he could find "in the country and throughout the world," seeking a match. Anthrax is a bacterial disease that can be fatal from exposure to the microbe Bacillus anthracis, and the Ames strain was named after the Iowa city where it was first isolated.

The former agent also had to conduct "DNA fingerprinting of the anthrax that was in the envelopes."

A mailbox remains covered in plastic while a U.S. flag flies at half-staff in honor of the two postal employees in Washington who died from anthrax, Oct. 24, 2001, in Hamilton, N.J. (William Thomas Cain)

"And then we would take the fingerprint from the Ames that was in the envelope — hopefully, it would be unique — and compare it to all the samples collected. And if we get a match to find out where that sample came from, we go and get the guy or girl who [belongs to the] sample," Decker explained.

In 2009, Decker's team received the FBI Director's Award for Outstanding Scientific Advancement.

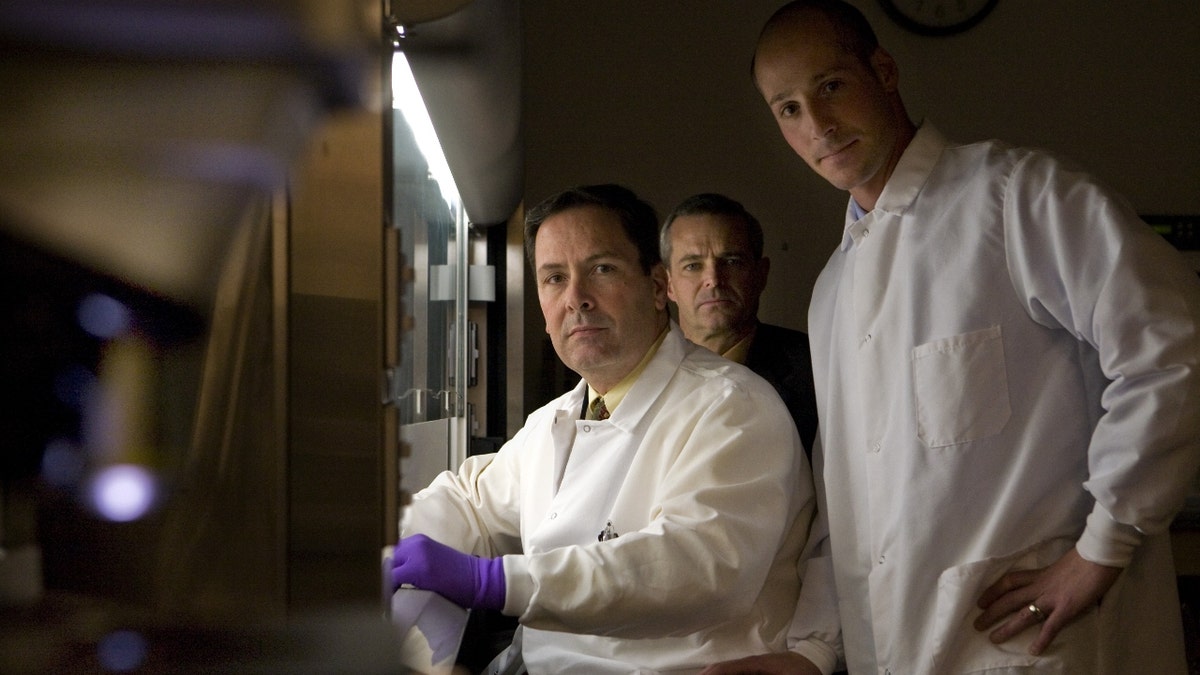

From left, forensic examiner Jason Bannan, Supervisory Special Agent Scott Decker and Supervisory Special Agent Matthew Feinberg, pose for a portrait Oct. 16, 2008 at a lab in Quantico, Va. The three helped solve the anthrax investigation. (Dominic Bracco II/The Washington Post)

Decker's book covers not only his work identifying Ivins' role in the attacks but all the other moving parts that made it possible for the FBI and Justice Department to finally close their investigation in 2010.

The goal of his book, Decker said, is to give some recognition to little-known people who played large roles in uncovering the mystery and saving lives along the way, including Navy Adm. John Eisold, who was the attending physician at the United States Capitol between 1994 and 2009.

A hazardous material worker sprays his colleagues after they finished an anthrax search at Dirksen Senate Office Building Nov. 18, 2001, on Capitol Hill in Washington. (Alex Wong)

U.S. Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle was among one of the victims who received a letter laced with anthrax in 2001. An intern in his office had opened the letter in Daschle's office, causing the powder to float from the envelope to the surrounding room, Decker said.

Capitol Police called Eisold to the scene, and Eisold sent a doctor, his commander and a team of pharmacy technicians to the contaminated office.

"From there, they tested everybody in that building for anthrax. And they came up with about 100 people that had thousands of infectious doses in their nose. And they got that answer within a day, I think. And then they were finding contamination all over Capitol Hill and different buildings. So Admiral Eisold said, ‘This is really a problem,’" Decker recalled.

Members of a biohazard team wait to enter the Hart Senate Office Building Nov. 7, 2001, on Capitol Hill in Washington. (Alex Wong)

Eisold contacted the White House and asked then-President George W. Bush for "a s---load" of antibiotics, protective gear and other materials to prevent any severely adverse reactions to the deadly powder.

The doctor then opened a clinic on Capitol Hill immediately after the attack, and "a couple thousand people came in and got tested" around 7 a.m., Decker said.

Another anthrax discovery on the Hill, this time in the Ford building. U.S. Capitol Attending Physician Dr. John Eisold, left, and Lt. Dan Nichols of the Capitol Police address reporters on the situation. (Bill O'Leary/The Washington Post)

"There was a line outside the door waiting to be tested, and he gave everybody antibiotics before the test results came in, which was against CDC recommendations. The CDC would not treat with antibiotics until they knew you had the disease, but Eisold had been training on biological weapons. And he said, ‘No, you take this for 30 days,’" the former FBI agent said, adding that Eisold probably saved "hundreds, maybe a thousand lives by being aggressive and risking criticism from the CDC."

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Decker added that Eisold "risked his medical career, but … it worked out OK."

Amerithrax investigators interviewed more than 10,000 witnesses on six different continents, executed 80 search warrants and recovered more than 6,000 items of potential evidence over the course of their investigation. The case involved 5,750 grand jury subpoenas and 5,730 environmental samples from 60 site locations.