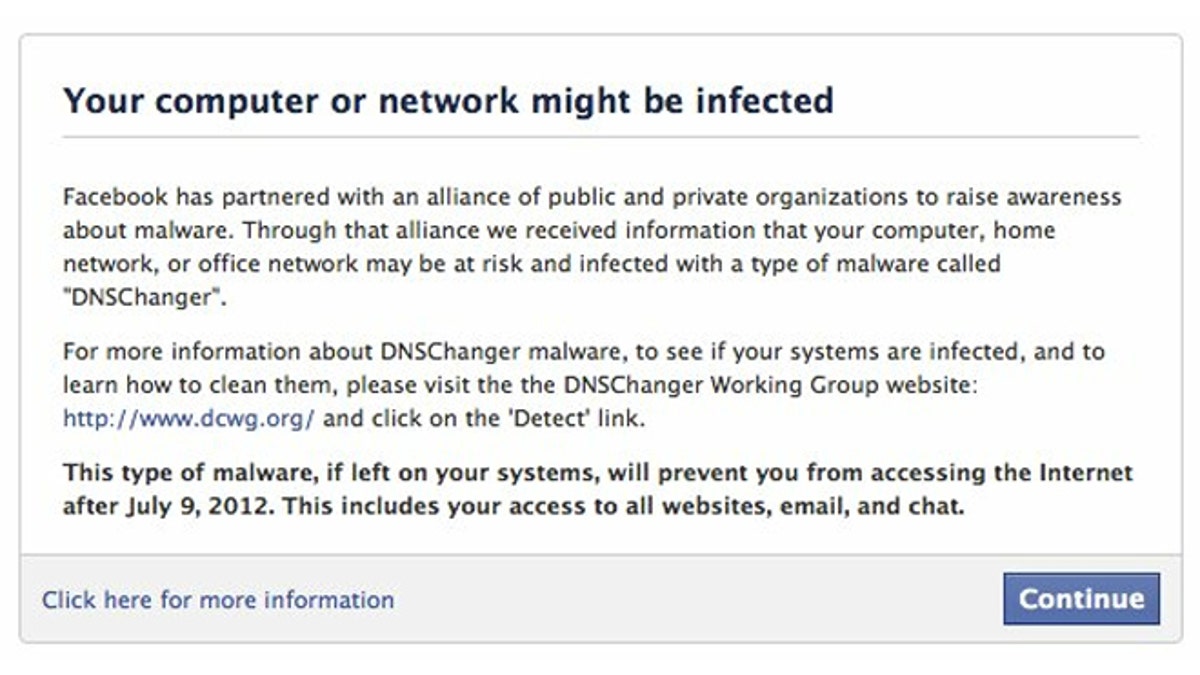

Facebook plans to aid an FBI awareness campaign with these warnings, which should crop up on the Facebook pages of more than half a million infected web browsers. (Facebook)

WASHINGTON – Facebook announced Tuesday that it had joined a consortium of other companies and security experts to help alert hundreds of thousands of websurfers of a computer infection called DNSChanger that may knock their computers off the Internet this summer.

Unknown to most of them, their problem began when international hackers ran an online advertising scam to take control of infected computers around the world. In a highly unusual response, the FBI set up a safety net months ago using government computers to prevent Internet disruptions for those infected users. But that system will be shut down July 9 -- killing connections for those people.

The FBI has run an impressive campaign for months, encouraging people to visit a website that will inform them whether they're infected and explain how to fix the problem. After July 9, infected users won't be able to connect to the Internet.

[sidebar]

Infected Facebook users will now be treated to a special message when visiting the social network that informing them of their potential risk as well as helping them clean it up.

"Facebook's Product Security Team is working constantly to protect users from malicious content and malware like viruses, trojans, and worms," Facebook wrote in a blog post Tuesday, June 4.

"As a result of our work with the DNSChanger Working Group, Facebook is now able to notify users likely infected with DNSChanger malware and direct them to instructions on how to clean their computer or networks."

Facebook followed in the footsteps of Google, who on May 22, announced that it would throw its weight into the awareness campaign, rolling out alerts to users via a special message that will appear at the top of the Google search results page for users with affected computers.

“We believe directly messaging affected users on a trusted site and in their preferred language will produce the best possible results,” wrote Google security engineer Damian Menscher in a post on the company’s security blog.

“If more devices are cleaned and steps are taken to better secure the machines against further abuse, the notification effort will be well worth it,” he wrote.

The challenge, and the reason for the awareness campaigns: Most victims don't even know their computers have been infected, although the malicious software probably has slowed their web surfing and disabled their antivirus software, making their machines more vulnerable to other problems.

Last November, when the FBI and other authorities were preparing to take down a hacker ring that had been running an Internet ad scam on a massive network of infected computers, the agency realized this may become an issue.

"We started to realize that we might have a little bit of a problem on our hands because ... if we just pulled the plug on their criminal infrastructure and threw everybody in jail, the victims of this were going to be without Internet service," said Tom Grasso, an FBI supervisory special agent. "The average user would open up Internet Explorer and get `page not found' and think the Internet is broken."

On the night of the arrests, the agency brought in Paul Vixie, chairman and founder of Internet Systems Consortium, to install two Internet servers to take the place of the truckload of impounded rogue servers that infected computers were using. Federal officials planned to keep their servers online until March, giving everyone opportunity to clean their computers.

But it wasn't enough time.

A federal judge in New York extended the deadline until July.

Now, said Grasso, "the full court press is on to get people to address this problem." And it's up to computer users to check their PCs.

[pullquote]

This is what happened:

Hackers infected a network of probably more than 570,000 computers worldwide. They took advantage of vulnerabilities in the Microsoft Windows operating system to install malicious software on the victim computers. This turned off antivirus updates and changed the way the computers reconcile website addresses behind the scenes on the Internet's domain name system.

The DNS system is a network of servers that translates a web address -- such as http://www.foxnews.com -- into the numerical addresses that computers use. Victim computers were reprogrammed to use rogue DNS servers owned by the attackers. This allowed the attackers to redirect computers to fraudulent versions of any website.

The hackers earned profits from advertisements that appeared on websites that victims were tricked into visiting. The scam netted the hackers at least $14 million, according to the FBI. It also made thousands of computers reliant on the rogue servers for their Internet browsing.

When the FBI and others arrested six Estonians last November, the agency replaced the rogue servers with Vixie's clean ones. Installing and running the two substitute servers for eight months is costing the federal government about $87,000.

The number of victims is hard to pinpoint, but the FBI believes that on the day of the arrests, at least 568,000 unique Internet addresses were using the rogue servers. Five months later, FBI estimates that the number is down to at least 360,000. The U.S. has the most, about 85,000, federal authorities said. Other countries with more than 20,000 each include Italy, India, England and Germany. Smaller numbers are online in Spain, France, Canada, China and Mexico.

Vixie said most of the victims are probably individual home users, rather than corporations that have technology staffs who routinely check the computers.

FBI officials said they organized an unusual system to avoid any appearance of government intrusion into the Internet or private computers. And while this is the first time the FBI used it, it won't be the last.

"This is the future of what we will be doing," said Eric Strom, a unit chief in the FBI's Cyber Division. "Until there is a change in legal system, both inside and outside the United States, to get up to speed with the cyber problem, we will have to go down these paths, trail-blazing if you will, on these types of investigations."

Now, he said, every time the agency gets near the end of a cyber case, "we get to the point where we say, how are we going to do this, how are we going to clean the system" without creating a bigger mess than before.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.