The merchant who cut down a swastika flag from a German liner in the 1930s

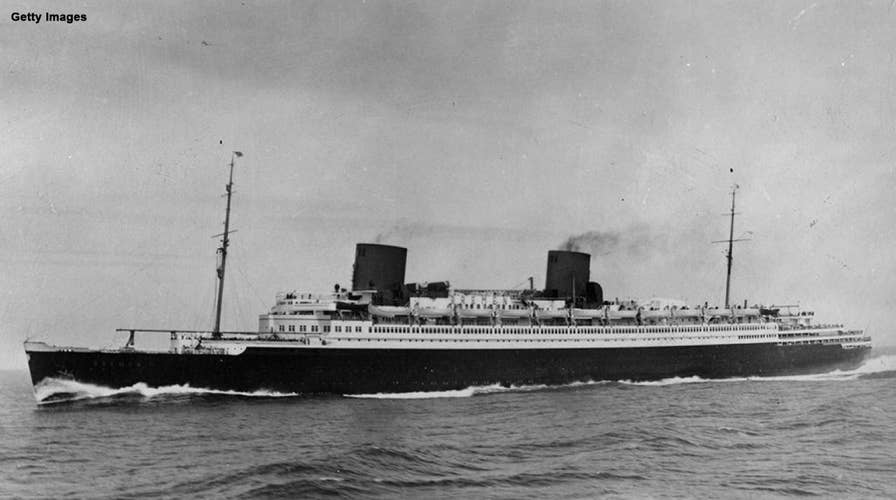

In the 1930s, a luxury German liner called the ‘Bremen’ was an ideal vacation-ready ship, except for the swastika flag flying aboard its bow. But one brave merchant marine devised a plan to cut down the flag and became the first American to take a public stand against Nazi aggression.

In the early 1930s, the Bremen docked regularly on the Hudson River by West 46th Street — and it was a wonder.

The length of three football fields, the ship was built for luxury. Equipped to host 2,200 passengers and 950 crew, with everything from Turkish baths to a library stocked with the world’s finest literature, it was the ideal vacation-ready ocean liner.

The only drawback was the swastika flag flying high aboard its bow.

As the Bremen routinely sailed between Germany and New York, ferrying dignitaries and other wealthy revelers, the horrors of the Nazi regime were leaking out to the world. But too many — including President Franklin Roosevelt — chose to ignore or deny the atrocities at that time.

Yet merchant marine Bill Bailey knew the truth, and his protest against the Bremen would make him the first American to take a public stand against Nazi aggression, writes Peter Duffy in the new book, “The Agitator” (PublicAffairs), out now.

Bailey was born in 1915 in Jersey City. Living in dire poverty with his mother and five siblings, his drunken lout of a father having run off, he sensed early on that the sea would be his escape.

When he was 14, he visited every pier on the Hudson River until the captain of an old freighter agreed to take him on.

NAZI LABOR CAMP GUARD CAUGHT BY ICE, DEPORTED TO GERMANY, COMPLETING 'DIFFICULT TASK'

“I stood there lying like hell,” Bailey later said. “Told him I was an experienced seaman, been on all seven seas including the Dead Sea. I could do anything on a ship, blah, blah, and I’m 21 years old … And the guy just said, ‘Yeah, OK.’ And from then on, I had a job as an ordinary seaman.”

Working on various ships throughout the years, Bailey saw the world for real. In 1932, he ended up in Germany, where he got a rare up-close look, for an American, at the encroaching Nazi horror.

“Bailey was inspired by the fighting spirit of the Communist longshoremen … and outraged by the brutality of Nazi storm troopers, who were already running all over Germany, punching people out, kicking windows in, attacking Jews,” Duffy writes.

Flagship ceremony on Bremen in the port of New York. After the Reichsflaggengesetz adopted by the Reichstag, the German merchant flag was replaced by the Nazi flag. Photo by ullsteinbild via Getty Images)

Those experiences abroad colored Bailey’s politics. In 1933, he was 18 and between jobs in New York, when he joined the Marine Workers Industrial Union. He began speaking publicly, recruiting union members among the dockworkers. He also became a member of the Communist Party.

By 1935, the Bremen was a popular attraction in the city. Whenever it docked to discharge passengers from Germany and take on new ones for the return trip, several thousand New Yorkers were allowed on board for a fee to party for one night. At night’s end, a horn would blow, urging visitors off the ship.

By then, many New Yorkers were aware of Germany’s atrocities, and the Bremen was increasingly met with thousands of protestors who felt Hitler’s prized vessel should not be welcomed to our shores, much less be used to dine and dance. As authorities continued to allow it to dock, Bailey and his fellow party members decided to do something to “wake this goddamn United States up,” Bailey later wrote.

With the Bremen due in New York again on July 26, 1935, the leaders of Bailey’s Communist Party branch came up with a plan. As protests were already expected on the street below, several dozen party members — male and female — would dress in their finest eveningwear and board the boat like revelers. When the horn blasted, telling non-passengers to leave the boat, several of the women would handcuff themselves to the ship’s mast and create a distraction. Then, the men would seize the swastika flag and march it off the boat to the party chairman, who would set fire to it in the street.

At first, the role of capturing the flag fell to one of the party’s longest-serving members, 36-year-old Merchant Marine Edward Drolette.

But Drolette “couldn’t keep his mouth shut,” and the plan got leaked to the NYPD. When Drolette boarded the Bremen sometime after 10:30 p.m., police were on his tail. By that point, the ship was in full-on party mode, with passengers including Henry S. Morgan, grandson of J.P. Morgan and future founder of Morgan Stanley, and William Donner Roosevelt, “the 2-year-old grandson of the president of the United States.”

Meanwhile, Bailey and two fellow Communists, Mac Blair and Paddy Gavin, wandered the deck toward the flag, “occasionally barking out a ‘Sieg Heil’ for appearance’s sake.”

By 11:15 p.m., the NYPD notified the Bremen’s owners that infiltrators had breached their security, and the ship’s commander “issued an order seeking the removal of all visitors.” But the 4,800 people on board made that impossible while also blocking Drolette’s starboard path to the flag.

So the infiltrators changed their plan, and agreed that Bailey, Blair and Gavin would capture the flag from port side instead.

At 11:45 p.m., the ship’s horn blew, encouraging visitors to leave. In the melee, the handcuff plan was abandoned, but one lone Communist protestor marched toward a restricted portion of the deck.

When a Bremen crew member barked a rebuke, the rebel wound up his fist and “lobbed a haymaker that knocked the man flat on his back.”

Chaos took hold, and Blair and Bailey seized their moment.

Bailey slipped past the authorities, but Blair felt a hand on his neck. Seeing it belonged to a Nazi crew member, he turned and stabbed him in the face with a fountain pen. Bailey paused to help, but Blair urged him on.

“Keep going!” he yelled. “Get up there!”

Leaping aboard the ship’s gunwale with police nightsticks swinging around him, Bailey began to climb a flimsy ladder.

With “a roar of triumph” rising around him from the thousands of protestors on the street, Bailey reached for his target.

“Feeling ‘almost stage fright,’ Bailey took a moment to glance down,” Duffy writes. “Without a rail to brace himself, he understood that the slightest misstep would put him in the drink. He tugged at the swastika, which ripped along the top seam.” But he couldn’t get the bottom half of the flag to move.

As he struggled, one of his comrades pulled out a switchblade and cut the rope holding the flag. Suddenly the swastika fell loose and was now fully in Bailey’s hands.

It was now or never.

“Bill Bailey hurled Hitler’s treasure into the Hudson River,” Duffy writes. “The swastika came sliding down, disappeared a moment, ballooned up and went skimming through the air dropping into the water below.”

Said Bailey later of his triumph: “It was a moment worth everything … just to see that sonofab***h in the water and the Germans going stark mad! And the crowd on the dock stark mad with delight.”

Afterwards, a State Department spokesperson issued an apology to Germany before one was even requested, saying, “It is unfortunate that two or three persons should mistreat the flag of any nation with which the United States is at peace.”

Bailey, Blair, Drolette and three of their co-conspirators were arrested and dubbed “The Bremen Six” in the press, which at the time firmly took the side of the Nazis. They were charged with felonious assault on a police officer and intent to breach the peace, but after long, high-profile trials, all six were acquitted.

The Bremen, meanwhile, continued its New York to Germany route, with a new swastika flag flying high until September 1939, when Great Britain declared war on Germany and it returned home for good. The ship was destroyed in an attack by the British Royal Air Force and sold off for scrap metal.

In the postwar years, Bailey was destroyed as well, getting caught in the Red Scare of the time, blacklisted and kicked out of the Marine Workers union for being a Communist in 1950. Six years later, Bailey quit the Communist Party himself, because he realized that Stalin was a “paranoid, sick SOB.”

He spent the next few decades as a longshoreman and activist in San Francisco where he gave radical walking tours of the city and reemerged as a father figure to other liberal organizers. Robert De Niro even relied on Bailey’s experience on the blacklist for his 1991 film “Guilty by Suspicion,” in which the old seaman had a walk-on role as a security guard.

Bailey suffered from a lung condition caused by asbestos exposure from his work on the high seas. But even that didn’t dim his passion until his death in 1995, age 79.

“To witness an injustice and do nothing,” he once said. “That is the biggest crime.”

This story originally appeared in the New York Post.