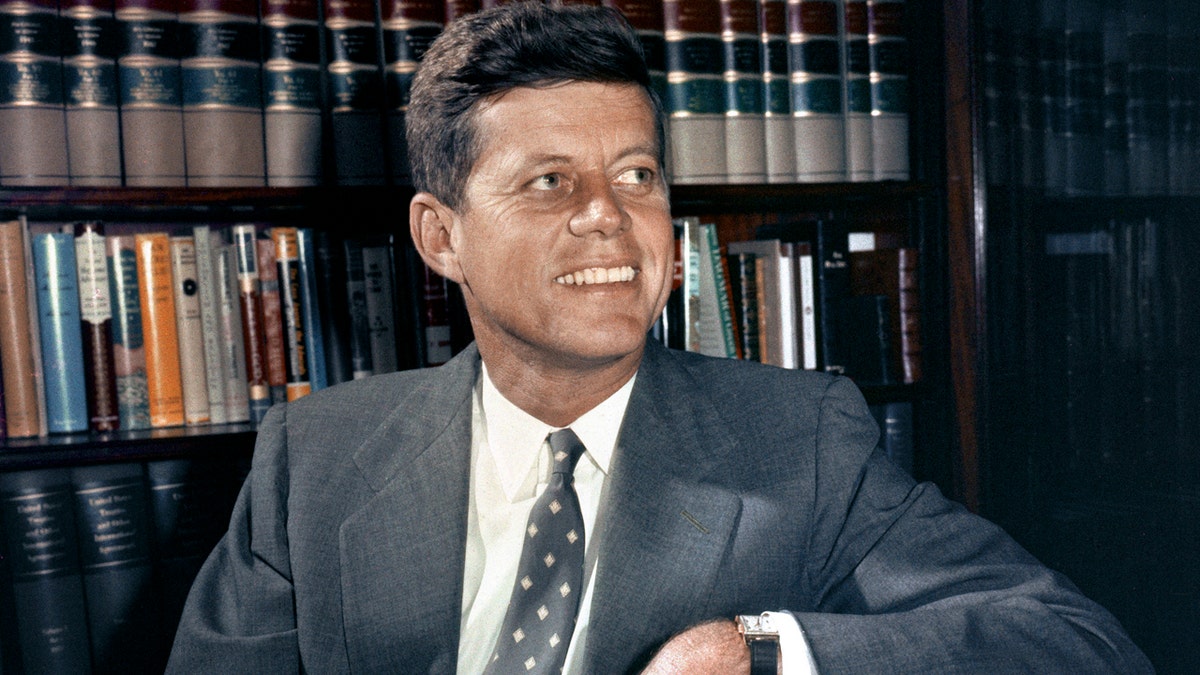

CNN was slammed for hypocrisy over the weekend when the network glorified President John F. Kennedy’s many infidelities after spending significant coverage painting President Trump as a monster for an alleged affair that occurred prior to his political career. (AP)

NASA entered the popular imagination when JFK gave his famous "We choose to go to the Moon" speech on Sept. 12, 1962. At the time, the agency was just four years old and charged with developing all US civil aerospace research and development.

Mission 1 was the first US satellite, Explorer 1, which took off from Cape Canaveral in 1958. Scientific equipment onboard discovered charged particles trapped in space by Earth's magnetic field, now known as the Van Allen Belts. In the 60 years since, NASA has carried out 186 crewed and robotic missions.

Its vision was and remains: "We reach for new heights and reveal the unknown for the benefit of humankind." In 2018, that means "preparing to take humankind farther than ever before, as it helps to foster a robust commercial space economy near Earth, and pioneers further human and robotic exploration as we venture into deep space."

Ahead of NASA's 60th anniversary celebrations, I spoke with Dr. Charles Norton, NASA SMD Assistant Deputy Associate Administrator for Small Spacecraft Programs, and Dr. Anne Marinan, Systems Engineer for NASA CubeSat missions.

More From PCmag

When and why did you both join NASA?

Dr. Anne Marinan: I was a NASA Fellow all through grad school, and I did research at JPL [the Jet Propulsion Laboratory]and NASA Ames Research Center while completing a PhD in Aero/Astro at MIT. I came to JPL as a full-time employee in 2016. I've always been interested in space exploration and wanted to be part of NASA's overall mission. There's nothing else like it. I talk to satellites on a daily basis, we're making discoveries all the time about Earth and space. It's a very cool thing to do.

Dr. Charles Norton: I've been with NASA over 20 years now. After completing my PhD in Computer Science from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, where I was a NASA Fellow, and after a postdoctoral appointment—through the National Academy of Sciences at JPL—I formally joined the lab in 1988 to perform work in high performance computational science.

Dr. Norton, you recently switched to the 'front office' and commute between NASA HQ and JPL as the new Assistant Deputy Associate Administrator for Programs, Small Spacecraft Missions at NASA Science Mission Directorate.

CN: Yes, this is a new role which focuses on establishing agency coordination within the science, space, technology and human exploration mission directorates. My purpose is to provide strategy and policy advice to the associate administrators on the role that small spacecraft can contribute to NASA's objectives. Drawing on the scientific benefits and, on a more practical level, establishing throughout the agency where we're going with small spacecraft and how they can contribute to a balanced program of space exploration.

What is the role for small spacecraft for NASA moving forwards?

CN: They allow for rapid development, and are a cost-effective way to enable new types of science and observations. Small satellites and CubeSats can be used for constellation missions to increase our orbital coverage and rapid revisit capabilities, for sustained scientific, exploration and technology missions in space. Given that you can deploy so many of them at a time, it gives us greater resiliency against potential failures.

How long can they stay in orbit?

CN: Their useful lifetime is increasing all the time. Some of our small spacecraft have been up there for over 10 years; [it] depends on the orbit.

Dr. Marinan, can you briefly explain your current assignment on the MarCO mission to Mars?

AM: Right now I'm spending most of my time on the first deep space small satellite flight project—MarCO—the first twin Cubesat small satellites that launched on May 5, 2018 with the InSight lander, heading to Mars. The lander is due to land in November, on the planet, and MarCO is a bit over halfway to Mars. They're on their own trajectory right now and will flyby around the time InSight lands. Its purpose is a technical demonstration, to show we can bring our own relay capability when a lander goes to Mars or another planet and provide transmission back to Earth directly.

Are you using robots in your work today?

AM: Yes! Essentially all the spacecraft we build are robots. We do a lot of telling them exactly what we need them to do, but they all have an onboard processor and some level of autonomy and sensor feedback system.

Our eyes and ears in space?

AM: Right, these small satellites are metal and silicon "human amplifiers," an extension of us out there. We're putting these eyes, ears, and sensors into space, and are then able to take radio signals and light signals and translate them into physical meaning.

Dr. Norton, do you recall your first satellite launch?

CN: I'll never forget the first mission, when I was responsible for the delivery of a CubeSat flight system. It was in October 2011, the M-Cubed/COVE mission, developed in partnership between the University of Michigan and JPL, to validate a new real-time high-data rate instrument signal processing system to advance cloud and aerosol science. It was a ride share mission with NASA's NPP mission from Vandenberg Air Force Base, but I couldn't be there at the launch site, as I needed to be in San Diego [300 miles south]. However, I remember looking north, over the Pacific Ocean, at 3 a.m., as it took off, and there it was—the full arc of the rocket launch.

What did it feel like, knowing your satellites were on that rocket?

CN: It was an amazing sight and a wonderful sense of accomplishment for our entire team.

Is M-Cubed/COVE still up there in space?

CN: Yes and no. The original M-Cubed/COVE spacecraft suffered an on-orbit failure, but the mission was re-flown only two years later at significantly reduced cost. This represents one of the great advantages of these small spacecraft. You can track it by launching the NASA's Eyes on the Earth System app here.

Dr. Marinan, can you describe what it's like communicating with something out in deep space?

AM: Strangely, it's an unassuming office room that we use for day-to-day operations on MarCO [Laughs]. Just walking by it looks like anyone could be in there just surfing the internet, but you're not—you're looking at plots on a screen that represent data and information that traveled over 20 million miles to get to you. It's mind-blowing.

And surreal?

AM: Completely. I'm sitting there, on a headset, communicating with the Deep Space Network, ingesting and analyzing data from out there in the universe.

With MarCO heading to Mars, it's clear small satellites are a vital part of future robotic—then human—exploration.

CN: Indeed. We focus primarily on free-flying scientific spacecraft today, although there is an interest in using them as inspectors of platforms that would contribute to lunar and human exploration objectives in the near, medium and long term future.

Finally, NASA@60 is a huge achievement. Can you both explain the agency's significance as we move beyond being a single planet species?

AM: It's amazing to see how far NASA has come—especially in areas outside of space exploration that most people don't typically think of: Earth science, quantum computing, robotics, aeronautics, and more. Working at NASA is the epitome of working inside a dream team. Everyone here loves what they do and we're working collectively to do something really good for the future of humanity.

CN: It's a great question. I've had a long-term personal connection to NASA as my father, who sadly died not long after I was born, worked on the Lunar Module for the Apollo Mission, while at Grumman Aerospace [now Northrop Grumman]. In my view, exploration is fundamental to human nature—not just on an intellectual level, but emotional too. It's incredible to think how far we've come over the past 60 years.

This article originally appeared on PCMag.com.