Photographing Tuesday's historic Venus transit of the sun is special enough on its own, but one space photographer managed to get NASA's Hubble Space Telescope in the frame as well.

Venus crossed the sun's face from Earth's perspective on Tuesday (June 5), marking the last such Venus transit until December 2117. Astrophotographer Thierry Legault captured the rare event, and his shot shows Hubble accompanying the planet on its trek across the solar disk.

Legault traveled to Australia to observe Venus' nearly seven-hour transit. But he had to act fast to catch the Earth-orbiting Hubble Space Telescope as it zipped across the sun's face in less than a second.

"I was in northeast Australia for the full transit of Venus and a transit of Hubble in the middle," Legault told the website SpaceWeather.com. "My Nikon D4 digital camera was working at 10 fps on a Takahashi FSQ-106ED telescope to record nine images of HST during its 0.9s transit."

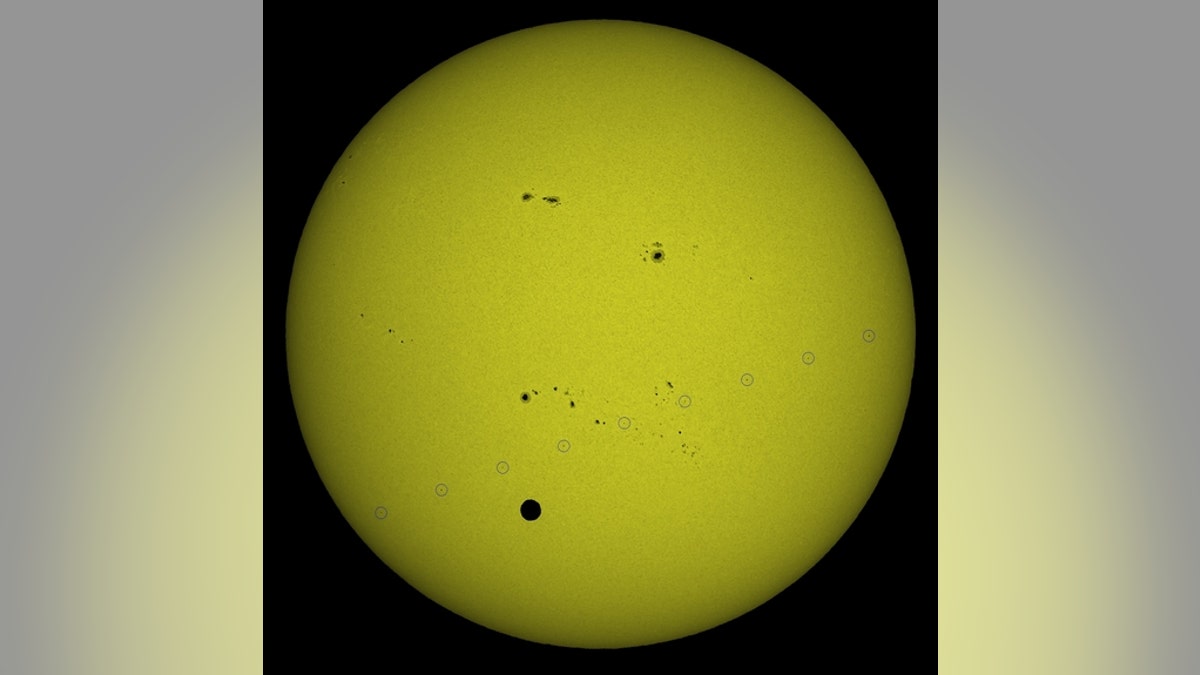

Hubble is visible in Legault's photo as a tiny black speck, while Venus appears as a much larger black disk slightly below the venerable telescope. A smattering of dark sunspots is also visible in the image. [Skywatcher Photos of the 2012 Venus Transit]

Legault explained how he photographed Venus and Hubble together in an entry on his website.

Venus transits occur in pairs eight years apart, but these dual events happen on average less than once per century. The most recent transit occurred in 2004; before that, the last ones took place in 1874 and 1882.

Researchers observed Tuesday's transit to calibrate their instruments and test out ways to study the atmospheres of alien planets. But astronomers used to await these rare events even more eagerly, as Venus transits offered a way to investigate one of science's biggest mysteries — the size of the solar system.

Back in the 18th century, scientists knew the solar system's relative scale. They were aware, for example, that Jupiter orbited the sun about five times farther out than Earth did. But they didn't know the actual distances involved.

In 1716, astronomer Edmond Halley, of comet fame, suggested a way to get the answer: Send teams to many different spots around the globe to observe a Venus transit. By noting the precise start and stop time of the transit from various locations, researchers could calculate the Earth-sun distance using the principles of parallax. With this information in hand, the rest of the solar system's distances would follow.

Huge expeditions were mounted for the transits of 1761 and 1769. Both failed to deliver the information needed to calculate the Earth-sun distance, known as an astronomical unit, with the desired precision. But scientists got the data they needed by photographing the 19th century's two Venus transits.