Fox News Flash top headlines for April 14

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

Get all the latest news on coronavirus and more delivered daily to your inbox. Sign up here.

Scientists have developed an experimental vaccine for COVID-19 that, when delivered to mice using microneedles, caused antibody production against the disease within two weeks.

Researchers had been working to develop vaccines for other coronaviruses, including the one that causes Middle East Respiratory System (MERS). They were able to adapt the system they'd been working on produce a candidate MERS vaccine to rapidly produce an experimental vaccine using the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, according to the NIH Research Matters blog.

The team, which includes scientists from the University of Pittsburgh, developed a method for delivering their MERS vaccine into mice using a microneedle patch.

These patches look like a very small piece of velcro, but they contain hundreds of microneedles composed of sugar. The needles would prick the skin and dissolve, releasing the vaccine.

ANTIBODY POINTS TO POTENTIAL WEAK SPOT ON NOVEL CORONAVIRUS

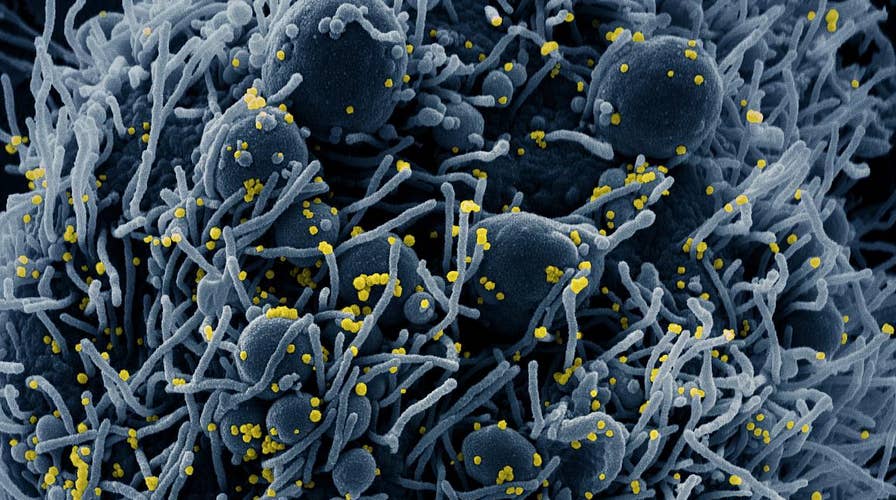

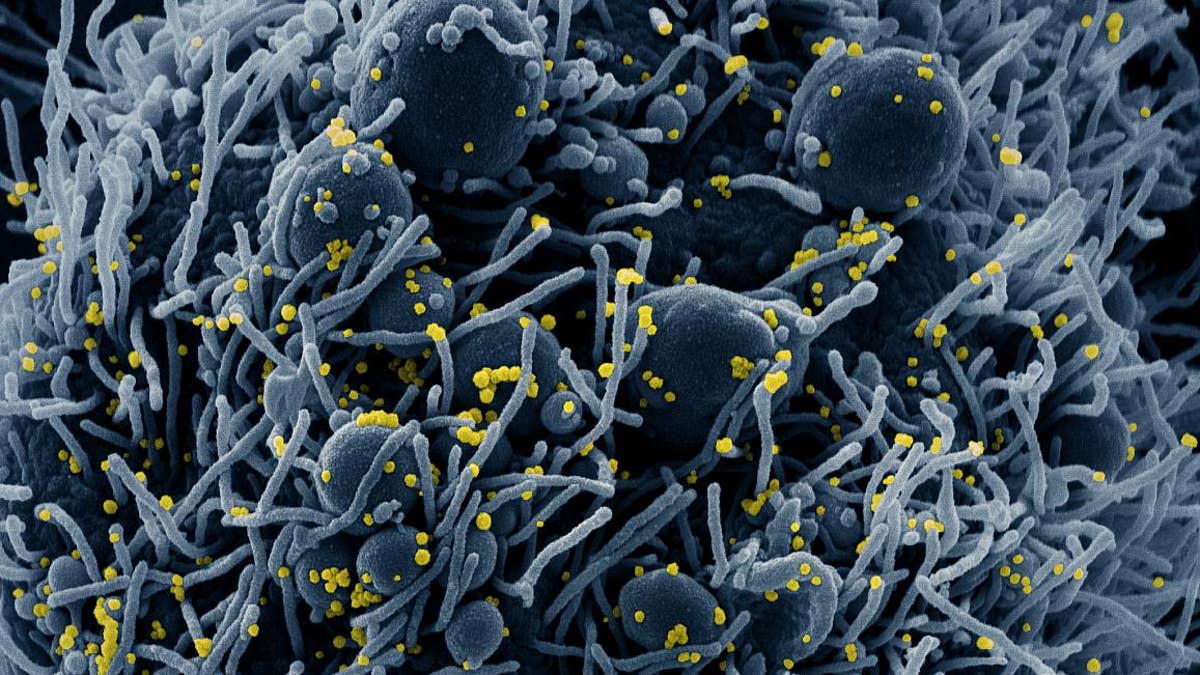

Colorized scanning electron micrograph of an apoptotic cell (blue) infected with SARS-COV-2 virus particles (yellow), isolated from a patient sample. Image captured at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. NIAID

The NIH notes that the immune system is highly active in the skin, so delivering vaccines this way could produce a more rapid and robust immune response than standard injections under the skin.

When delivered by microneedle patch to mice, three different experimental MERS vaccines induced the production of antibodies against the virus. Antibody levels continued to increase over time in mice vaccinated by microneedle patch — up to 55 weeks, when the experiments ended.

Using knowledge gained from development of the MERS vaccine, the team made a similar microneedle vaccine targeting the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. The vaccine prompted robust antibody production in the mice within two weeks.

The study, which was funded by the National Institute of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), and National Cancer Institute (NCI), appeared online on April 1, 2020, in EBioMedicine, a Lancet journal.

However, researchers cautioned that the vaccinated animals have not been tracked for long enough to determine if the long-term immune response is equivalent to what was observed with the MERS vaccine. Nor have the mice been challenged with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

FOXCONN WORKERS IN CHINA FACE DAILY TEMPERATURE CHECKS, THERMAL SCREENINGS

The components of the experimental vaccine could be made quickly and at large scale, according to the researchers, and the final product doesn’t require refrigeration -- so it could be produced and put in storage until needed.

The team now wants to obtain approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to launch a phase 1 trial within the next several months.

Still, much work needs to be done by scientists to explore the safety and efficacy of this candidate vaccine. “Testing in patients would typically require at least a year and probably longer,” said Dr. Louis Falo Jr. of the University of Pittsburgh in a statement to the NIH blog. “This particular situation is different from anything we’ve ever seen, so we don’t know how long the clinical development process will take.”

Scientists -- including NIH Director Dr. Anthony Fauci -- have said that developing an effective vaccine for COVID-19 would take about 12 to 18 months.