New study looks at crime rates in Chicago

Study blames 'ACLU effect' for a sharp rise in crime in Chicago. Mike Tobin has more on the study.

The American Civil Liberties Union is to blame for a spike in bloodshed on the troubled streets of Chicago – that is the conclusion of a new study released by the University of Utah.

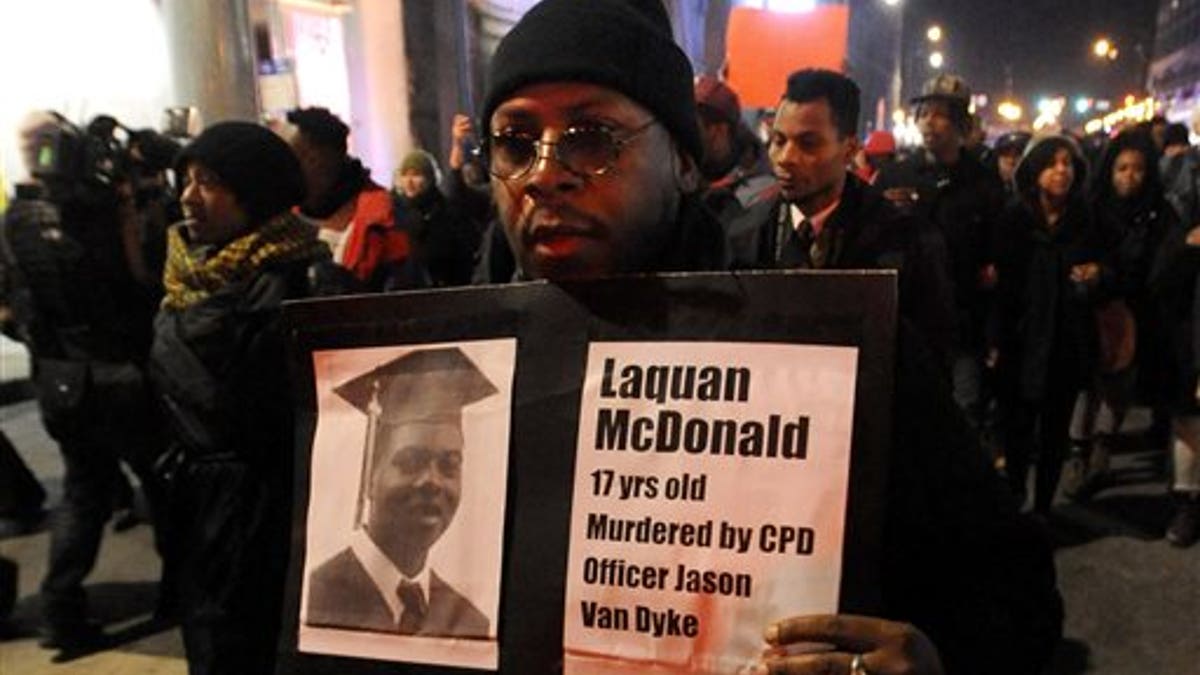

You may remember the shooting of Laquan McDonald. Dramatic video of a Chicago police officer shooting him 16 times was released in 2015. What followed was massive street demonstrations and strained discussion about ethnic profiling by police. Particular attention was paid to police officers stopping young black men and checking them for weapons.

An agreement was reached between the Chicago Police Department and the ACLU and, by 2016, a plan was implemented requiring street cops to fill out contact cards with enhanced detail explaining why individuals were stopped. The cards have 70 entries, some in essay form.

Authors of the study claim the paperwork takes 15 to 20 minutes to complete and has discouraged police from stopping suspicious people and checking them for weapons.

The American Civil Liberties Union is to blame for a spike in bloodshed on the troubled streets of Chicago – that is the conclusion of a new study released by the University of Utah. (REUTERS)

About 100,000 stops were recorded for all of 2016, an 82 percent decrease from 600,000 the previous year. For the same time period, gun violence spiked – 754 people were killed in Chicago, a 58 percent increase from 480 the previous year. The study concludes Chicago endured 1,100 additional shootings from the previous year.

“Criminals on the streets of Chicago became more emboldened to carry guns. The deterrent effect decreased,” said Paul Cassell, one of two authors of the study. “When there are more guns on the street being carried by criminals, the predictable result is an increase in gun-related crimes.”

Dramatic video of a Chicago police officer shooting Chicago teen Laquan McDonald 16 times was released in 2015. What followed was massive street demonstrations and strained discussion about ethnic profiling by police. (AP)

The ACLU argues that the study is flawed, that the authors simply looked at a couple of developments on a timeline and jumped to the conclusion that one caused the other.

“It’s junk science,” said Karen Sheley, a lawyer with the ACLU. “It makes the claim that the math it uses can show one thing caused another. When people who understand social science know the most it can show is correlation that two things might have happened at the same time.”

The ACLU also argues that the report disregards other factors, like anger on the street over the McDonald shooting and the appearance that police falsified their reports following the shooting.

After the police shooting of Chicago teen Laquan McDonald, an agreement was reached between the Chicago Police Department and the ACLU and, by 2016, a plan was implemented requiring street cops to fill out contact cards with enhanced detail explaining why individuals were stopped. Authors of the study claim the paperwork takes 15 to 20 minutes to complete and has discouraged police from stopping suspicious people and checking them for weapons. (2003 Getty Images)

Cassell defends that he did look at factors like anger and mistrust of police, even the opioid epidemic. The study concludes that the anomaly is what he calls the ACLU effect; the administrative burden placed on street cops making them reluctant to police pro-actively. That, he claimed, loosened the scrutiny on criminals and resulted in bloodshed.

“We have a collection of data,” Cassell said, “that comes together to make it clear that causation exists here.”