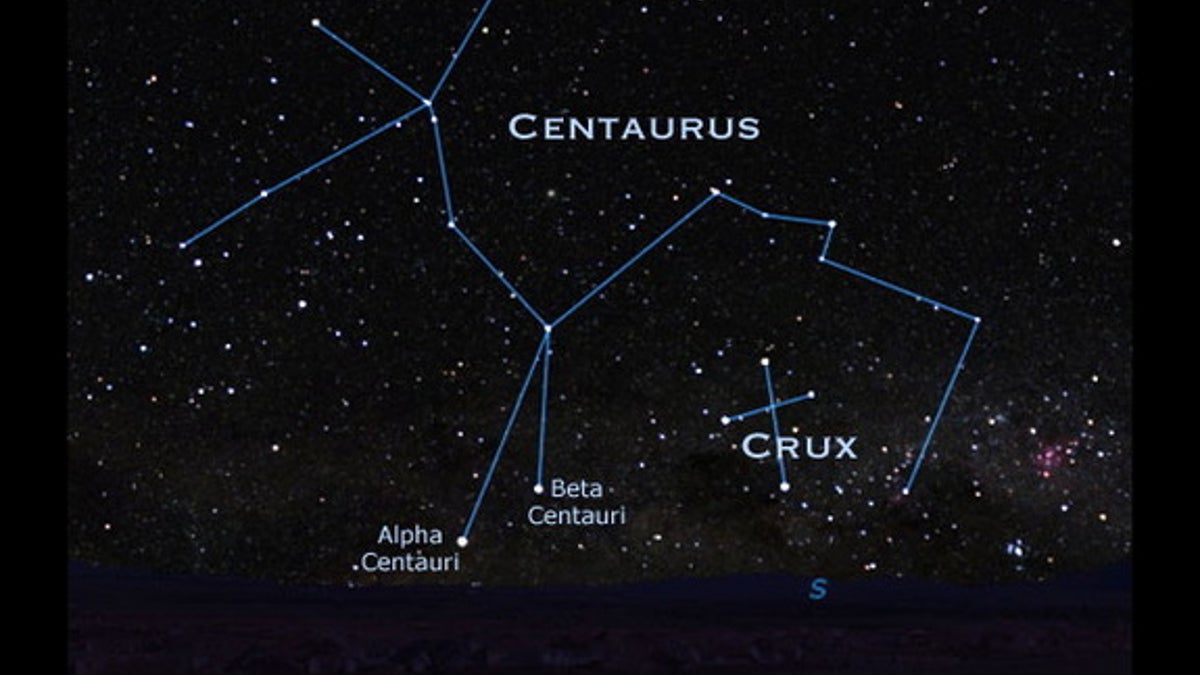

Centaurus constellation includes Alpha Centauri and Beta Centauri. (Starry Night Education)

One of the most interesting of the constellations is now dominating the low southern sky at around 9:30 p.m. local daylight time — the mythical half-horse, half-man creature known as the Centaur.

Actually, this particular star pattern, known as Centaurus, is one of two centaurs in our night sky. The other is Sagittarius, the Archer, who traditionally has been depicted as a centaur about to shoot an arrow in the direction of Scorpius, the Scorpion.

Centaurus can be seen completely from the Florida Keys, southernmost Texas and the Hawaiian Islands. Yet in the high latitudes of southern England, an assiduous stargazer must carefully watch the southern horizon for a short look at the 2nd-magnitude star Menkent (about as bright as Polaris, the North Star). In the northern United States, we can use Menkent (also known as Theta Centauri), to guide us to other stars in the constellation such as Iota Centauri and Eta Centauri. [Best Stargazing Events for June (Sky Maps)]

Omega: A great ball of stars

Centaurus is also home to Omega Centauri. This is not a single star but a great swarm of them — indeed, the brightest and most splendid globular cluster in the entire sky.

Shining at a moderately dim magnitude +4, it is easy to glimpse under good sky conditions with the naked eye. Omega Centauri has, in fact, been known since ancient times (albeit as a star). It appeared in the star catalogue of Ptolemy over 18 centuries ago and received the Greek letter designation of Omega from Johannes Bayer.

Edmond Halley (of comet fame) called Omega a nebula in 1677. It was not until 1835 that its true glory as a cluster was revealed by the 18.75-inch telescope that Sir John Herschel took to South Africa to survey the southern skies.

Of Omega, Herschel wrote: "It is beyond all comparison the richest and largest object of its kind in the heavens." Omega Centauri is about 17,000 light-years away and probably contains more than one million stars.

In 1986, I led a tour to Easter Island and the Chilean Andes to view Halley’s Comet and had an opportunity to view the southern skies firsthand. My view of Omega Centauri through a 3.1-inch refracting telescopewas nothing short of amazing — a great ball of stars so closely packed in the center that it appeared as a blur of light.

Theoretically, Omega Centauri can be seen from places as far north as New York or Philadelphia. But I can offer no encouragement to residents of the Big Apple or the City of Brotherly Love, because even if all of their streetlights were somehow extinguished and a fresh, clean Canadian air mass positioned itself directly over the northeastern U.S., the thick haze that is perpetually evident along and near the horizon almost always hides Omega.

And even if one were to somehow get it in view through a telescope, the cluster would be robbed of its full glory. To see Omega Centauri adequately, one should be no farther north than about latitude 35 degrees.

Our nearest stellar neighbors

Of course, Centaurus' greatest claim to fame is that it contains the nearest star in the sky, Rigil Kentaurus. That isn't how this particular star is best known; more often than not, it is referred to by the designation Alpha Centauri.

This is the third-brightest star in the sky and is also a beautiful double star, composed of two yellow stars somewhat like the sun. Alpha Centauri is a mere 4.3 light-years from us and has a faint 11th-magnitude companion about 2 degrees away known as Proxima Centauri. Proxima’s position relative to the main pair actually places it a trifle closer to us at the present time. [Alpha Centauri Stars & Planet Explained (Infographic)]

To the upper right of Alpha is the first-magnitude Beta Centauri, which has the name Hadar and seems to be a neighbor. But in reality, Hadar — a blue star about 10,000 times brighter than the sun — lies about 500 light-years away.

And then there’s the Wolf

Just to the east of Centaurus is Lupus, the Wolf. Allegorical star pictures often show Lupus impaled on a sword triumphantly held by the Centaur; perhaps he killed the Wolf while hunting and offered it to the gods as a sacrifice. But in his classic star guide, "The Stars: A New Way to See Them," H.A. Rey depicts Lupus as "trotting beneath one arm of the Centaur, who seems about to seize him." No matter. Lupus' stars seem to be entangled with those of Centaurus, so it is perhaps best to study the two constellations together.

Although none of them are very bright, the dozen or so stars of Lupus make for a sparkling display between Centaurus immediately to the west and the stars of Scorpius to the east.

In their way, the ancients had imaginations as facile and fanciful as ours. While some of us would people the universe with little green men, they placed in the sky a number of exotic beasts of which Centaurus is just one. In the sky itself, we are hard put to imagine the mythological character in the confusing jumble of stars that form Centaurus. This star pattern is often associated with the mythological centaur, Chiron, who was highly skilled in medicine.

This leaves me ending this column with a question. If a centaur fell ill, who would he consult: a physician or a veterinarian?