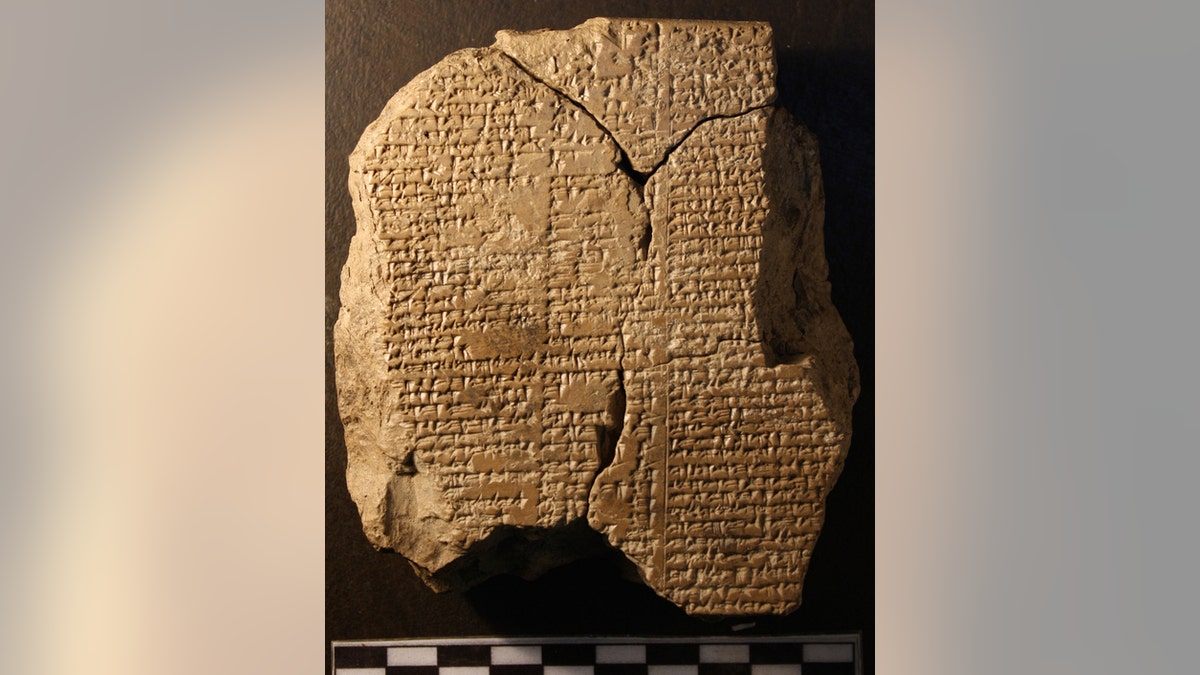

This clay tablet in inscribed with one part of the Epic of Gilgamesh. It was most likely stolen from a historical site before it was sold to a museum in Iraq. (Farouk Al-Rawi)

A serendipitous deal between a history museum and a smuggler has provided new insight into one of the most famous stories ever told: "The Epic of Gilgamesh."

The new finding, a clay tablet, reveals a previously unknown "chapter" of the epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia. This new section brings both noise and color to a forest for the gods that was thought to be a quiet place in the work of literature. The newfound verse also reveals details about the inner conflict the poem's heroes endured.

In 2011, the Sulaymaniyah Museum in Slemani, in the Kurdistan region of Iraq, purchased a set of 80 to 90 clay tablets from a known smuggler. The museum has been engaging in these backroom dealings as a way to regain valuable artifacts that disappeared from Iraqi historical sites and museums since the start of the American-led invasion of that country, according to the online nonprofit publication Ancient History Et Cetera.

Among the various tablets purchased, one stood out to Farouk Al-Rawi, a professor in the Department of Languages and Cultures of the Near and Middle East at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London. The large block of clay, etched with cuneiform writing, was still caked in mud when Al-Rawi advised the Sulaymaniyah Museum to purchase artifact for the agreed upon $800. [In Photos: See the Treasures of Mesopotamia]

With the help of Andrew George, associate dean of languages and culture at SOAS and translator of "The Epic of Gilgamesh: A New Translation" (Penguin Classics, 2000), Al-Rawi translated the tablet in just five days. The clay artifact could date as far back to the old-Babylonian period (2003-1595 B.C.), according to the Sulaymaniyah Museum. However, Al-Rawi and George said they believe it's a bit younger and was inscribed in the neo-Babylonian period (626-539 B.C.).

Al-Rawi and George soon discovered that the stolen tablet told a familiar story: the story of Gilgamesh, the protagonist of the ancient Babylonian tale, "The Epic of Gilgamesh," which is widely regarded as the first-ever epic poem and the first great work of literature ever created. Because of the time period when the story was written, the tale was likely inscribed on "tablets," with each tablet telling a different part of the story (kind of like modern chapters or verses).

What Al-Rawi and George translated is a formerly unknown portion of the fifth tablet, which tells the story of Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, and Enkidu (the wild man created by the gods to keep Gilgamesh in line) as they travel to the Cedar Forest (home of the gods) to defeat the ogre Humbaba.

The new tablet adds 20 previously unknown lines to the epic story, filling in some of the details about how the forest looked and sounded.

"The new tablet continues where other sources break off, and we learn that the Cedar Forest is no place of serene and quiet glades. It is full of noisy birds and cicadas, and monkeys scream and yell in the trees," George told Live Science in an email.

In a parody of courtly life, the monstrous Humbaba treats the cacophony of jungle noises as a kind of entertainment, "like King Louie in 'The Jungle Book,'" George said. Such a vivid description of the natural landscapes is "very rare" in Babylonian narrative poetry, he added

Other newfound lines of the poem confirm details that are alluded to in other parts of the work. For example, it shows that Enkidu and Humbaba were childhood buddies and that, after killing the ogre, the story's heroes feel a bit remorseful, at least for destroying the lovely forest.

"Gilgamesh and Enkidu cut down the cedar to take home to Babylonia, and the new text carries a line that seems to express Enkidu's recognition that reducing the forest to a wasteland is a bad thing to have done, and will upset the gods," George said. Like the description of the forest, this kind of ecological awareness is very rare in ancient poetry, he added.

The tablet, now mud-free and fully translated, is currently on display at the Sulaymaniyah Museum. A paper outlining Al-Rawi and George's findings was published in 2014 in the Journal of Cuneiform Studies.

- Photos: New Archaeological Discoveries in Northern Iraq

- Voynich Manuscript: Images of the Unreadable Medieval Book

- In Photos: Archaeology Around the World

Copyright 2015 LiveScience, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.