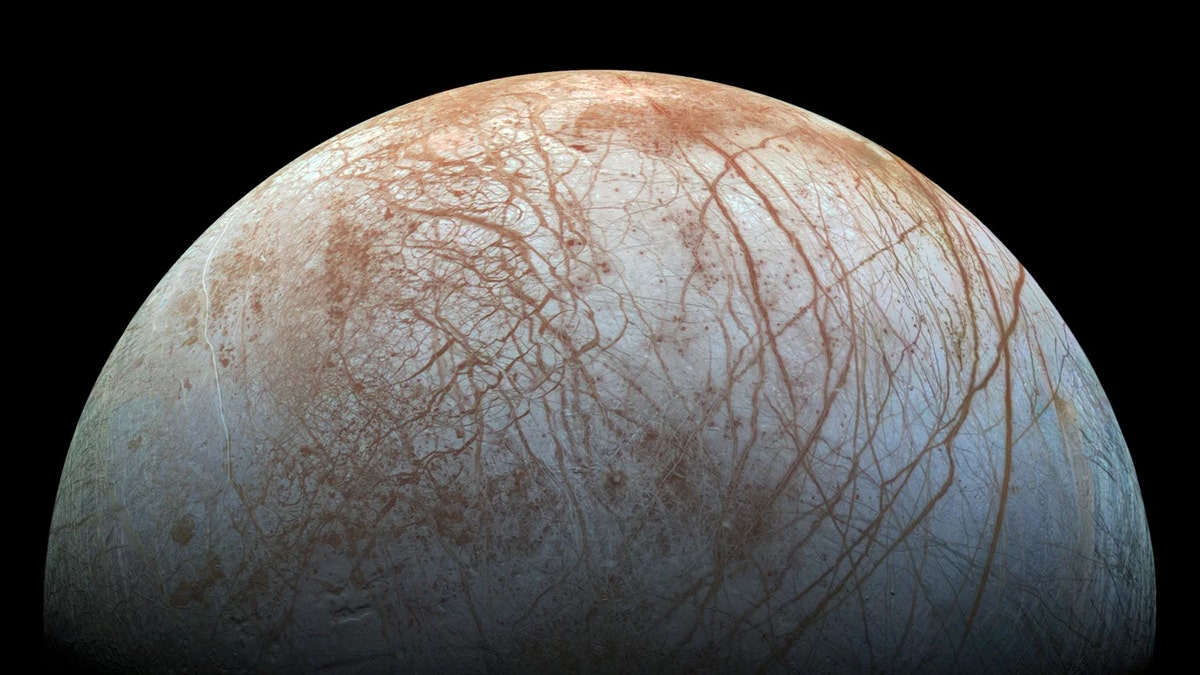

Jupiter's moon Europa, as photographed by NASA's Galileo spacecraft. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SETI Institute

Europa may be the most likely place to host alien life. Beneath its surface is a salty ocean, warmed by the play of gravity on the moon’s metal core. But how do you peer through sheet ice?

You melt your way down, with a nuclear-powered robot.

At least that’s the proposal put to the American Geophysical Union meeting in Washington DC this week.

NASA’s Glenn Research center’s multidisciplinary COMPASS team was established to develop technology to overcome the challenges of space exploration.

Europa poses a big one.

The ice that covers this moon of Jupiter could be anywhere between 2 and 30km thick.

But, beneath, could be life.

And finding it will throw open our understanding of how common life is in our universe, how resilient it is — and how it arises.

NUCLEAR TUNNELBOT

Planetary scientists aren’t even certain Europa has an ocean. But all the signs indicate it has. The most enticing of these are the plumes of liquid-water which periodically erupt from its surface.

The COMPASS team has completed a concept study on the technologies capable of piercing the ice with a suite of sensors and sending the data it collects back to Earth.

The best option, they argue, is a nuclear-powered ‘tunnelbot’.

Nuclear power packs the most energy into a small space.

And it doesn’t even need to be built into a nuclear reactor — though that was one of the concept designs. In its simplest form, radioactive ‘bricks’ would simply radiate a heat source in front of a tube-shaped probe which then gradually sinks as the ice beneath turns to slush.

The power of such nuclear fuel cells have been amply demonstrated by the likes of Voyager 1 and 2, still sending back signals as they cross into interstellar space some 40 years after they were launched.

ICE PIERCER

The nuclear ‘tunnelbot’ would deploy from a lander with a fiber-optic string of data ‘repeaters’ unfurling as it sinks.

Any such a Europa ‘tunnelbot’ would be relatively large. And risky to launch.

“We didn’t worry about how our tunnelbot would make it to Europa or get deployed into the ice,” says University of Illinois at Chicago associate professor Andrew Dombard. “We just assumed it could get there and we focused on how it would work during descent to the ocean.”

Which is the purpose of their mission. Whether or not such a nuclear-powered ‘tunnelbot’ is built and deployed is the next step. But the decision will be based upon an informed study of what it would take to take a peek under Europa’s ice.

Sending a probe to Europa is one of NASA’s major ambitions for the coming decades. But getting the mission past an increasingly skeptical US Congress may not be easy.

ON THIN ICE

The project’s chief advocate was Texas Republican John Culberson, who chaired the subcommittee that funds NASA. The NASA study which produced the nuclear-powered ‘tunnelbot’ is a result of his efforts.

But he lost his seat at the recent midterm elections.

And President Donald Trump’s most recent budget states he has no intention of funding an Europa lander.

Some experts express the fear such an attempt would be a ‘bridge too far’: we simply don’t know enough about the icy moon, yet.

“It’s a mission that came out of Congress as opposed to a mission that came out of the science,” says The Planetary Society’s Emily Lakdawalla.

Others argue the long lead-up time for such ambitious missions means now is the time to start working towards the project.

And we’re set to learn more about the mysterious moon anyway.

The Europa Clipper mission — a space probe designed to orbit the moon — has received initial funding. Its goal is to circle as low as 25km for up to three years, mapping Europa’s icy surface and gleaning what it can about chemicals being spewed out in its plumes.

It’s hoped the Clipper will be ready for launch in 2022. It will take six years for the probe to reach Jupiter and establish itself in orbit around Europa.

This story originally appeared in news.com.au.