Mysterious blue pigment in medieval woman's teeth gives scientists 'bombshell' clue

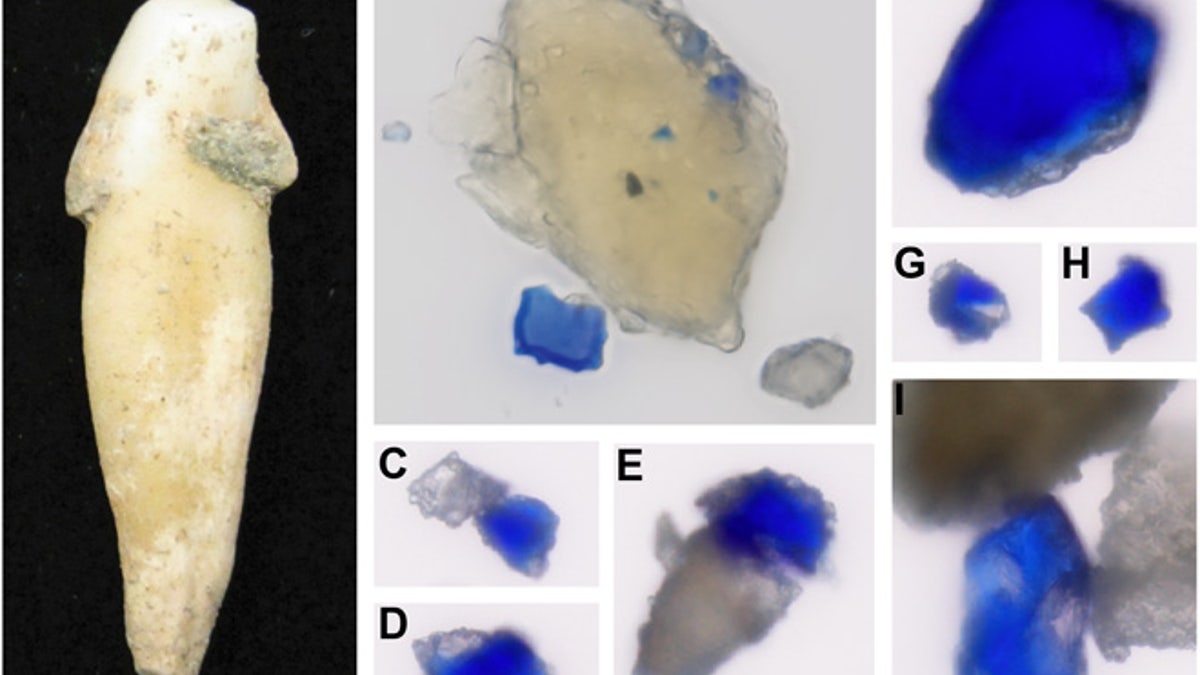

A huge discovery for scientists, who found blue flecks in the bones from a medieval woman's jaw. They were able to identify the blue particles as lapis lazuli — a deep blue, semi-precious rock that was highly prized at the time for its symbolization of royalty and godliness.

Vivid flecks of blue discovered in the teeth of a 1,000-year-old skeleton from the medieval era have given scientists a rare glimpse into an ancient woman's past.

The discovery is huge for scientists, who were able to identify the blue particles as lapis lazuli — a deep blue, semi-precious rock that was highly prized at the time for its symbolization of royalty and godliness. It's possible the stone was even once placed "in the original breastplate of the High Priest," according to Crystal Vaults. The particles were occasionally ground up and used as a pigment.

In 11th- and early 12th century Europe, lapis lazuli was traded as a luxury good and used in pricey artwork or literary works.

After carefully studying the dug-up woman's dental remains, scientists from the Department of Archaeology at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and the Laboratory of Microarchaeology at the University of York were able to conclude the woman was likely a medieval nun from Germany, according to a study published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances.

MYSTERY OF 3,000-YEAR-OLD EGYPTIAN MUMMY WITH 'MAGICAL' TATTOOS SOLVED

A thousand years ago, women weren't known for writing or painting with the coveted stone, though a lack of signatures on these pieces of art made it difficult to prove that was the case. Nonetheless, monks were known as "primary producers" of books throughout the Middle Ages, authors of the recent study point out. But evidence of a woman with lapis lazuli challenges past conceptions.

"The early use of this pigment by a religious woman challenges widespread assumptions about its limited availability in medieval Europe and the gendered production of illuminated texts," the study states.

"It's kind of a bombshell for my field — it's so rare to find material evidence of women's artistic and literary work in the Middle Ages."

This evidence shows that women at that time, particularly nuns, were "not only literate but also prolific producers and consumers of books."

Though her name remains unknown, the woman who was buried in a German churchyard was probably a highly skilled artist and scribe.

"It's kind of a bombshell for my field — it's so rare to find material evidence of women's artistic and literary work in the Middle Ages," Alison Beach, a professor of medieval history at Ohio State University and co-author of the study, said to The Associated Press. "Because things are much better documented for men, it's encouraged people to imagine a male world. This helps us correct that bias. This tooth opens a window on what activities women also were engaged in."

At that time, the precious stone was only mined in Afghanistan. So, when it was delivered to spots in Europe such as Germany and Austria, it was probably met with a big price tag. Because of the cost of carrying it to Europe, ultramarine was reserved for the most important and well-funded artistic projects.

OLDEST WEAPONS EVER DISCOVERED IN NORTH AMERICA UNCOVERED IN TEXAS

"If she was using lapis lazuli, she was probably very, very good," Beach added. "She must have been artistically skilled and experienced."

It's not entirely clear how the mystery woman ended up with specks of lapis lazuli in her teeth — but scientists do have a guess.

Lapis lazuli is a deep blue, semi-precious rock that was highly prized during the Middle Ages. (C. Warinner, M. Tromp, A. Radini/Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History)

"It is plausible to assume that artists would have occasionally licked their brushes to make a fine point, a practice that later artist manuals refer to explicitly. In doing so, pigments, such as lapis lazuli, may have been introduced into the oral cavity, where they could have become entrapped within dental calculus," the study's authors pointed out.

However, they also added that it was possible the blue pigment could have been introduced through pigment production.

Scientists hope this information gives ancient female scribes the recognition they deserve.

"If you picture someone in the Middle Ages making a fine illuminated manuscript, you probably picture a monk — a man," Beach said, noting that this find may help researchers uncover more information regarding females vital roles and contributions to society in the olden days.

The scientists arrived at the latest discovery by accident. A building renovation in 1989 uncovered the woman's tomb, along with those of other women who were apparently part of a female religious community attached to the church. Radiocarbon dating of the skeleton revealed the 45- to 60-year-old woman died between 997 and 1162.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.