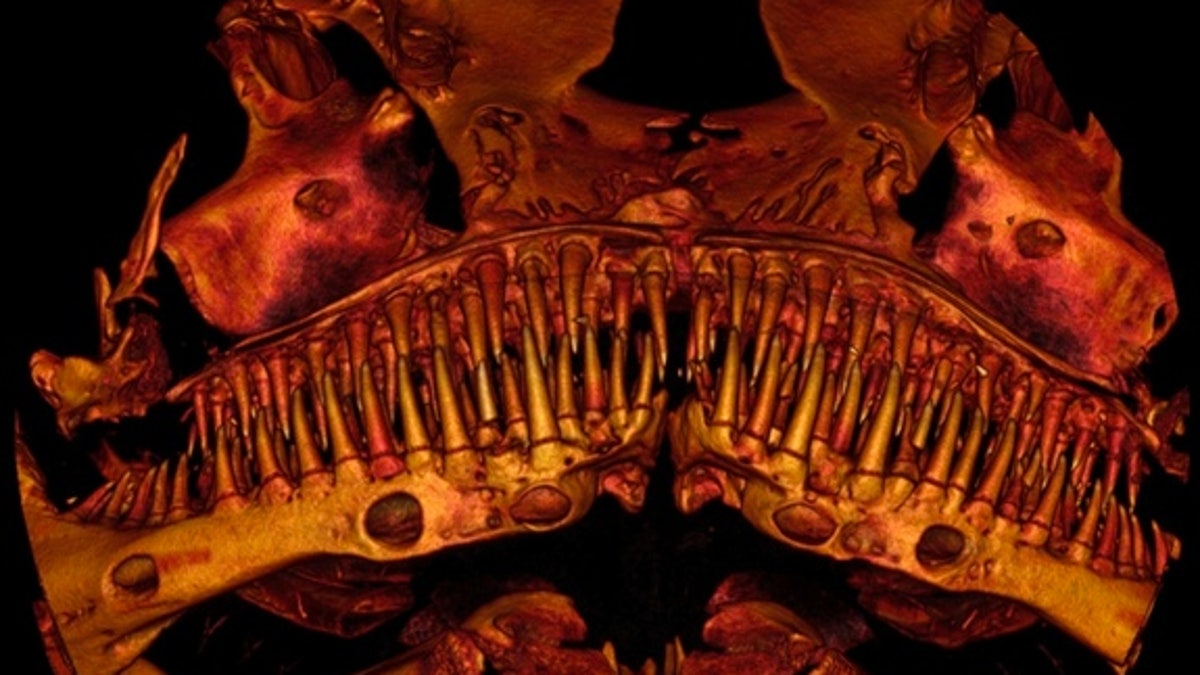

Here, a close-up scanned image of the bony structures in the toothy face of the catfish called Kryptoglanis shajii that lives in the Western Ghats mountains in India. (Mark L. Riccio, Cornell University BRC CT Imaging Facility)

A small, toothy fish, which researchers say resembles the terrifying creature from the movie "Alien," is turning out to be a big mystery for the scientists who study it.

Kryptoglanis shajii is a tiny, subterranean catfish with a number of defining skeletal features, including a bulging lower jaw similar to a bulldog's. The fish's strange, bony face has baffled researchers, who have been unable to classify the odd species.

Humans rarely catch sight of the tiny catfish, and it inhabits only one area in the world: the Western Ghats mountain range in Kerala, India. Though the fish lives underground, it has been known to emerge occasionally in the springs, wells and flooded rice paddies of the region.

[See Photos of the Weird Toothy Catfish]

The subterranean dweller is so elusive that scientists didn't categorize it as a new species until 2011. At that time, John Lundberg, emeritus curator of ichthyology at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in Philadelphia, also began taking a closer look at the new breed of fish.

"The more we looked at the skeleton, the stranger it got," Lundberg, Drexel's resident fish zoologist and a professor in the university's School of Arts and Sciences, said in a statement. "The characteristics of this animal are just so different that we have a hard time fitting it into the family tree of catfishes."

From the outside, Kryptoglanis shajii looks similar to other catfish, but a closer look inside the fish yields some surprising discoveries, Lundberg said. He and his colleagues used digital radiography and high-definition CAT scans to study Kryptoglanis' bone structure, finding that the fish is missing several bony elements.

That discovery alone was not enough to cause a stir among the experts, who explain that many subterranean fish lack some of the bones possessed by others of their species. What did surprise the researchers, however, was that the shapes of some of Kryptoglanis' bones were utterly unique among fishes of any species.

Numerous individual bones in the catfish's face are modified, giving it a compressed front end with a jutting lower jaw similar to a bulldog's snout. The tiny fish also possesses four rows of conical, sharp-tipped teeth, the researchers said.

Lundberg speculates that these multiple, unique bone structures in one part of the fish's body could mean that there is a functional purpose behind all the strangeness.

"In dogs, that was the result of selective breeding," Lundberg said. "In Kryptoglanis, we don't know yet what in their natural evolution would have led to this modified shape."

The researchers seem to have ruled out the possibility that the catfish's unusual mug resulted from a highly specialized diet. That's because, based on the fish's teeth and subterranean habitat, it most likely eats a relatively typical diet of small invertebrates and insect larvae, Lundberg said. Video footage of live specimens at feeding time also suggests that this tiny fish at 4 inches, it's smaller than the average adult's pinky finger is perfectly capable of eating such food.

The mystery of Kryptoglanis has received attention from other researchers, as well. Ralf Britz, a fish researcher at the Natural History Museum of London, led a separate study of the species' unique bone structure. The research was published in the March 2014 issue of the journal of Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters.

Unlike Lundberg's study, which used high-resolution X-ray computed tomography to create three-dimensional CAT scan images of the fish's skeleton, Britz and his team utilized a technique known as clearing and staining. This method of visualizing a skeleton uses chemicals to render the fish's soft tissues in clear glass and its bones and cartilage in contrasting, colored glass.

Yet, much about the catfish remains mysterious. For instance, neither study was able to definitively conclude why Kryptoglanis is so unique among fishes, or what species it counts as its closest relatives.

The new study, led by Lundberg, is published in the 2014 issue of the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.