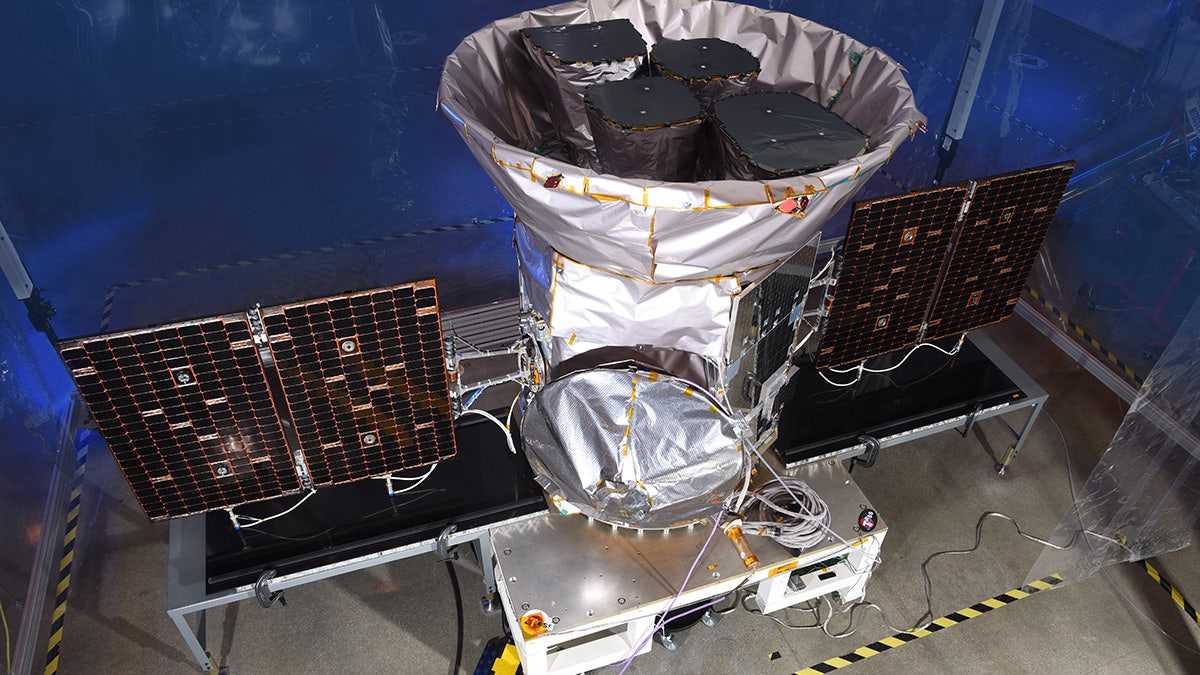

NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which launched in April 2018, is expected to discover thousands of new alien worlds. (Orbital ATK)

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. — NASA's newest planet-hunting powerhouse, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), leaped into orbit Wednesday evening (April 18) atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

TESS lifted off from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station here at 6:51 p.m. EDT (2251 GMT), then separated from its rocket ride 49 minutes later.

"When you come off the top of the rocket, all the fun for us spacecraft folks begins," Robert Lockwood, TESS spacecraft program manager for Orbital ATK, the company that built the satellite for NASA, said during a prelaunch news conference here on Sunday (April 15). [NASA's TESS Exoplanet-Hunting Mission in Pictures]

What sort of fun will Lockwood and his colleagues be having? Well, TESS' solar arrays will soon deploy, and the refrigerator-size satellite will perform a series of system checks over the next five days to ensure everything is in working order. And "first light" will come soon: TESS' science instrument, which consists of four CCD cameras, will be switched on about eight days after launch, mission team members have said.

More From Space.com

And then there's all the maneuvering. TESS is headed for an orbit around Earth that no spacecraft has ever occupied — a highly elliptical path in which the satellite will circle the planet twice for every orbit the moon completes.

This orbit is very stable, letting the spacecraft remain relatively unaffected by orbital debris and space radiation, as well as allowing for easy communications with mission team members on the ground during the close passes to Earth. Moreover, TESS shouldn't have to perform too many attitude corrections in this orbit, mission team members have said. If the spacecraft veers off course too much, the moon's gravity will pull it back in line.

However, this type of orbit presents challenges as well. For example, the timing has to be just right to sync up with the moon. If all goes according to plan, TESS will perform a beautifully choreographed orbital ballet of sorts, completing a series of maneuvers in order to fly by the moon on May 17. (TESS' cameras won't be on during this flyby, so don't expect any photos.) Approximately two months after launch, in mid-June, the spacecraft will finally reach its operating orbit.

Then, TESS' science work will begin. The satellite may be small, but it packs a major science punch. TESS is following in the footsteps of NASA's famed Kepler space telescope and is expected to surpass its predecessor in the number of exoplanets detected.

Over the course of its two-year mission, TESS will monitor the brightness of more than 200,000 stars, waiting to observe tiny dips in starlight known as transits. When a planet orbits in front of its host star, it temporarily blocks a tiny portion of starlight, and these dips will be recorded by TESS' four ultrasensitive cameras. Kepler has used this same strategy to find more than 2,600 confirmed alien worlds to date.

Some of the first images TESS' cameras collect may resemble television static rather than discernable cosmic objects, but the photos will be jam-packed with data. The mission will rely on observations by other telescopes, both on the ground and in space, to confirm which of its detected "candidates" are bona fide planets. In addition, some confirmed TESS planets should be close enough to Earth to be studied in detail by other instruments, including NASA's $8.8 billion James Webb Space Telescope, which is scheduled to launch in 2020.

TESS will observe 85 percent of the sky over its two-year prime mission and is expected to discover thousands of new worlds, as well as other astronomical objects like galaxies. We could see the first of those worlds later this year, NASA officials have said.

Originally published on Space.com.