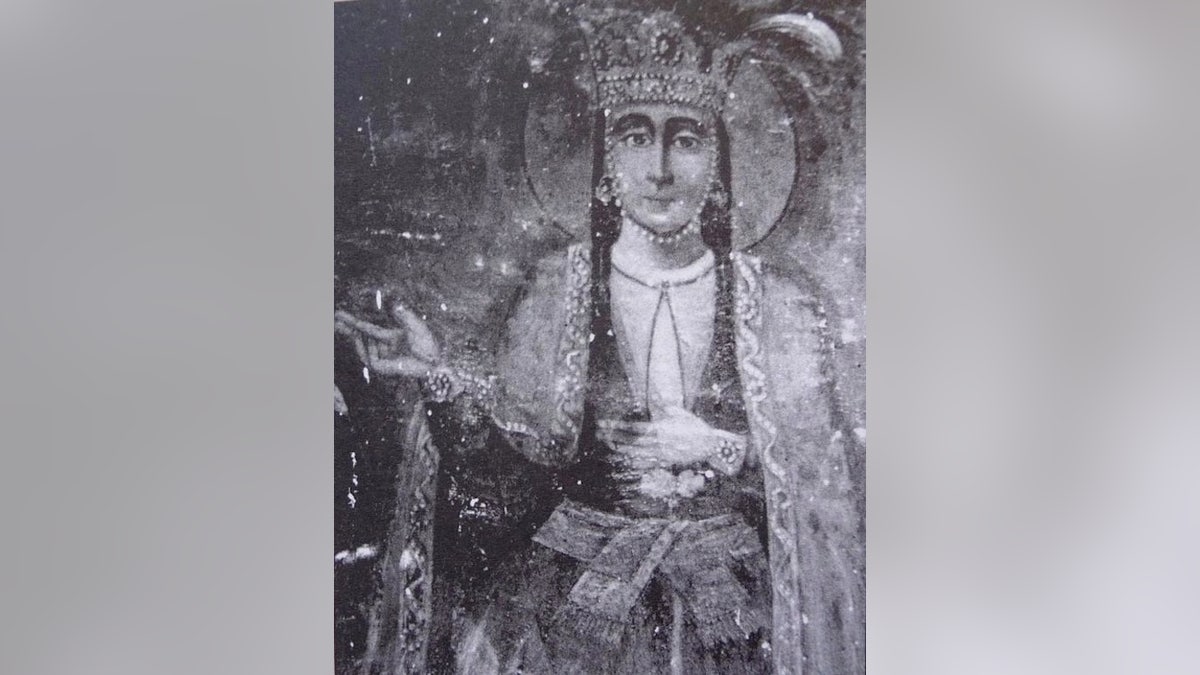

New DNA analysis of a bone fragment found in an Indian Church suggest that the relic belongs to Queen Ketevan, who was martyred in the 1600s. (Wikimedia Commons)

The remains of a woman kept in an Indian church likely belong to an ancient queen executed about 400 years ago, a new DNA analysis suggests.

The DNA analysis suggests the remains are those of Queen Ketevan, an ancient Georgian queen who was executed for refusing to become a member of a powerful Persian ruler's harem. The findings are detailed in the January issue of the journal Mitochondrion.

Tumultuous life

Ketevan was the Queen of Kakheti, a kingdom in Georgia, in the 1600s. After her husband the king was killed, the Persian Ruler, Shah Abbas I, besieged the kingdom.

"Shah Abbas I led an army to conquer the Georgian kingdom and took Queen Ketevan as prisoner," said study co-author Niraj Rai, a researcher at the Center for Cellular and Molecular Biology in Hyderabad, India.

[pullquote]

Queen Ketevan languished in Shiraz, Iran, for about a decade. But in 1624, Shah Abbas asked the queen to convert to Islam from Christianity and join his harem. She refused, and he had her tortured, then executed on Sept. 22, 1624. Ketevan the Martyr was canonized as a saint by the Georgian Orthodox Church shortly after. [Saintly? The 10 Most Controversial Miracles]

Missing relics

Before her death, Queen Ketevan had befriended two Augustinian friars who became devoted to her. Legend had it that, in 1627, the two friars secretly dug up her remains and smuggled them out of the country. An ancient Portuguese document suggested her bones were held in a black sarcophagus kept in the window of the St. Augustinian Convent in Goa, India.

But the centuries had not been kind to the church: Part of the convent had collapsed and many valuables had been sold off in the intervening centuries. Early attempts to find her remains failed.

But starting in 2004, Rai and colleagues excavated an area they believed contained the remains and found a broken arm bone and two other bone fragments, as well as pieces of black boxes.

Rare lineage

To find out if the bones belonged to the martyred queen, the researchers extracted mitochondrial DNA, or DNA found only in the cytoplasm of an egg that is passed on through the maternal line.

The arm bone once belonged to a female with a genetic lineage, or haplogroup, known as U1b, the analysis showed. In a survey of 22,000 people from the Indian subcontinent, the researchers found none with U1b lineage. By contrast, the lineage was fairly common in a sample of 30 people from Georgia.

The other two bones showed evidence they were part of genetic lineages common in India, which supported documents suggesting the queen's relics were stored in a room with the bones of two local friars.

"The complete absence of haplogroup U1b in the Indian subcontinent and its presence in high-to-moderate frequency in the Georgia and adjoining regions, provide the first genetic evidence for the [arm bone] sample being a relic of Saint Queen Ketevan of Georgia," Rai told LiveScience.

The study is well done and honest, Jean-Jacques Cassiman, a geneticist at the University of Leuven in Belgium who was not involved in the study, wrote in an email.

"It is a bone presumed to be of the queen and will remain so until its DNA can be compared to that of preferably living relatives and if not available dead relatives," Cassiman said, referring to nuclear DNA that is in all the body's cells.

But until that point, the conclusion is based on statistics. Those statistics strengthen the idea that the bone belongs to St. Ketevan, but aren't strong enough to positively identify the remnant, Cassiman said.

Copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.