Fox News Flash top headlines for August 28

Fox News Flash top headlines for August 28 are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com

A new study has revealed a surprising secret about exoplanets known as "hot Jupiters" — the dark sides of those planets have "surprisingly uniform" temperatures, suggesting the clouds could be made of minerals and rocks.

The research looked at 12 exoplanets and found that the temperatures on the nightsides of these planets were all around 800 degrees Celsius, suggesting there's some kind of natural energy transfer going on.

"Atmospheric circulation models predicted that nightside temperatures should vary much more than they do," said the study's lead author, Dylan Keating, in a statement. "This is really surprising because the planets we studied all receive different amounts of irradiation from their host stars and the dayside temperatures among them varies by almost 1700°C [3092 F]."

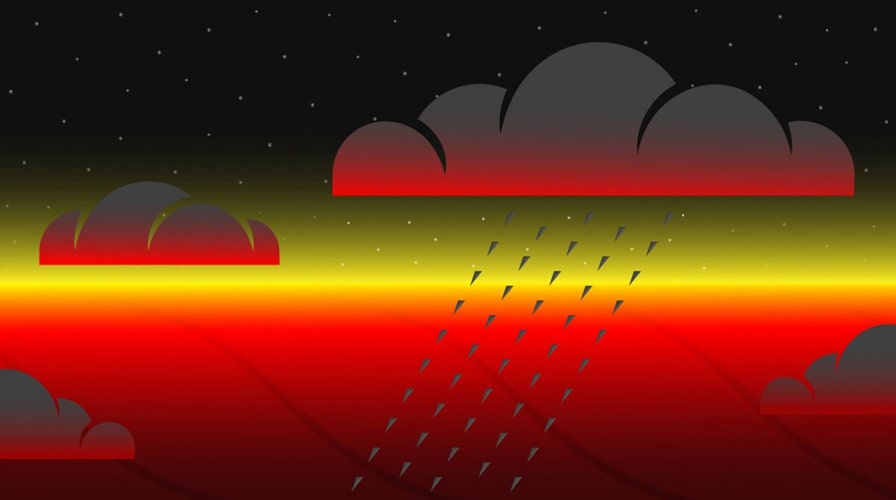

Schematic of clouds on the night side of a hot Jupiter exoplanet. The underlying atmosphere is over 800 C, hot enough to vaporize rocks. Atmospheric motion from the deep atmosphere or from the hotter dayside bring the rock vapour to cooler regions, where it condenses into clouds, and possibly rains down into the atmosphere below. These clouds of condensed rock block outgoing thermal radiation, making the planet's nightside appear relatively cool from space. Credit: McGill University

ANCIENT MARS WAS WARM AND RAINY ENOUGH TO SUPPORT LIFE, STUDY SAYS

These exoplanets are known as "hot Jupiters" because they are gas giants just as Jupiter is, but are significantly warmer. Because of its distance from the Sun, Jupiter's temperature measurements vary more on height. In the clouds, temperatures average approximately minus 234 degrees Fahrenheit, whereas near the center of the planet, the temperature is a toasty 43,000 degrees Fahrenheit, NASA notes.

Keating and the other researchers used data from NASA's Spitzer telescope and the Hubble Space Telescope.

The researchers believe that it's possible that "nightside clouds" are the reason behind the similar temps.

"This result can be explained if most hot Jupiters have nightside clouds that are optically thick to outgoing longwave radiation and hence radiate at the cloud-top temperature, and progressively disperse for planets receiving greater incident flux," the study's abstract states. "Phase-curve observations at a greater range of wavelengths are crucial to determining the extent of cloud coverage, as well as the cloud composition on hot Jupiter nightsides."

According to NASA, more than 4,000 exoplanets have been discovered so far and there are another 3,000 "candidates" that require further observation to determine if they are real.

The study has been published in the scientific journal Nature Astronomy.