Never corner an electric eel– it might just leap out of the water and shock you. In the 19th century, German naturalist and archaeologist Alexander von Humboldt saw this firsthand in South America when he witnessed electric eels jumping out of a marsh to attack horses. Upon being electrocuted, the horses then slumped into the water and drowned.

When Vanderbilt University biologist Dr. Kenneth Catania first read von Humboldt’s account over a hundred years later, he thought it seemed a little far–fetched.

“I was very skeptical,” he told FoxNews.com. “It didn’t make sense to me that eels would attack horses.”

Related: UK faces potential moth infestation of 'biblical' proportions

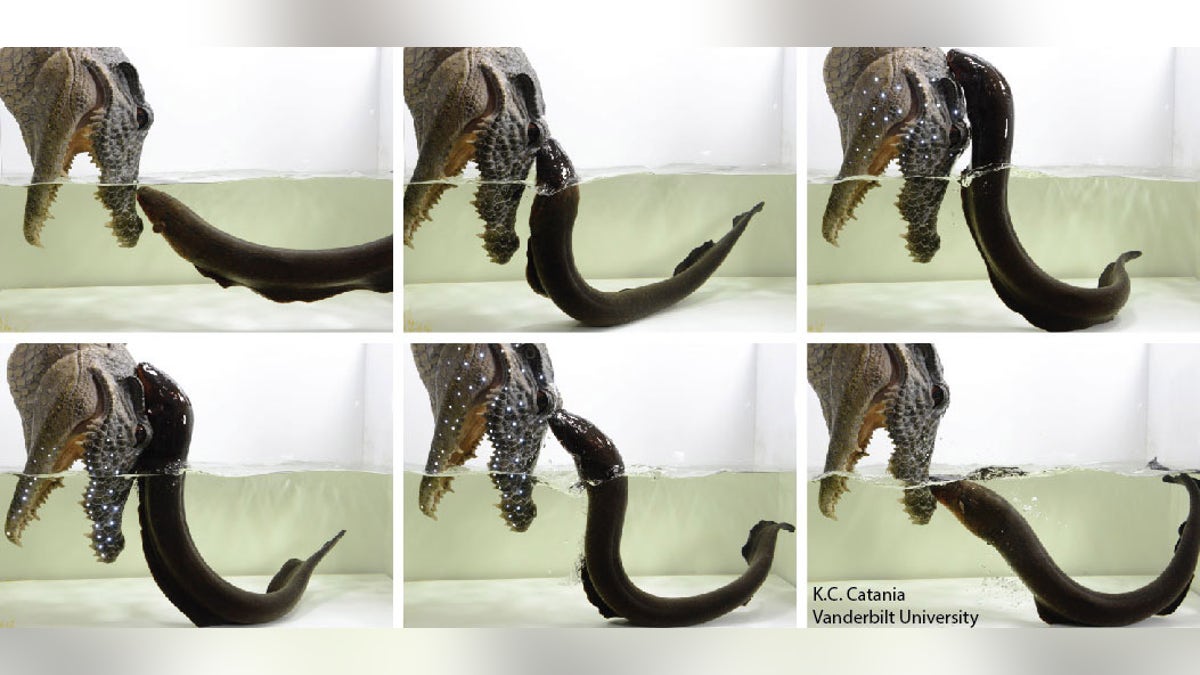

But last year Catania made an accidental discovery that lent the story some credence. While using a metal–rimmed net to scoop a large electric eel out of its tank, the eel attacked the net by pressing its chin against the handle and jumping out of the water, discharging high–voltage shocks. Luckily, Catania was wearing rubber gloves at the time.

Catania, who is the Stevenson Professor of Biological Sciences at Vanderbilt, soon found that this was an occasional defensive strategy when electric eels are cornered or threatened by partially submerged objects, behavior he detailed in his study “Leaping eels electrify threats supporting von Humboldt’s account of battle with horses.” The study can be found in the Proceedings of the National Academy online.

He says that a number of things came together that suggested Humboldt’s story was likely true.

Related: South Africa's national parks consider banning wildlife sighting apps

“Part [of it] was realizing the seasonal variations in water levels may trap electric eels in small areas, making them vulnerable to predation,” he explained. “Going back to Humboldt’s story - it was in fact the dry season, and the fishermen went to a pool where the eels were apparently trapped. These things suggested the eels would have no way to retreat, and would view the horses as threats. But of course the most obvious reason to reconsider Humboldt’s story [is that I experienced] the eel’s defensive behavior ‘first hand,’ almost literally as the eels attacked my metal net.”

To conduct his experiment, Catania hooked a voltmeter and an ammeter to an aluminum plate. With these, he measured the nature and strength of the electric shocks discharged by the eel as it jumped onto the conductor. The higher the eel leapt onto its target, the more the voltage and amperage produced by the eel increased.

The power of an eel’s electrical pulses is distributed throughout the water while it swims along fully submerged. However, when it lifts out of the water, this electrical current travels from its chin to its target. The current then courses through the prey before exiting back into the water and returning to the eel’s tail. This process allows the eel to deliver maximum power shocks to partially submerged targets.

Related: Flash mob! Glowing in fishes more widespread than thought

To visually illustrate his experiment, Catania rigged a plastic human arm and alligator head with LEDs, which lit up when the eel attacked.

“The electrical potential I measured would be the electrical potential you would experience if the eel came up your arm,” Catania said.

According to Catania, electric eel shocks are similar to that of a TASER or electric fence, and are used mostly as a deterrent or to cause temporary paralysis. His previous research showed that when an eel attacks a fish, it gives it a high frequency volley of millisecond pulses that stimulates the nerves controlling the fish’s muscles, causing them to contract and freezing the fish up.

Electric eels (which are actually knifefish) can leap up to half of their body length, sometimes more. Seeing as how adults typically measure over six feet long, that’s a pretty good distance, so you probably wouldn’t want one jumping out at you from murky water anytime soon.

“I don’t know of any case of a human being killed, but [I] can’t say I have read every account from the past 200 years,” Catania said. “Humans do get shocked when [entering] the water near an electric eel that may [feel] threatened.”