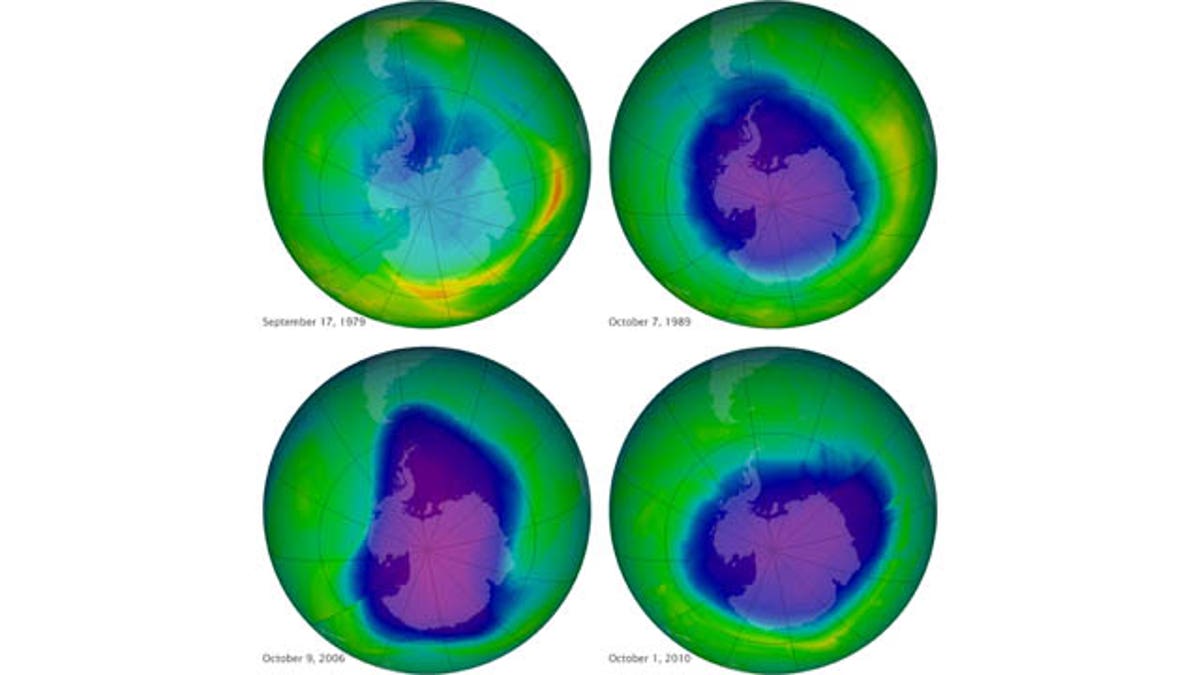

This undated image provided by NASA shows the ozone layer over the years, Sept. 17, 1979, top left, Oct. 7, 1989, top right, Oct. 9, 2006, lower left, and Oct. 1, 2010, lower right. Earth's protective, but fragile ozone layer is finally starting to rebound, says a United Nations panel of scientists. (AP Photo/NASA)

WASHINGTON – Earth's protective ozone layer is beginning to recover, largely because of the phase-out since the 1980s of certain chemicals used in refrigerants and aerosol cans, a U.N. scientific panel reported Wednesday in a rare piece of good news about the health of the planet.

Scientists said the development demonstrates that when the world comes together, it can counteract a brewing ecological crisis.

For the first time in 35 years, scientists were able to confirm a statistically significant and sustained increase in stratospheric ozone, which shields the planet from solar radiation that causes skin cancer, crop damage and other problems.

From 2000 to 2013, ozone levels climbed 4 percent in the key mid-northern latitudes at about 30 miles up, said NASA scientist Paul A. Newman. He co-chaired the every-four-years ozone assessment by 300 scientists, released at the United Nations.

"It's a victory for diplomacy and for science and for the fact that we were able to work together," said chemist Mario Molina. In 1974, Molina and F. Sherwood Rowland wrote a scientific study forecasting the ozone depletion problem. They won the 1995 Nobel Prize in chemistry for their work.

The ozone layer had been thinning since the late 1970s. Man-made chlorofluorocarbons, called CFCs, released chlorine and bromine, which destroyed ozone molecules high in the air. After scientists raised the alarm, countries around the world agreed to a treaty in 1987 that phased out CFCs. Levels of those chemicals between 30 and 50 miles up are decreasing.

The United Nations calculated in an earlier report that without the pact, by 2030 there would have been an extra 2 million skin cancer cases a year around the world.

Paradoxically, heat-trapping greenhouse gases — considered the major cause of global warming — are also helping to rebuild the ozone layer, Newman said. The report said rising levels of carbon dioxide and other gases cool the upper stratosphere, and the cooler air increases the amount of ozone.

And in another worrisome trend, the chemicals that replaced CFCs contribute to global warming and are on the rise, said MIT atmospheric scientist Susan Solomon. At the moment, they don't make much of a dent, but they are expected to increase dramatically by 2050 and make "a big contribution" to global warming.

The ozone layer is still far from healed. The long-lasting, ozone-eating chemicals still lingering in the atmosphere create a yearly fall ozone hole above the extreme Southern Hemisphere, and the hole hasn't closed up. Also, the ozone layer is still about 6 percent thinner than in 1980, by Newman's calculations.

Ozone levels are "on the upswing, but it's not there yet," he said.

Achim Steiner, executive director of the U.N. Environment Program, said there are encouraging signs that the ozone layer "is on track to recovery by the middle of this century."

Steiner called the effort to get rid of ozone-destroying substances "one of the great success stories of international collective action in addressing a global environmental change phenomenon."

"More than 98 percent of the ozone-depleting substances agreed over time have actually been phased out," he said. If not for such efforts, Steiner said, "we would be seeing a very substantial global ozone depletion today."

Paul Wapner, a professor of global environmental politics at American University, said the findings are "good news in an often dark landscape" and send a message of hope to world leaders meeting later this month in New York for a U.N. climate summit.

"The precedent is truly important because society is facing another serious global environmental problem, namely climate change," said Molina, a professor in San Diego and Mexico City. The 71-year-old scientist said he didn't think he would live to see the day that the ozone layer was rebuilding.