Black vs White: Historic college basketball game kept secret

‘The Secret Game’ tells the story of a 1944 basketball game played at the height of segregation in the South

Long before this year's edition of March Madness tipped off, two teams squared off in a nearly-empty gym, with no reporters and no scorecards, for a game whose historical and social significance may dwarf that of any basketball contest played before or since.

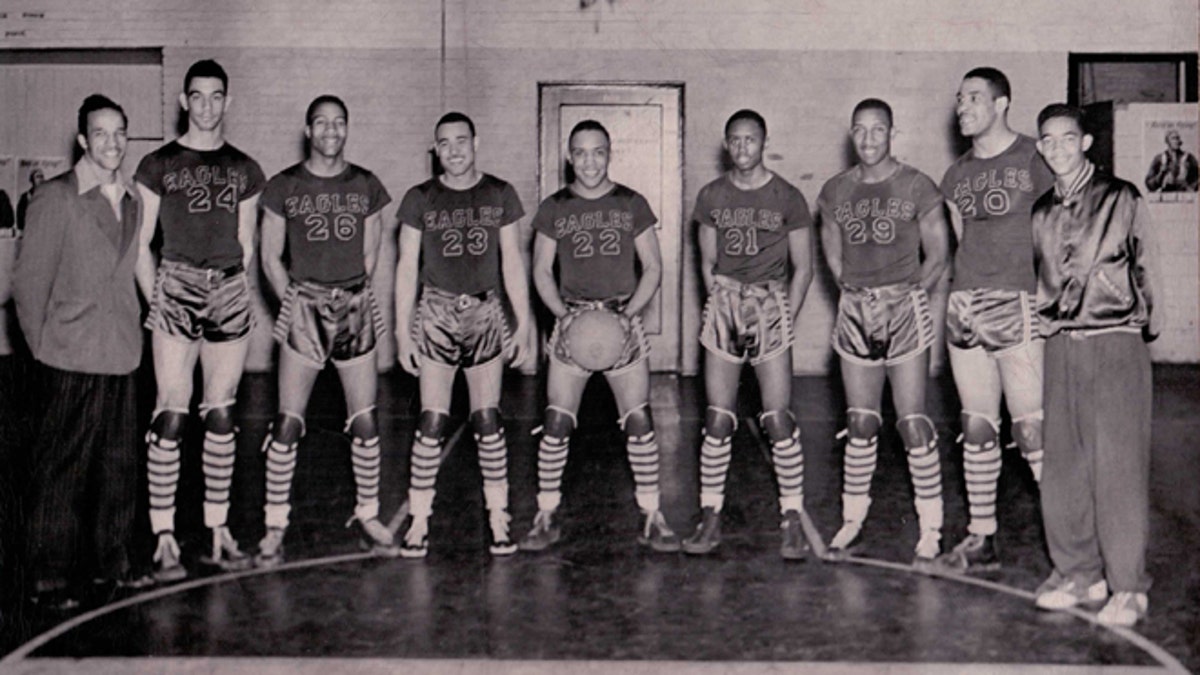

It was March 19, 1944, and a fast-breaking team called the Eagles from the North Carolina College for Negroes, today called North Carolina Central University, took on the Duke University Medical School's team, which was comprised of former star athletes from across the country. The contest, forever marked in hardwood lore as "The Secret Game," marked the first time black and white college students faced off on the same court in the sport James Naismith had invented some 53 years earlier.

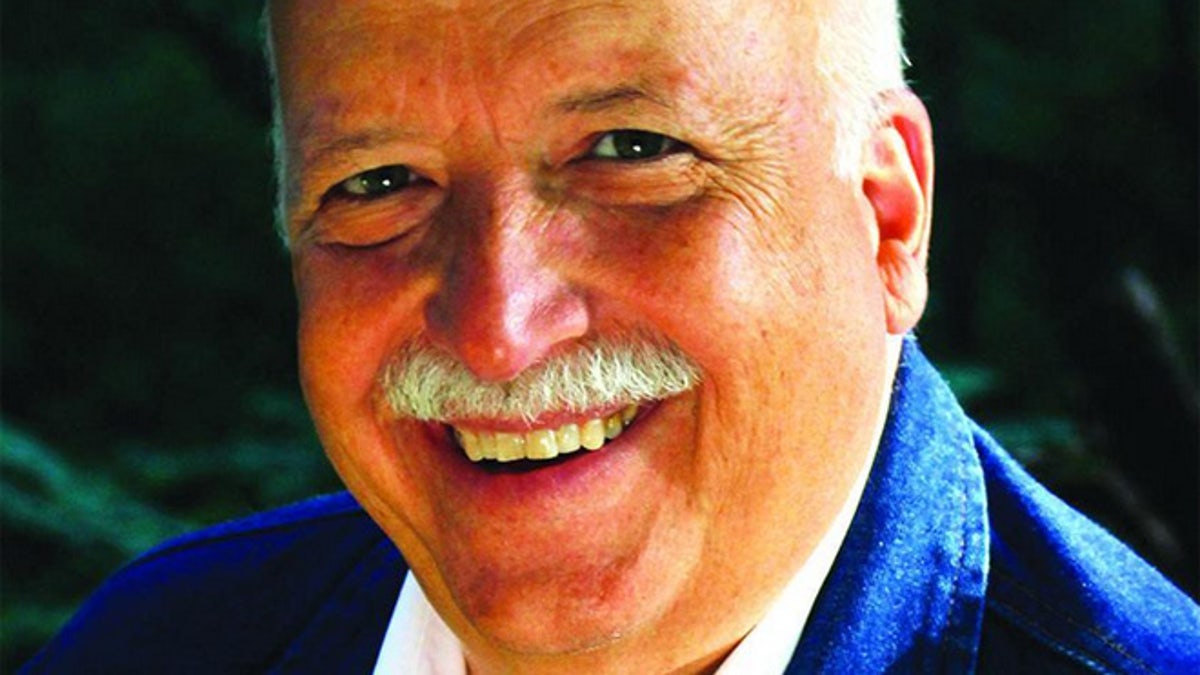

“I think the players knew the significance,” Scott Ellsworth, author of the just-released book, "The Secret Game: A Wartime Story of Courage, Change, and Basketball's Lost Triumph." “The game was covered up, but I think everyone involved knew they were part of something special.”

"They didn't want anyone to know what was going on. Who knows what would have happened if they were caught?"

The Eagles were a juggernaut that played with a pace and style few had ever seen. Where 40 or 50 points were typically enough to win games in the era of set shots and Converse Chuck Taylors, the Eagles, whose players went by flamboyant nicknames like "Boogie-Woogie" and "Big Dog"-- would routinely score 90 points with a dizzying arsenal of passing, long-range shots and smooth play under the basket. Yet the team, led by legendary coach John. B McLendon, who would go on to become the ABA's first African-American coach, could never measure itself against the great college teams in the days of segregated sports, as both the dominant National Invitational Tournament and the then-upstart NCAA tourney barred black colleges.

The Durham News & Observer identified the players for the Eagles from the left as Coach John B. McLendon, George Parks, an unidentified player, Billy Williams, James Hardy, Aubrey 'Stinkey' Stanley, Floyd Brown, Henry 'Big Dog' Thomas and manager Edward “Pee Wee” Boyd. (NCCU Archives & Records)

Word had spread around Durham about the Eagles. Pressure mounted on the Duke team to take them on, and a game was set. The Duke Medical School team was former All-Americans now in graduate school and was widely seen as the best team in the land. Dick Thistlewaite, a former star at the University of Richmond, played center. David Hubbell, an ex-forward at Duke; Homer Sieber, who had played for Roanoke College and Dick Symmonds, a onetime star at Central Methodist in Missouri were on the team. And Jack Burgess, a Montana native and former college star known for speaking out against segregation, was a leader on the team and in the locker room.

Scott Ellsworth is the author of "The Secret Game: A Wartime Tale of Courage, Change, and Basketball's Lost Triumph."

The Eagles were coming off a 26-1 season, and were led by Aubrey Stanley, Henry (Big Dog) Thomas, Floyd (Cootie) Brown and James (Boogie-Woogie) Hardy. Black players from the north were generally more comfortable with the idea with playing whites than their southern teammates, who worried about the ramifications of a hard foul or the unlikely event of a fight breaking out, Ellsworth said.

Players from Duke had concerns of their own, and used borrowed cars and circuitous routes to the Eagles' home court to assure they were not followed. Once the teams were gathered in the gym, the doors were locked.

"They didn't want anyone to know what was going on," Ellsworth said. "Who knows what would have happened if they were caught?"

The game started slow, but the Eagles soon fell into their familiar groove, Eagles' player Aubrey Stanley, who was 16, told Ellsworth in an interview.

"About midway through the first half I suddenly realized: 'Hey, we can beat these guys. They aren't supermen. They are men like us,'" Stanley said.

Outside the gym, students at the school started to notice unusual cars parked at the gym and unsuccessfully tried to gain access to the gym.

"So they climbed window ledges to look inside the gym," Ellsworth said. He pins the number of spectators outside somewhere around 50. The only reporter present, a writer from The Carolina Times, Durham's black weekly newspaper, watched the game but did not report on it.

The Eagles won, by an unofficial score of 88-44. After the game, the players decided to hang around for one more game, this time splitting into two integrated teams, Ellsworth said.

Despite its significance, the game was nearly lost to history. Decades later, Ellsworth would learn about it at a chance encounter with McLendon, fittingly at the Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Mass., gave Ellsworth, a lifelong basketball fan and avid writer, an idea for an article that would run in The New York Times in 1996. Ellsworth found himself fascinated by McLendon, a trailblazer who conditioned his players by sending them out on long country runs, years before jogging became a workout staple. McLendon, who was also one of the last students instructed by Naismith, kept a list of "Racial Firsts" that he took part in over his decades-long career.

There was one item on the list that especially piqued Ellsworth's interest.

"It said: first black and white basketball game in college, Duke medical and North Carolina College for Negroes, 1944,'" he said. "I couldn’t believe my eyes: 1944."

The game came between seminal moments in sports segregation history: Jesse Owens' landmark performance at the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games and Jackie Robinson's historic signing with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Yet it also took two decades before the wider Civil Rights movement would take hold in America. The Eagles continue to play basketball, and just missed qualifying this year for the N.C.A.A. tournament.

Ellsworth said research for the book took him to 25 states and he conducted about four-dozen interviews with players and students from the two schools. Most of those who witnessed the game have since died, but judging by the interviews Ellsworth had with the players, he believes they knew the significance of the game from the opening tip off.

Illustrating the point, Ellsworth recalled in a letter Burgess wrote to his family in Montana.

"Well, we did and we sure had fun and I especially had a good time, for most of the fellows playing with me were Southerners," Burgess wrote. "And when the evening was over, most of them had changed their views quite a lot."