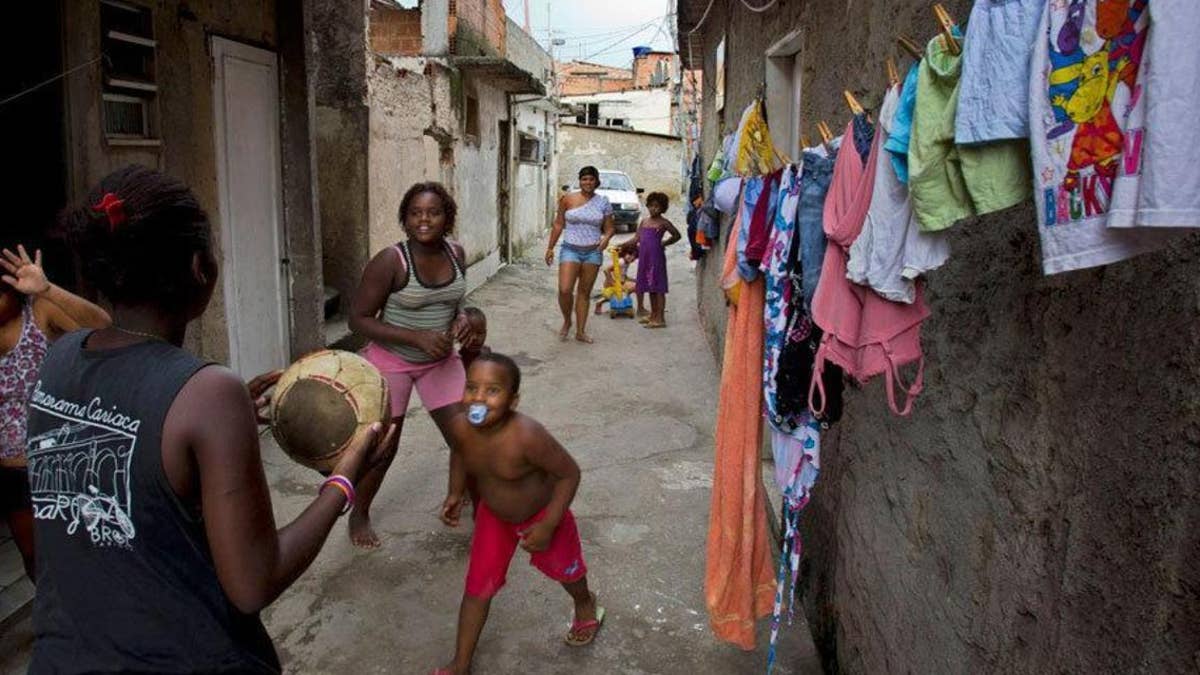

Children play in Favela do Metro shantytown in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. (AP)

It’s a dark form of tourism — voyeuristic excursions to 'Struggle Street' to see how the worse-off live.

It may not be brand new but it may be an inappropriate, booming trend among Western travelers.

More and more tourists are eschewing more conventional tourist attractions and venturing into slums, shantytowns and impoverished villages in developing parts of the world in what’s been dubbed “slum tourism."

About one million tourists visited these sites somewhere in the world in 2014, according to researchers, and recent reports suggest slum tourism continues to grow in popularity.

Dharavi, located in Mumbai, India, is one of the largest slum villages on the Asian continent. (Reuters)

This kind of travel can include gap-year-style trips abroad to volunteer on building projects or teach at a community school in a poverty-stricken village.

But it also includes tours that provide holiday-makers a real sense of the difficult conditions in which people live — turning poverty into a tourist attraction.

An authentic experience?

In Peruvian capital of Lima, where most tourists are drawn to the iconic Incan ruins of Machu Picchu, a small but not insignificant number of travellers are instead seeking out the city’s slums, according to the Associated Press.

And there is no want for tour guides that lead intrepid travellers through the shantytowns that sprung up as people fled conflict in Lima and other cities.

“I want to be just and honest with the visitors who come to get to know my country. Peru is a country full of ‘young towns’,” Haku Tours founder Edwin Rojas said.

Rojas sad his tour agency was the only one to offer “shantytown tours” alongside more conventional historical and culinary tours of Lima.

And about 400 tourists a year visit the region’s slums, at a cost of $60 each. A large part of the appeal is eating with local families — as close to the most authentic Peruvian culinary experience you can get.

“More than a tour, it is an anthropological experience for foreigners to get to know the local people with mutual respect,” said Rojas.

Similar tours in Rio de Janeiro, Mumbai, Nairobi and Johannesburg have accused of exploiting the poor.

In a report by the BBC in 2012, when interest in slum tourism began to take hold, people in the Mumbai informal neighbourhood of Dharavi — which was featured in the film Slumdog Millionaire — weren’t happy about their appeal as a touristic drawcard.

“It doesn’t help me at all,” a trader named Prasad told the BBC.

“We see foreigners several times a week. Sometimes they come and talk to us, some offer us a bit of cash, but we don’t get anything from these tours.”

But Rojas said his tour in Lima was different, as it built strong ties with shantytown community leaders.

“What we do here is more sensitive because when we visit these communities we help the people and get to know the best of them,” he said.

Glossing over real problems

In a piece published on The Conversation this week, University of Leicester lecturer Fabian Frenzel looked at whether slum tourism was doing much good, especially when considered against the backdrop of rising global inequality.

On the one hand, he said, it didn’t.

“We tend to think of tourism primarily as an economic transaction. But slum tourism actually does very little to directly channel money into slums,” Frenzel, a lecturer in the political economy of organisation, said.

“This is because the overall numbers of slum tourists and the amount of money they end up spending when visiting slums is insignificant compared with the resources needed to address global inequality.”

But he acknowledged slum tourism could be a powerful force in bringing visibility to places that would more typically be shunned and hidden away by authorities.

Interest in places such as Dharavi in Mumbai, Johannesburg’s inner-city neighbourhood of Hillbrow and the favelas of Rio de Janeiro are beginning to rival interest in more conventional, nearby tourist attractions.

“Invisibility means that residents of poor neighbourhoods find it difficult to make political claims for decent housing, urban infrastructure and welfare. They are available as cheap labour, but deprived of full social and political rights,” said Frenzel.

“Slum tourism has the power to increase the visibility of poor neighbourhoods, which can in turn give residents more social and political recognition.”

But, Frenzel noted “visibility can’t fix everything.

“It can be highly selective and misleading, dark and voyeuristic or overly positive while glossing over real problems."

“To live up to this potential, we need to reconsider what is meant by tourism, and rethink what it means to be tourists.”