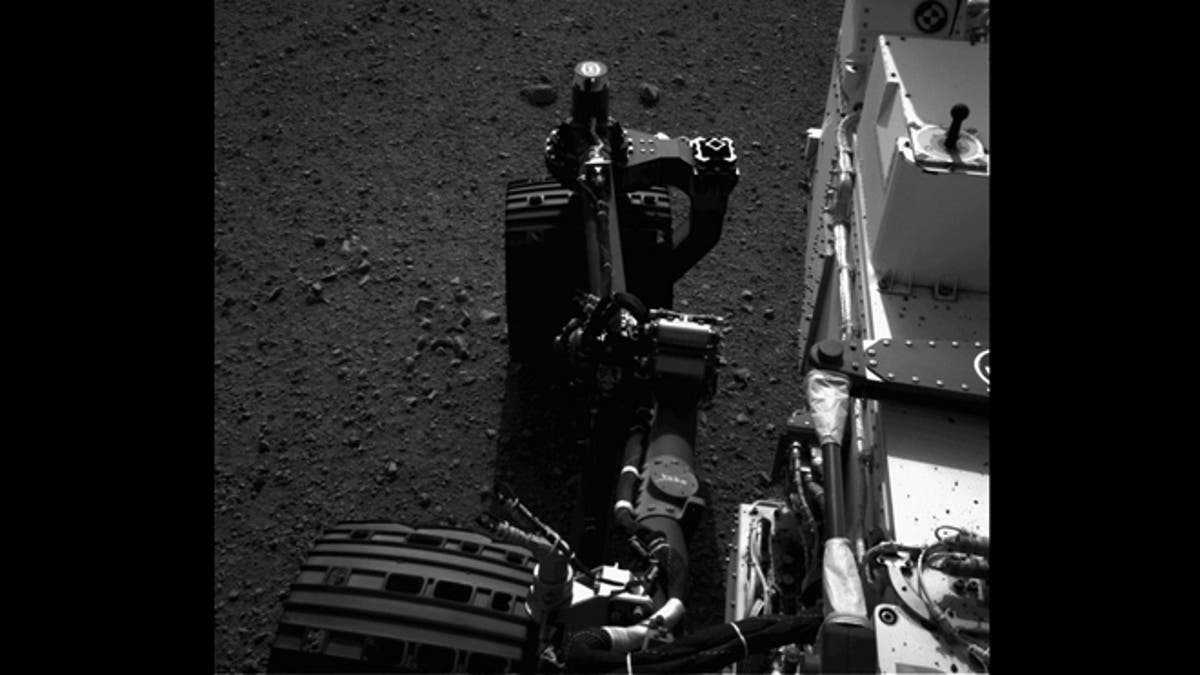

This still from a set of images shows the movement of the front left wheel of NASA's Curiosity as rover drivers turned the wheels in place at the landing site on Mars. Engineers wiggled the wheels as a test of the rover's steering and anticipate embarking on Curiosity's first drive in the next couple of days. This image was taken by one of Curiosity's Navigation cameras on Aug. 21, 2012 (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

After more than two weeks of sitting still, NASA's Mars rover Curiosity is finally set to roll out on the Red Planet with its debut drive on Wednesday.

Engineers successfully tested the rover's steering abilities Monday, Aug. 20, and now they're ready to turn its six wheels for the first time since Curiosity landed on Mars on Aug. 5, officials announced Tuesday.

"Everything's in fine shape, and that means we are 'go' for our first test drive tomorrow," Curiosity mission manager Mike Watkins, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif., told reporters.

Curiosity's first drive on Mars will be a short one. The rover will move about 10 feet (3 meters) forward, turn in place to the right, and then back up a few meters. The whole operation should take the rover about 30 minutes, Watkins said.

Taking it slow

The 1-ton Curiosity rover is the heart of NASA's Mars Science Laboratory mission (MSL), which seeks to determine if the Red Planet could ever have hosted microbial life. The rover is exploring a huge crater called Gale that's about 96 miles wide (154 kilometers) .

Curiosity's main target is the base of Mount Sharp, the 3.4-mile-high (5.5 km) mountain rising from Gale Crater's center. Mount Sharp's foothills appear to bear clays and sulfates, suggesting the area was exposed to liquid water long ago.

But the rover's first big set of drives will take it away from its ultimate destination, toward a spot mission scientists have dubbed Glenelg. Glenelg, which is about 1,300 feet (400 m) from Curiosity's landing site, hosts three different geological formations that mission scientists are eager to investigate.

If all goes well with tomorrow's driving test and a few other checkouts, Watkins said, Curiosity could start heading for Glenelg around Sol 20 or so — mission lingo for its 20th full day on Mars. That corresponds roughly to Saturday (Aug. 25), since Sol 16 begins this evening.

The mission team eventually wants Curiosity to cover about 330 feet (100 m) or more of Martian ground in a big driving day, but that probably won't happen for a while.

"It's going to take us a little while to get up to that rate," Watkins said. "This first set of drives — not just the test drive tomorrow but actually the drive to Glenelg — we'll probably do that in pretty small chunks, just to evaluate, you know, what's going on and take a look at the processing algorithms. My guess is that those are going to go in 10- to 20-meter chunks."

In good shape

Researchers have been checking out Curiosity and its 10 science instruments since the rover landed, ensuring that it's ready for its two-year surface mission.

By and large, the checkouts have been going extremely well, team members have said. On Sunday (Aug. 19), for example, engineers deployed Curiosity's 7-foot-long (2.1 m) robotic arm for the first time and did motor checks on its many tools, which include a percussive drill and soil-scooping gear.

"All of that went successfully as well," Watkins said.

And on Friday (Aug. 17), Curiosity used its Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN) instrument for the first time on Mars. DAN measures the amount of hydrogen — an indicator of water — in the Martian soil by peppering the ground with neutrons and then observing the extent to which they scatter back.

Curiosity's ChemCam instrument — which fires a laser at rocks and then determines their composition by analyzing the vaporized bits — also got its first workout over the weekend. It's performing even better than anticipated, researchers said.

Curiosity's onboard weather station, which is called REMS (short for Rover Environmental Monitoring Station), has been switched on. From Aug. 16 to Aug. 17, it measured ground temperatures as high as 37 degrees Fahrenheit (3 degrees Celsius) and as low as minus 131.8 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 91 degrees Celsius).

However, REMS is not working perfectly on the Martian surface. Wind sensors on one of the instruments' two booms have been damaged, perhaps by rocks deposited on Curiosity's deck during or shortly after landing, researchers said.

But wind sensors on the other boom are working fine, so the team doesn't anticipate too much of an impact.

"We still retain nearly the full capability, just with a little bit of ambiguity in terms of wind direction," said MSL deputy project scientist Ashwin Vasavada of JPL.