Saturn's turbulent jet streams are powered by the huge planet's internal heat rather than by energy from the sun, a new study suggests.

Heat from deep within Saturn causes water to condense, which in turn creates temperature differences in the atmosphere, researchers said. These temperature differences generate disturbances that accelerate the planet's jet streams — regions where winds blow much faster than in other parts of the atmosphere.

"We know the atmospheres of planets such as Saturn and Jupiter can get their energy from only two places: the sun or the internal heating," study lead author Tony Del Genio, of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York, said in a statement. "The challenge has been coming up with ways to use the data so that we can tell the difference."

Del Genio is on the imaging team for NASA's Cassini spacecraft, which made the observations the team analyzed in the new study.

Studying Saturn's winds

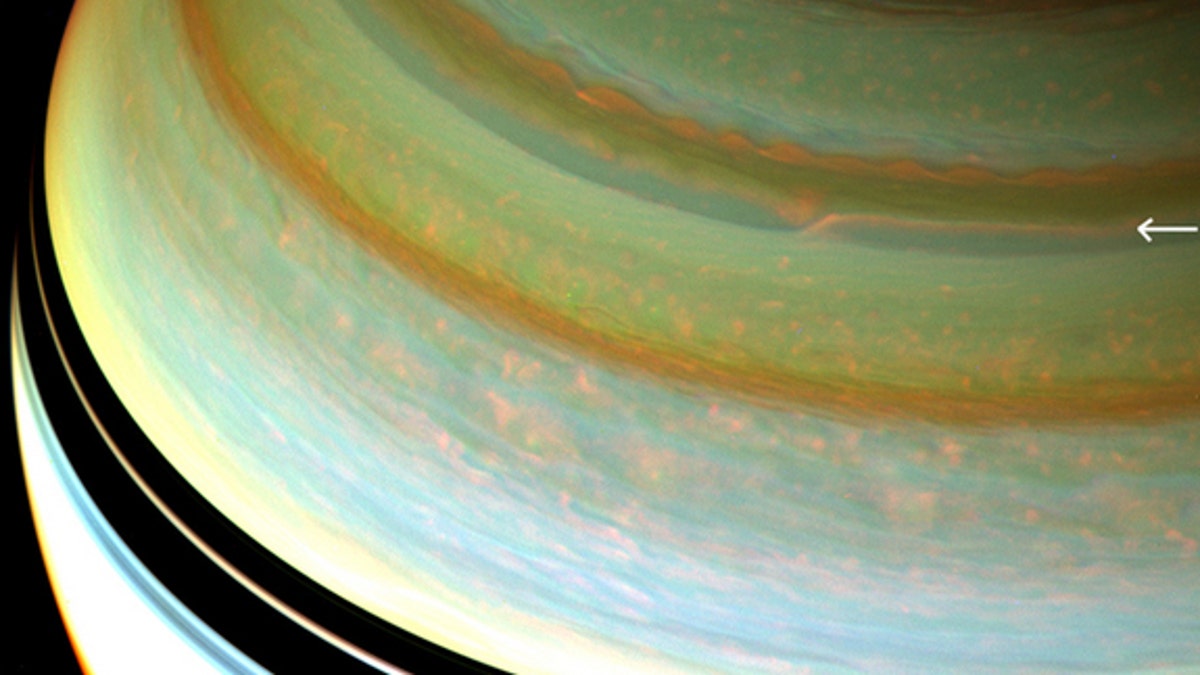

Many different jet streams whip through Saturn's thick atmosphere, some of them high enough up to be spotted by the optical and near-infrared filters of Cassini's cameras, researchers said. Most of the gas giant's jet streams blow eastward, but some blow to the west instead. [Photos: The Rings and Moons of Saturn]

To better understand the behavior and origin of these jet streams, Del Genio and his colleagues used automated software to analyze the movements and speeds of clouds captured in hundreds of Cassini images from 2005 through 2012.

"With our improved tracking algorithm, we've been able to extract nearly 120,000 wind vectors from 560 images, giving us an unprecedented picture of Saturn's wind flow at two independent altitudes on a global scale," said co-author John Barbara, also at the Goddard Institute for Space Studies.

One of those altitudes is the upper troposphere, a relatively high layer where heating by the sun is strong. The other layer is much deeper down, at the tops of ammonia ice clouds where solar heating is weak, researchers said.

The atmospheric disturbances that give rise to Saturn's jet stream are weak in the upper layer but much stronger deeper down, the team found. So it appears that solar heating is not driving the jet streams.

Rather, the scientists think that internal heat from Saturn is stirring up water vapor from the planet's interior. This water vapor condenses in places as air rises, releasing heat as clouds and rain are produced. It is this heat that ultimately drives the jet streams. Such condensation heating is also the chief driver of storms on Saturn, researchers said.

The scientists published their results in the June issue of the journal Icarus.

Different than Earth

If the researchers are correct, then Saturn's jet streams are fundamentally different than the ones we observe here on Earth, which are powered by heat from the sun.

"Understanding what drives the meteorology on Saturn, and in general on gaseous planets, has been one of our cardinal goals since the inception of the Cassini mission," said Cassini imaging team lead Carolyn Porco, of the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo. "It is very gratifying to see that we're finally coming to understand those atmospheric processes that make Earth similar to, and also different from, other planets."

Cassini launched in 1997 and arrived at Saturn in 2004. It has been studying the ringed planet and its many moons ever since, and will continue to do so for at least another half-decade. Two years ago, NASA extended the probe's mission to at least 2017.