Fox News Flash top headlines for Nov. 1

Fox News Flash top headlines for Nov. 1 are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com

For a celestial object that may or may not be a planet, Pluto sure is getting a lot of attention these days.

Just days after NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said that Pluto should be given back its planet status, the U.S. space agency announced that it has funded a study to see if another orbiter mission to the dwarf planet is feasible.

NASA has provided funding to the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) to investigate the costs of the project, its feasibility, as well as "develop the spacecraft and payload design requirements and make preliminary cost and risk assessments for new technologies," according to a statement.

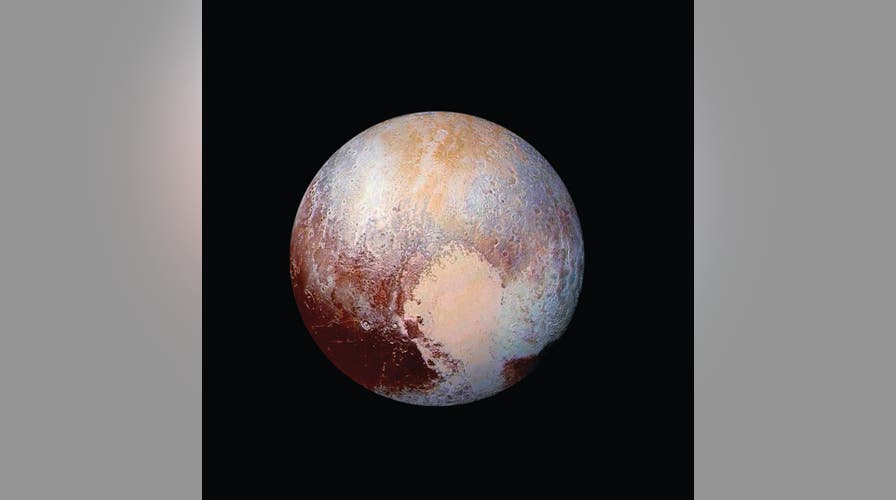

FILE - This image made available by NASA in March 2017 shows Pluto illuminated from behind by the sun as the New Horizons spacecraft travels away from it at a distance of about 120,000 miles (200,000 kilometers). (NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute via AP)

PLUTO SHOULD BE A PLANET AGAIN, RESEARCHERS ARGUE

“We’re excited to have this opportunity to inform the decadal survey deliberations with this study,” said SwRI’s Carly Howett, who is leading the project, in a statement. “Our mission concept is to send a single spacecraft to orbit Pluto for two Earth years before breaking away to visit at least one KBO [Kuiper Belt Object] and one other KBO dwarf planet.”

NASA first flew past Pluto in July 2015 with its New Horizons mission, which is managed by SwRI. Throughout that year, the space agency released a series of images of Pluto, including the first close-up image of an area near the dwarf planet's equator, which contains a range of mountains rising as high as 11,000 feet above Pluto's icy surface.

An image of the Tenzing Montes peaks on Pluto created with New Horizons data and released on July 10, 2018. The mountains range from about 1.8 miles to 3.7 miles (3 to 6 kilometers) above the dwarf planet's surface. (Paul Schenk/Lunar and Planetary Institute)

In January 2019, New Horizons, which was launched in January 2006, flew past fellow Kuiper Belt object, Ultima Thule. In May, NASA revealed a startling discovery that there are both water and "organic molecules" on its surface.

Alan Stern, SwRI's principal investigator, revealed the organization has been working on its concept for some time.

"In an SwRI-funded study that preceded this new NASA-funded study, we developed a Pluto system orbital tour, showing the mission was possible with planned-capability launch vehicles and existing electric propulsion systems," Stern added in the statement.

To follow up on NASA’s New Horizons mission that revealed Pluto’s “heart,” SwRI is studying a new Pluto orbiter mission for NASA. SwRI has shown it is possible to orbit Pluto and then escape orbit to tour additional dwarf planets and Kuiper Belt Objects. (Credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI)

“We also showed it is possible to use gravity assists from Pluto’s largest moon, Charon, to escape Pluto orbit and to go back into the Kuiper Belt for the exploration of more KBOs like MU69 and at least once more dwarf planet for comparison to Pluto.”

Pluto lost its planet status in 2006 when it was controversially demoted to “dwarf planet” by the International Astronomical Union.

Last month, Bridenstine, during a wide-ranging speech at the International Astronautical Congress, said: “I am here to tell you, as the NASA Administrator, I believe Pluto should be a planet.”

Bridenstine later responded to a question on his Pluto stance by citing its buried ocean, its five moons and its multilayered atmosphere. “I like there being nine planets, how about that?” he added.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Fox News' James Rogers contributed to this report.