Fox News Flash top headlines for April 29

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

No stranger to shooting lasers at the moon, NASA will once again send a laser to Earth's celestial satellite to look for water on the surface that may be hidden.

The government space agency said it is working on developing a small satellite (CubeSat) known as a Lunar Flashlight to look for surface ice that may be at the bottom of craters on the moon that never see sunlight.

"Although we have a pretty good idea there's ice inside the coldest and darkest craters on the Moon, previous measurements have been a little bit ambiguous," said Barbara Cohen, principal investigator of the mission at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, in a statement. "Scientifically, that's fine, but if we're planning on sending astronauts there to dig up the ice and drink it, we have to be sure it exists."

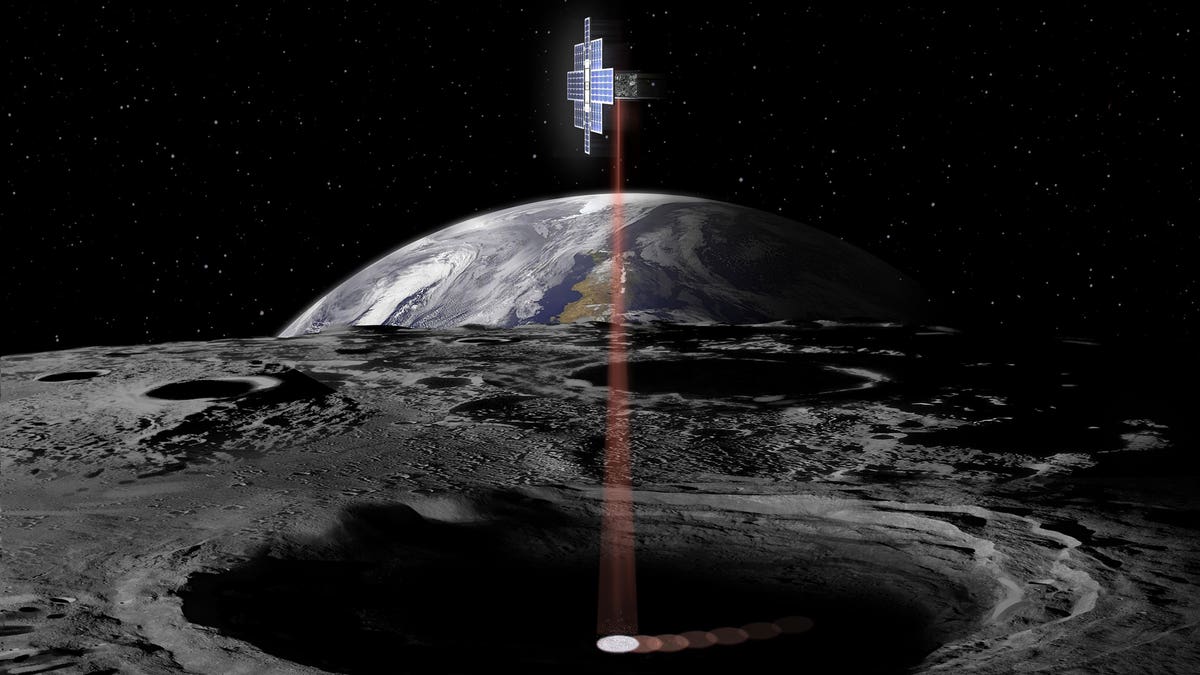

This artist's concept shows the Lunar Flashlight spacecraft, a six-unit CubeSat designed to search for ice on the moon's surface using special lasers. The spacecraft will use its near-infrared lasers to shine light into shaded polar regions on the moon, while an onboard reflectometer will measure surface reflection and composition. Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

WATER MAY BE ALL OVER THE MOON, GIVING NEW HOPE FOR SUSTAINED LIFE

The Flashlight, which is being managed by NASA JPL, will look to become not only the first mission to look for water using lasers, but also use a new "green" fuel, one that is safer to transport and store.

"A technology demonstration mission like Lunar Flashlight, which is lower cost and fills a specific gap in our knowledge, can help us better prepare for an extended NASA presence on the Moon as well as test key technologies that may be used in future missions," John Baker, Lunar Flashlight project manager at JPL, added.

Researchers have known for some time about the existence of that water on the moon, having first discovered water vapor as early as 1971. In 2009, the first evidence of frozen water on the surface was discovered.

In recent years, experts have learned more about water ice on the moon, including details about its age, discovery at the polar regions, as well as the fact it may exist all over.

The mission, proposed in a research paper, will last two months and see the satellite hover over the South Pole of the moon to look for surface ice in the craters that are largely hidden from view.

"We will also be able to compare the Lunar Flashlight data with the great data that we already have from other Moon-orbiting missions to see if there are correlations in signatures of water ice, thereby giving us a global view of surface ice distribution," Cohen explained.

"The Sun moves around the crater horizon but never actually shines into the crater," Cohen said. "Because these craters are so cold, these molecules never receive enough energy to escape, so they become trapped and accumulate over billions of years."

The proposed mission comes in advance of NASA's Artemis program, which is intended to land American astronauts on the moon by 2024, as well as establish a sustainable human presence on Earth’s natural satellite.

The successor to the Apollo program, the timing of Artemis could be delayed due to the worldwide coronavirus pandemic.

Fox News' James Rogers contributed to this story.