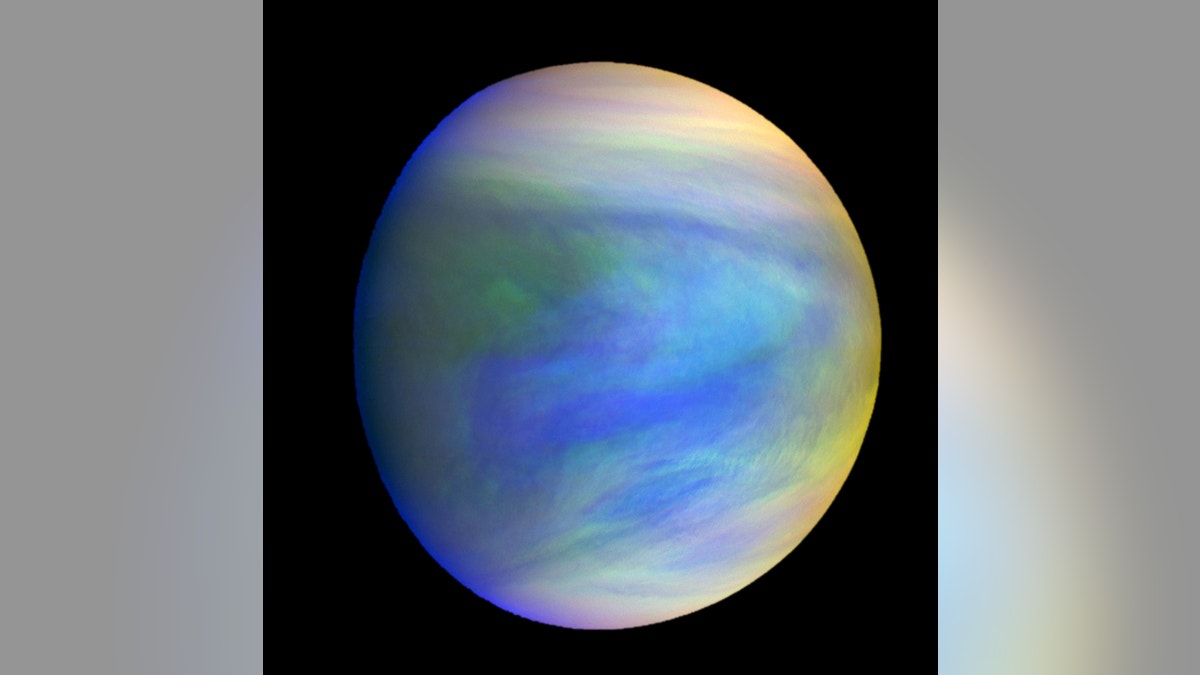

A composite image of Venus as seen by Japan's Akatsuki spacecraft. Venus' spin varies because of atmospheric waves over the planet's mountains, according to a new study. (JAXA)

Venus is an extraordinarily beautiful hellscape: its clouds are made of sulfuric acid, its surface is so hot it would melt even lead, and its winds constantly hit hurricane-force speeds.

That's why very few robots have made their mark on the Venusian surface, and why none have lasted more than 2 hours. But scientists are desperate for a better understanding of what's happening on the planet's surface — and that's why they're talking through the science a long-lived lander, dubbed Venera-D, could do on Venus.

"Nothing's being built right now, we're not at that nuts-and-bolts stage," Tracy Gregg, a planetary geologist at the University at Buffalo and U.S. co-chair of the binational science definition committee for Venera-D, told Space.com. [Photos of Venus, the Mysterious Planet Next Door]

More From Space.com

The committee Gregg co-chairs is a joint endeavor between NASA and the Russian space agency, Roscosmos. Although NASA has historically struggled with Venus missions and focused on exploring Mars instead, Roscosmos has faced the reverse situation, having "really succeeded in smacking the surface of Venus with a bunch of landers," Gregg said.

Now, the two agencies are partnering to bring together scientists to discuss a new type of Venus mission: a lander that could survive the planet's deadly surface for not just days, but months, sending back crucial scientific knowledge about the hellish world.

That process focuses on drawing up a list of various scientific priorities and the instruments that would be necessary to address them. "What does the team want? We want everything, but that's not very helpful," Gregg said. [The Weirdest Facts About Venus]

So instead, they're talking about specific mission goals — like landing during the Venusian day and remaining at work through sunset. "Being able to observe that change from day to night would be amazing," Gregg said, since the planet rotates backward and a day lasts longer than a year.

Another key question a long-lived lander could tackle deals with Venusian volcanic activity, and particularly what that lava is made of. Scientists have seen plenty of evidence of that volcanic activity, like a 5,550-mile-long (7,700 kilometers) channel — longer than the Nile here on Earth. "That channel on Venus could not have been carved by water, it had to have been made by lava," Gregg said. Some terrestrial lava can eat into the ground like that, but it's rare. "Even if you don't know anything about geology, your response is…'Wow that's weird.'"

So there are plenty of scientific mysteries for a long-lived lander to try to tackle. "Venus just is weird; it's got stuff going on that nobody has been able to explain," Gregg said. "I was just going into this last night at the dinner table with my family."

And the good news is that despite NASA's tendency to head for Mars rather than Venus, it's much easier to get to Venus — that's why it's a favorite pit stop for missions looking for a gravity-assist maneuver to send them to their final destination. (In fact, a NASA spacecraft is making just such a flyby this week, as the Parker Solar Probe makes its way to the sun). [Japan at Venus: Photos from the Akatsuki Spacecraft's Mission]

But there are still plenty of questions left for the committee members to address as they work on preparing a report due at the end of January summarizing what they continue to learn about the feasibility of a long-lived lander on Venus.

"I am continually surprised by the necessary level of detail required to help make some of these decisions," Gregg said, adding that the team has discussed questions like when a parachute would need to deploy or how often during that descent samples should be taken. "We're really kind of micromanaging it down to the second in terms of timing and that really surprised me, I didn't think it happened at this stage."

But Gregg said that during her first science-definition process, it's really heartening to see that kind of detailed approach, because it underscores her faith in NASA's mission investment process.

"My tax dollars are not being wasted; they're not putting money on anything they don't know is going to work and give excellent science returns," Gregg said. "There aren't going to be any bad decisions made, whatever the outcome."

Original article on Space.com.