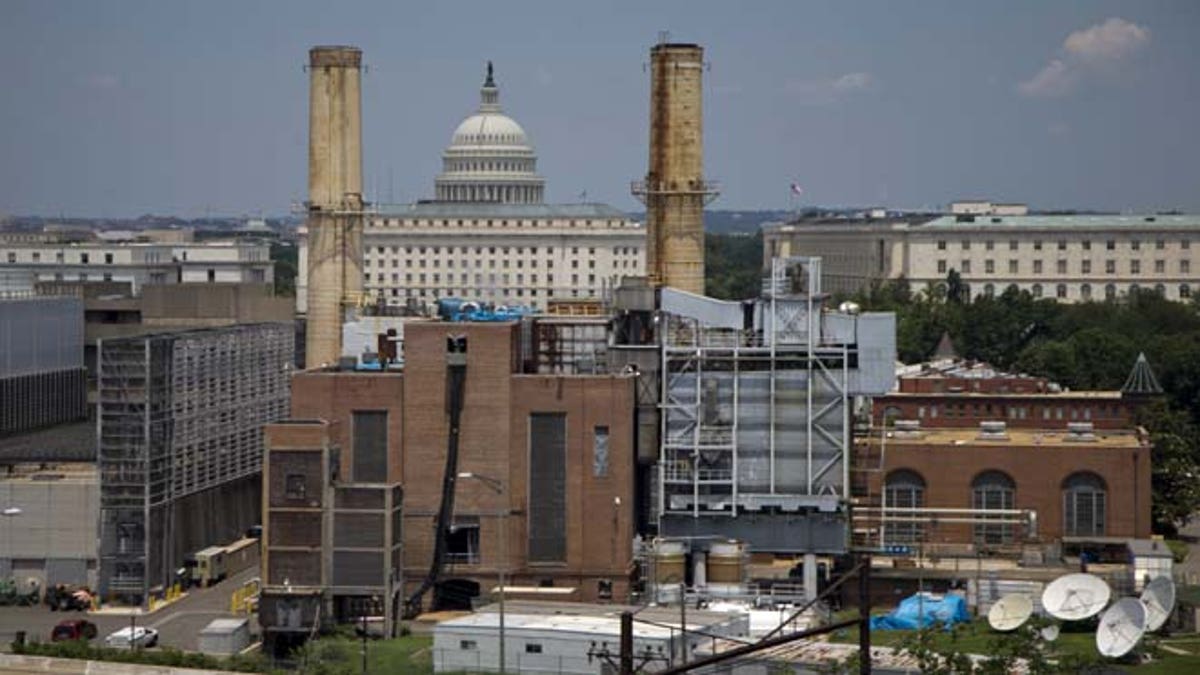

The Capitol Dome is seen behind the Capitol Power Plant in Washington, Monday, June 24, 2013. The plant provides power to buildings in the Capitol Complex. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

President Obama will announce Tuesday he is planning to sidestep Congress to implement a national plan to combat climate change that will include the first-ever federal regulations on carbon dioxide emitted by existing power plants, despite adamant opposition from Republicans and some energy producers.

In a speech at Georgetown University Tuesday, Obama will announce he's issuing a presidential memorandum to implement the regulations, meaning none of the steps involved in the plan will require congressional approval.

In addition, Obama will say he is directing his administration to allow enough renewables on public lands to power 6 million homes by 2020, effectively doubling the capacity from solar, wind and geothermal projects on federal property.

Obama also was to announce $8 billion in federal loan guarantees to spur investment in technologies that can keep carbon dioxide produced by power plants from being released into the atmosphere.

In taking action on his own, Obama is also signaling he will no longer wait for lawmakers to act on climate change, and instead will seek ways to work around them.

The linchpin of Obama's plan, and the step activists say will have the most dramatic impact, involves limits on carbon emissions for new and existing power plants. The Obama administration has already proposed controls on new plants, but those controls have been delayed and not yet finalized.

Tuesday's announcement will be the first public confirmation that Obama plans to extend carbon controls to coal-fired power plants that are currently pumping heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere.

"This is the holy grail," said Melinda Pierce of Sierra Club, an environmental advocacy group. "That is the single biggest step he can take to help tackle carbon pollution."

However, critics say that Obama's changes will create more problems for America's coal industry.

"This proposal will buttress an EPA proposed rule issued last year for new power plants that will essentially ban coal’s use in the future," Tom Borelli, a senior fellow at FreedomWorks, told FoxNews.com.

Forty percent of U.S. carbon dioxide emissions, and one-third of greenhouse gases overall, come from electric power plants, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the Energy Department's statistical agency.

Obama is expected to lay out a broad vision Tuesday, without detailed emission targets or specifics about how they will be put in place. Instead, the president will launch a process in which the Environmental Protection Agency will work with states to develop specific plans to rein in carbon emissions, with flexibility for each state's circumstances.

Under one scenario envisioned by the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental group, states could draw on measures such as clean energy sources, carbon-trapping technology and energy efficiency to reduce the total emissions released into the air.

Heather Zichal, Obama's senior energy and climate adviser, told environmental groups Monday that Obama is working with Housing and Urban Development Secretary Shaun Donovan on a target for renewable energy to be produced at federally assisted housing projects.

She framed the Obama's efforts in the U.S. as part of a broader, global movement to combat climate change, trumpeting the role the U.S. can play in leading other nations to stem the warming of the planet.

Paul Bledsoe, who worked on climate issues in the Clinton White House, said Zichal renewed a pledge Obama made in in his first year in office, during global climate talks in Copenhagen, to cut U.S. carbon emissions by about 17 percent by 2020, compared to 2005 levels.

"This is a policy fulfillment of what the president has been talking about and trying to accomplish for five years or more," said Bledsoe, now a senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

One key issue Obama is not expected to address Tuesday is Keystone XL, a pipeline that would carry oil extracted from tar sands in western Canada to refineries along the Texas Gulf Coast. A concerted campaign by environmental activists to persuade Obama to nix the pipeline as a "carbon bomb" appears to have gained little traction. The oil industry has been urging the president to approve the pipeline, citing jobs and economic benefits.

Obama raised climate change as a key second-term issue in his inaugural address in January, but has offered few details since. In his February State of the Union, he issued an ultimatum to lawmakers: "If Congress won't act soon to protect future generations, I will."

The poor prospects for getting any major climate legislation through a Republican-controlled House were on display last week when Speaker John Boehner responded to the prospect that Obama would put forth controls on existing power plants by deeming the idea "absolutely crazy."

"Why would you want to increase the cost of energy and kill more American jobs?" said Boehner, R-Ohio, echoing the warnings of some industry groups.

Sidestepping Congress by using executive action doesn't guarantee Obama smooth sailing. Lawmakers could introduce legislation to thwart Obama's efforts. And the rules for existing power plants will almost certainly face legal challenges in court. The Supreme Court has upheld the EPA's authority to regulate greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act, but how the EPA goes about that effort remains largely uncharted waters.

Even if legal and political obstacles are overcome, it will take years for the new measures to be put in place, likely running up against the end of Obama's presidency or even beyond it. White House aides say that's one reason Obama is ensuring the process starts now, while there are still more than three years left in his final term.

Under the process outlined in the Clean Air Act, the EPA cannot act unilaterally, but must work with states to develop the standards, said Jonas Monast, an attorney who directs the climate and energy program at Duke University. An initial proposal will be followed by a months-long public comment period before the EPA can issue final guidance to states. Then the states must create actual plans for plants within their borders, a process likely to take the better part of a year.

Then the EPA has another four months to decide whether to approve each state's plan before the implementation period can start.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.