Fox News Flash top headlines for July 2

Fox News Flash top headlines for July 2 are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com

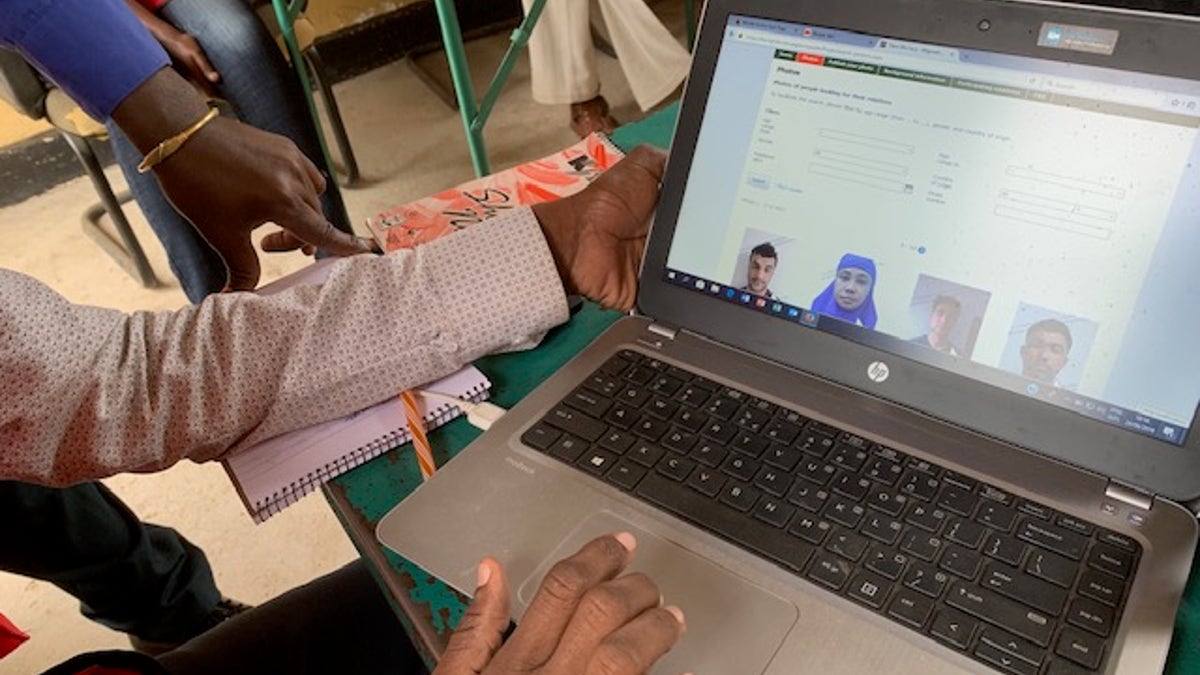

KAKUMA, Kenya – In a small Kenyan Red Cross office in the heart of the vast and parched Kakuma Refugee camp, two young men intently scroll through pages and pages of photographs of refugees and displaced persons, uttering not a word as they examine each and every image that glares back.

They are just two of millions who are every day searching and waiting for the sign of a familiar face; that perhaps a loved one is alive and looking for them somewhere among the diaspora of war victims and survivors who have scattered to unknown corners of the earth.

But as the world becomes ever rifer with refugees, internal displacement and conflict, much of the work of humanitarian actors now centers on trying to locate and unite loved ones who have scattered to various corners of the earth amid the chaos of a crisis. Indeed, the accelerated rise of new technologies has dramatically altered the humanitarian sector and the fundamental quest of locating the missing and reuniting families in what is officially known as “Restoring Family Links” (RFL).

“With suggestions from the communities we serve, the Red Cross Movement is looking to further leverage on technology in order to improve our work and restoring contact between separated families,” Konrad Bar, Interim Protection Coordinator of the ICRC Nairobi, told Fox News.

SHUNNED CONGOLESE REFUGEE ON RAISING A SON BORN OUT OF RAPE: THE BABY HAD A RIGHT TO LIVE

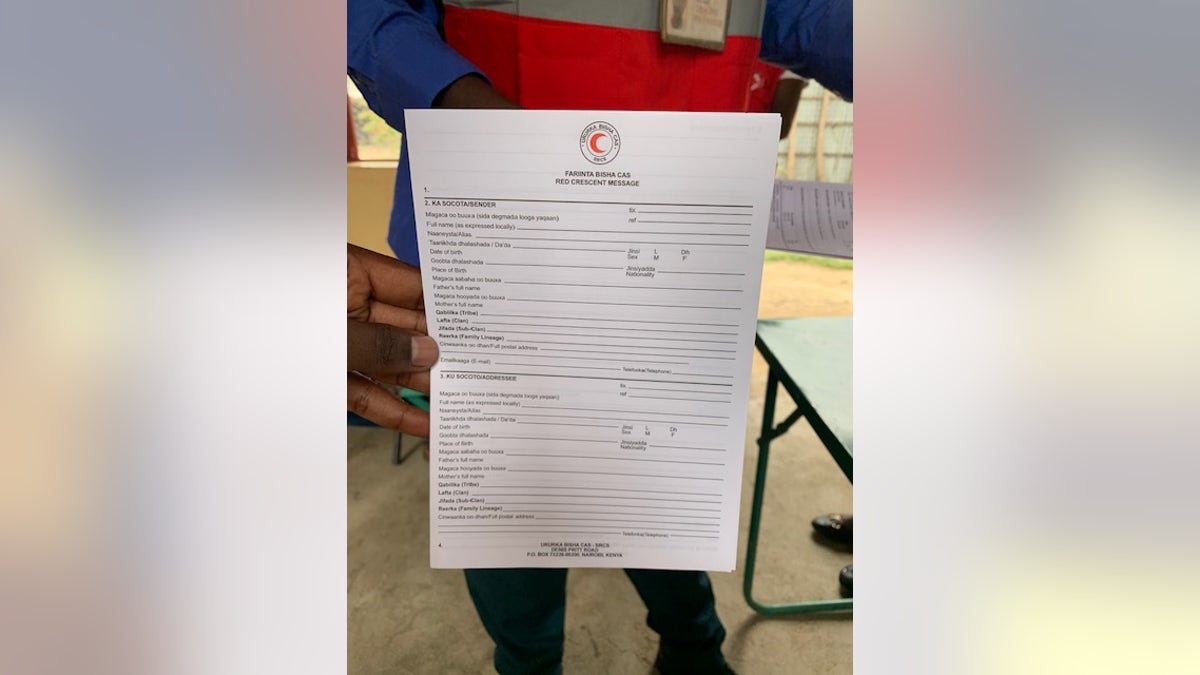

Yet given that most who have fled war still live in extreme poverty or with little access to the advent of cutting-edge telecommunications, RFL requires a technological toolbox of both new and old. The staple of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) “Trace the Face” program is an online directory – a kind of Google for refugees and the internally displaced – where profiles are set up for both those missing and those seeking the missing, specifying which relative they are looking for, after filling out forms with Red Cross staff and volunteers.

Searching for missing loved ones inside a small Kenyan Red Cross office inside the sprawling Kakuma camp (Fox News/Hollie McKay)

No personal details are made public, with just photographs used. Refugees who aren’t able to access any type of internet themselves are also able to visit offices set up in many camps – the Kenyan Red Cross operates five in Kakuma alone – to search the databases there.

As it stands in Kakuma – which is home to more than 150,000 refugees mostly from different regions in Africa – there are 45 enquirers, which refers to profiles of people who are looking for family members, and 43 missing which means profiles set up for people who are being searched for by relatives. But globally, the website has some 14,648 enquirers and 14, 219 missing since it was launched in 2013.

In addition to the online directory, photographs are also printed in booklets that are then distributed through refugee populations like a sought-after magazine, a traditional but still important function for reunification across the world. And if a connection is made, the Red Cross workers make verifications before forging the connection.

Yet as is the nature of conflict; restoring family links can come with both an uplifting and painful ending when it comes to determining the ill fate of lost loved ones.

For one, 50-year-old Shamsa – a refugee who fled Somalia more than a decade ago after her husband was murdered by militiamen – waited for months in angst after her brother Yassin decided to leave the camp and make his way through South Sudan and on to Libya in 2016 in a quest to make money to send back to the languishing family in Kakuma.

Shamsa and Red Cross volunteer, Abdullah Sheikh (Fox News/Hollie McKay)

The expansive UNHCR Kakuma Refugee Camp lies in northwestern Kenya, some 60 miles from the South Sudan border, in what has long been deemed one of the poorest parts of the country. Since 1992, the camp has hosted thousands upon thousands of war victims – now bursting beyond capacity with more than 180,000 crammed inside the semi-arid desert encampment.

Dotted with thatched roof huts and mud dwellings, Kakuma camp is an abode of both freedom and imprisonment for those inside – freedom from the unrest and violence of the homelands in which they were forced to flee, but imprisonment in the sense that most are unable to work outside the grounds and are not able to easily travel without obtaining official permission, making external employment deeply challenging.

“My brother was communicating, and when he got to Libya he called and said he was really sick and they had broken his leg. He said some rebels had captured him in Libya and demanded he give them money but he had none,” Shamsa wearily recalled. “Then for a long time, I heard nothing.”

The proliferation of those seeking refuge in Europe had ignited months earlier in the late summer of 2015 when German Chancellor Angela Merkel issued directives mostly to support Syrians fleeing their war-ravaged homeland, in what became a controversial “open door refugee policy” earning international praise for compassion but also condemnation for hampering EU security.

FILE -- In this June 2, 2016 file photo, the body of a migrant lays on the beach, one of more than 100 bodies pulled from the Mediterranean Sea after a smuggling boat carrying mainly African migrants sank, near the western city of Zwara, Libya. (APTV via AP, File) (The Associated Press)

It also meant that many from far and wide, far beyond Syrian borders, also left camps for a shot at the European dream – the route for many Africans requiring a dangerous stop over to board a smugglers’ boat in Libya. It is estimated that over 6,000 migrants at present have been stuffed into Libyan detention facilities, often at the mercy of forced militia recruitment and severe torture.

Suddenly one morning, Shamsa received an anonymous call – believed to be from a fellow detainee – informing her that her Uncle had died as a result of torture in captivity and had been buried. Two years on, Shamsa still does not know where her brother was buried and her tireless calls to that number no longer go through.

NIGERIA’S CHRISTIAN COMMUNITY SLOWLY BEING ERASED AS MILITANTS STEP UP VICIOUS KILLINGS, KIDNAPPINGS

And much to her horror, early last year Shamsa’s then 24-year-old son too decided he needed to leave to find work as the eldest man of the house – also with the dangerous aspiration to cross the Mediterranean and move on to Europe.

“He was communicating and sending money for a couple of months – and then nothing. There was no communication, no news, no one knew where he was. I went to the Red Cross to make a request to find him,” Shamsa lamented. “I worried a lot because my brother had died and I expected my son had passed away too.”

But then, after more than a year of silence, the son’s friend happened to find a video of his mom in Kakuma searching for him on Facebook and soon a family connection and phone call was established. He didn’t make it across the seas to Europe but is safe in another African country.

The coveted moment of “reunification” happens in a multitude of ways. First up, is the trusty mobile – or satellite in very remote regions – phone, as the majority of refugees in the East Africa area don’t have the funds to own phones or calling cards of their own.

Filling out forms to locate the missing who may have attempted to migrate to Europe. (Fox News/Hollie McKay)

From January of this year, phone calls were also facilitated at the camp office and for the first six months of 2019, some 21,660 telephone chats were clocked up, making it an average of 3,936 per month between displaced family members. Individuals are allowed one phone call a month, for a maximum of two minutes.

Some even have access to video calls.

But in many remote regions wracked by calamity, internet, and even mobile phone use is scarce – making it pivotal new technological advancements are paired and even take a backseat to legacy methods of communication.

Relatives are thus encouraged to communicate via postcards – which are monitored by Red Cross volunteers to ensure that they are focused on family affairs and not political or potentially inflammatory content – which are then sent to other partner offices across the globe.

Scrolling through the directory to restore family links. (Fox News/Hollie McKay)

And radio too remains a vital player.

“The names on the directory are read out on BBC Somalia, who gives us some airtime,” explained Abdullah Sheikh, a volunteer in the Kenyan Red Cross office in Kakuma. “Friday is resting day there so it’s especially important, people tune in to listen for a familiar name.”

Kakuma Refugee Camp in north-west Kenya (Fox News/Hollie McKay)

But from the perspective of Shamsa – who noted that not a day passes by that she doesn’t pine for her brother and for her son to come back to Kakuma – encouraging families to stay together wherever possible are her words of wisdom.

“Some who put a post on Facebook about how great it all is and young people see that and don’t see the downside, they just see the hope and see great things even if they aren’t true,” she added. “I say don’t go, my brother passed away trying. Stay here.”