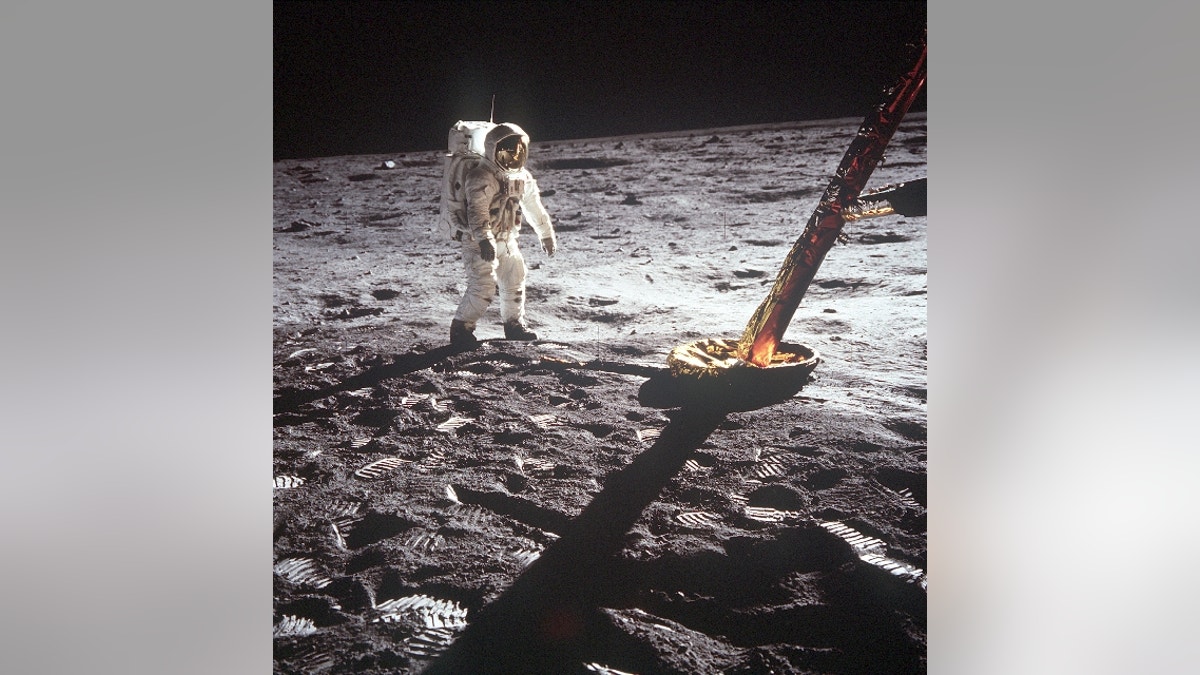

Buzz Aldrin walks on the surface of the moon near a leg of the lunar module in this photo snapped by fellow Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong.

NASA's big moon push may be coming at just the right time.

The space agency is working to land astronauts at the lunar south pole by 2024, as part of a program called Artemis that seeks to establish a long-term, sustainable human presence on and around Earth's nearest neighbor.

NASA originally targeted 2028 for this crewed lunar landing — the first since the Apollo era — but Vice President Mike Pence accelerated the timeline this past March.

Related: Can NASA Really Put Astronauts on the Moon in 2024?

On Thursday (June 13), NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine told CNN that making the 2024 landing happen will probably require an extra $20 billion to $30 billion on top of the agency's normal budget. That works out to an additional $4 billion to $6 billion per year through 2024 for NASA, which gets about $20 billion annually these days.

It's not clear at the moment if Artemis and the aggressive 2024 landing date enjoy enough support in Congress to get that much money, said space policy expert John Logsdon, a professor emeritus of political science and international affairs at George Washington University's Elliott School of International Affairs in Washington, D.C.

"The Senate has to deal with authorization and appropriations, and they've been pretty silent," Logsdon told Space.com.

(The White House is of course behind the initiative, one confusing recent tweetnotwithstanding. President Trump kicked off the crewed moon effort in December 2017 with the signing of Space Policy Directive 1.)

Gauging Artemis' funding prospects is especially complicated because there are so many variables in play, Logsdon said. For example, it's unclear if the Office of Management and Budget has signed on to the White House's plan.

Logsdon also cited the uncertainty surrounding NASA's monetary commitment to the International Space Station. The agency aims to end direct funding to the orbiting lab in the mid-2020s, but it has signaled an intent to provide money indirectly, via private companies that aim to expand the commercialization of low-Earth orbit.

And there's another variable, which could play in Artemis' favor — the fast-approaching 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing, which occurred on July 20, 1969. The wave of nostalgia that's already building in the public consciousness certainly won't hurt the new project's prospects, Logsdon said.

That's not to imply that Bridenstine's cost estimate was cagily or cynically timed.

"I think it's a coincidence of timing, and, from the advocates' point of view, probably a positive coincidence," Logsdon said.

NASA aims to achieve Artemis' ambitious goals using a giant rocket called the Space Launch System and a crew capsule called Orion, both of which are still in development. The agency also plans to build a small space station called the Gateway in lunar orbit, which will serve as a jumping-off point for sorties to the surface.

NASA doesn't view Artemis as an end in itself. The program is designed to help humanity learn how to live and work in deep space, so that NASA and its partners can get astronauts to the ultimate human-spaceflight destination: Mars.

- Apollo 11 at 50: A Complete Guide to the Historic Moon Landing Mission

- NASA's Historic Apollo 11 Moon Landing in Pictures

- In Photos: President Donald Trump and NASA

Original article on Space.com.