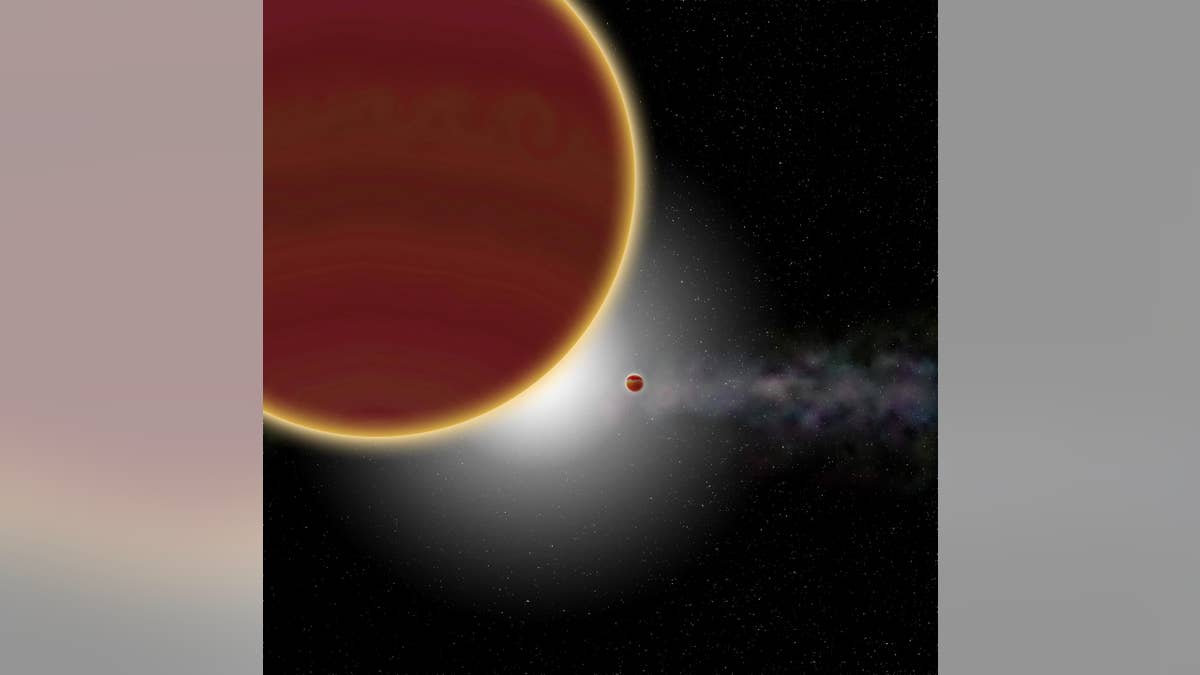

An artist's depiction of the newly discovered planet Beta Pictoris c, top left, as seen with its solar system neighbor Beta Pictoris b and backlit by the star itself. (Image: © P Rubini/AM Lagrange)

The solar system around a star called Beta Pictoris was already a pretty interesting place, with a large planet scientists have actually seen and a huge amount of rubble flying around. But it just got even more intriguing.

That's because astronomers now think they've picked up on a second planet orbiting the nearby star. The discovery is based on more than 10 years of data about minuscule changes in the star's orbit caused by the gravitational tug between the star and what scientists now believe to be a planet.

The Beta Pictoris solar system is a special one for scientists because it is fairly close to Earth, at just 63.4 light-years away, and relatively young, at about 23 million years old. That means scientists can study it to better understand the tumultuous adolescence of developing solar systems.

Related: The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)

From what scientists knew before the new research, Beta Pictoris' adolescence already looked awfully messy.

A disk of planetary rubble clutters the outer reaches of this solar system; astronomers think hunks of rock called planetesimals ricocheting into each other continues to create that debris. Those planetesimals fill the solar system from 50 astronomical units (or AU, the average distance from Earth to our sun) away from Beta Pictoris out to 100 AU. One AU is about 93 million miles, or 150 million kilometers.

About a decade ago, astronomers identified a large planet, nine to 13 times more massive than Jupiter and dubbed Beta Pictoris b, orbiting about 9 AU from the star. Unusual for exoplanets, this one has been imaged; typically, worlds are identified as shadows passing over a star's disk or as tiny wobbles in the star's location. And scientists have even spotted exocomets darting across the Beta Pictoris system, slowly losing steam as they go.

But astronomers combing through 10 years of data gathered by the European Southern Observatory's High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) program realized that what they knew about the Beta Pictoris solar system still didn't quite add up.

HARPS measures tiny changes in a star's light caused by slight movements of the star as its gravity interacts with that of a planet. For a star like Beta Pictoris, which regularly grows and shrinks, those tiny changes are very difficult to parse out from these pulses, but that is precisely what the team behind the new research did.

The astronomers were left with signals that they believe can be explained only by a second planet, one that is about nine times the mass of Jupiter and orbits its star once every 1,200 or so days. The planet is about 2.7 AU away from its star, equivalent to the distance from our sun to the asteroid belt.

The researchers said they hope that other techniques will be able to spot the planet, dubbed Beta Pictoris c, as well. This planet may pass directly between its star and Earth, which means scientists could study the world's atmosphere and any rings or moons that orbit it. If astronomers can directly image Beta Pictoris c, as they have its neighbor, they may also be able to answer questions about how these planets formed.

The research is described in a paper published Monday (Aug. 19) in the journal Nature.

- Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets

- The Most Fascinating Exoplanets of 2018

- 7 Ways to Discover Alien Planets

Original article on Space.com.