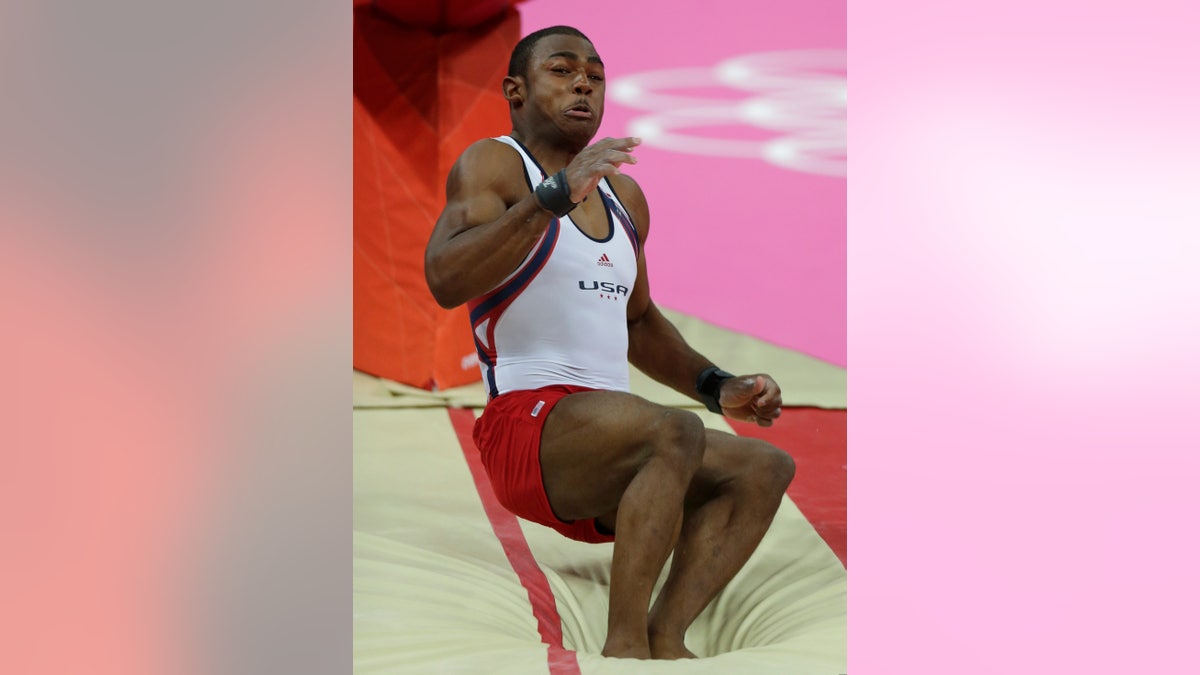

U.S. gymnast John Orozco botches his dismount on the vault during the Artistic Gymnastic men's team final at the 2012 Summer Olympics, Monday, July 30, 2012, in London. (AP Photo/Gregory Bull) (AP2012)

John Orozco knew from an early age he never quite fit in.

Not at school, where his classmates would tease the soft-spoken Orozco for his shyness. Not in the gritty Bronx neighborhood where he grew up, the one his parents Willie and Damaris did their best to protect their five children from.

The only place Orozco felt really alive, the only place he felt at home, was the gym.

No, not the one with weights and treadmills and basketball hoops, the one with the vault and the high bar and the foam pit. The one that invades American living rooms every four years at the Olympics.

Orozco got sucked in long ago. Sitting transfixed watching American Paul Hamm grab the gold in Athens eight years ago, Orozco envisioned the day he would walk onto the floor under the five Olympic rings in a Team USA uniform.

He'll do that again Wednesday in the men's all-around final, the culmination of years of hard work and sacrifice by Orozco, his family and the coaches and clubs that supported him from rambunctious youngster into ambitious prodigy.

And the thoughtful 19-year-old understands there's more at stake than just personal glory.

The dark-skinned son of Puerto Rican parents knows he -- as well as Cuban-born American Danell Leyva and women's rising star Gabby Douglas, who is black -- are beacons.

"I hope I can be a role model and a good inspiration for kids that have been in my situation," Orozco said.

Since Ron Galimore broke the color barrier when he made the 1980 U.S. Olympic team that ended up boycotting the Moscow Games, there have been a handful of minority American stars, most notably four-time Olympic medalist Dominique Dawes.

Yet Orozco, Leyva and Douglas are at the front of a new wave that could render the notion obsolete that elite gymnastics are for mostly affluent, predominantly white suburban kids.

They're hardly alone at the top as it is. Elizabeth Price and Kennedy Baker, who are both black, made the senior national team, with Price serving as an Olympic alternate.

Josh Dixon, whose is of Asian and African-America descent, made the men's senior national team. The program's two most promising juniors -- Donnell Whittenberburg and Marvin Kimble -- are both black.

If Leyva, who topped qualifying, Orozco or Douglas stand atop the medal podium after their respective all-arounds this week, the wave could turn into a flood. Orozco came in fourth behind Leyva during preliminaries, while Douglas was third.

"I think times have changed," said Raj Bhavsar, a member of the 2008 U.S. men's Olympic gymnastic team who is Indian-American. "I don't think it has anything to do with being more inclusive or a change in the political side of the support. I just think these gymnasts, regardless of background, happen to be the best."

USA Gymnastics president Steve Penny says there's been a movement at the club level to embrace diversity.

"The gymnastics community really does take ownership of talent," Penny said. "When they see kids that really want to do the sport, they'll go above and beyond to keep them in the sport. I think John Orozco is an example of that."

Orozco's potential became readily apparent after taking up the sport as a young child. He quickly outgrew the small gym in Manhattan where he began competing and began training at World Gym in leafy Chappaqua, just north of the city.

The 45-minute commute each way could be soul-deadening. Yet Orozco never missed a day. Neither did his parents, who did what they could to meet the considerable financial burden that comes with trying to help their youngest child pursue his dreams.

When there were birthday parties at the gym, Willie and Damaris would serve as crowd control while their son did tricks to entertain the other kids. When a new floor needed to be installed, Willie joined the crew that put it in.

Despite working alongside well-heeled kids, Orozco insists he never felt out of place. The only real instance of racism he encountered came during a free camp at West Point.

Orozco arrived giddy at the thought of spending a few days away from the city. Two days in, he woke up and told his parents he didn't want to go.

"He went to play with this kid and the kid told him, 'Get away from me. My mom said black people carry diseases,"' Willie Orozco said. "It was sad. It really was sad."

It was also rare.

Rather than racism, the Orozcos found a sense of community, where John became "John from the gym." As Orozco rose through the ranks, so did the cost. The high-profile meets kept getting farther and farther away.

Yet the folks at World Gym understood the singular talent they had on their hands. Anonymous donors would chip in when they could. Owner John Sabalja would sometimes work out a barter system to make sure the Orozcos weren't overwhelmed.

"John's the kind of kid you get one in a hundred lifetimes," said Carl Schrade, who coached Orozco until he reached middle school.

Maybe to Schrade, but not to Orozco.

He knows there are others out there like him, minorities whose curiosity for the sport needs to be nurtured. At some point he would like to open a gym in his old neighborhood, a place for kids looking for a place to fit in to call home.

"Maybe one day they'll become a real club gym and be competing and everything," Orozco said. "That's my dream. And I want to start opening up increasingly. Not just from the Bronx. Expanding to places like Brooklyn, and then out to different cities. That would be really cool."

It's a dream that could come closer to reality if Orozco continues his rise. The U.S. men struggled in the team final on Monday, Orozco shouldering a heavy part of the blame after uncharacteristic miscues on both pommel horse and vault.

Though it's unlikely either he or Leyva will have a chance of supplanting three-time defending world champion Kohei Uchimura, they'll be in the mix for a medal.

They'll also be on TV, their faces -- ones of color -- reflecting a change in a program that is becoming as diverse as the country it represents.