‘Aging’ 9-1-1 systems slowly begin to see video and text upgrades

Emergency communications centers are beginning to introduce video livestreaming and texting options amidst wake of criticism over the country's aging 911 systems.

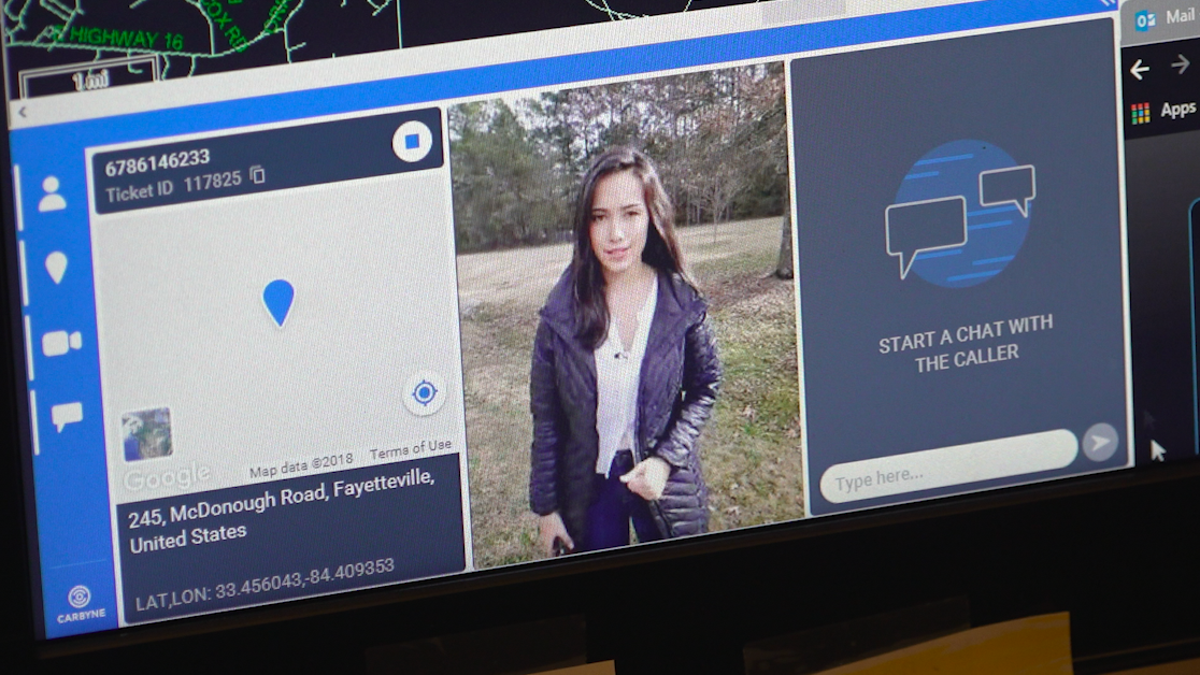

FAYETTEVILLE, Ga. — “Is that the patient right there?” asked Camri Copeland, a communications officer. Right there. Copeland could actually see the scene of a car crash from an emergency communications center in Fayette County, Ga. through one of the nation’s first video livestreaming 911 calls.

The video helped pinpoint exactly where the vehicles were, as first responders headed to the scene.

“You get a better understanding of what’s going on out there,” Copeland, less than two years into the job, told Fox News. “You use your eyes and ears, so it’s just the benefit of being able to see what [the 911 callers] probably don’t see.”

International company, Carbyne, brought the technology to the U.S. earlier this year. It has rolled out video and texting options at six public safety answering points (PSAPs) so far, with three more on the way.

The technology comes amid a wake of criticism over the country's aging 911 systems, which celebrated its 50th anniversary this year.

The past two decades, as wireless technology has rapidly advanced, experts have questioned why America's most crucial communication system continues to struggle to keep pace.

Apps like Uber and Facebook can locate mobile users immediately, but many 911 centers still have a tough time finding wireless callers who don't know their location -- and, in emergencies, just seconds can make a difference between life and death.

Fox's Emilie Ikeda tests out Fayette County's video 911 call, appearing on a call-taker's screen.

“Right now, the communications habits and preferences of America are changing so quickly away from voice calls,” said Dan Henry, director of government affairs with the National Emergency Number Association. “It’s really crucial that 911 keeps up with those advances or else it risks becoming irrelevant.”

Local governments pay for 911 centers, which has led to a “patchwork implementation” of technology, according to Henry. So while one county may have the latest equipment -- with text and video capabilities -- a nearby county or municipality could have aging technology that impedes its ability to immediately locate a caller.

About 80 percent of 911 calls are made from cell phones.

A bill currently before Congress – that will likely be reintroduced next session – is aimed at accelerating upgrades nationwide with additional federal grants.

A recent report to Congress revealed the estimated cost of NG911 deployment, which would transition PSAPs to an Internet Protocol-based 911 system, allowing for a smoother flow of digital information, is between $9.5 and 12.7 billion.

The problem is that, because of outdated technology, a 911 call from a wireless phone does not provide the 911 operator with the precise location -- the call is pinged to a cell phone tower, which gives the call center a vague sense of where the caller is.

Brian Fontes, CEO of the National Emergency Number Association, a group that promotes technological improvements in 911 systems nationwide, said that the inability to keep pace with fast-changing technology is hurting everyone.

“[A] First-first responder is in a world of hurt,” Fontes said. “Much of 911 today is stuck in last-century technology...Could you imagine yourself talking only in a voice channel?”

Fire personnel in Fayette County, Ga. ready a truck to respond to emergencies.

Less than one-third of PSAPs offer text-to-911 as an option and even less offer video, according to the FCC.

But there are some municipalities on the cutting edge of technology.

When residents dial 911 in Fayette County, communications officers can send a link to the caller’s phone, which enables video live streaming or texting.

Interim director of Fayette County 911, Kayte Vogt, called it a comfort factor. “They realize that I know exactly where they are,” she said.

Residents can also go through Carbyne’s app for video, text and improved location detection capabilities.

Melissa Alterio works north of Atlanta, where residents can text 911 directly. She heralded the technology, pointing to a case where a call-taker was able to give medical advice via text to someone who was having trouble breathing, thus didn’t want to talk on the phone.

While Alterio sees how text and video can provide call-takers more immediate information, she questions if there’s such a thing as providing too much information.

“We experience trauma just talking to somebody on the phone through their worst crisis,” Alterio told Fox News. “But once we start seeing graphic images…we’re very concerned about the trauma that that’s going to have on the 911 professionals.”

It’s something even Carbyne acknowledges.

“We recognize that video has the potential to do amazing things, but it also risks adding trauma for call-takers,” Amir Elichai, founder of Carbyne, wrote in an email to Fox News.

Elichai, a former Israeli Army officer, said this area of concern still needs to be researched. But, in the meantime, the technology provides the option for the communications officer to turn off the video.

For Copeland, who comes from a family in the police force, she said it is all part of what she signed up for. “It’s kind of a ‘do your job’ situation.”