Liang Bua, a limestone cave on the Indonesian island of Flores. The Liang Bua Team prepares for new archaeological excavations. (Smithsonian Digitization Program Office / Liang Bua Team)

It turns out a tiny hominin nicknamed the “Hobbit” may have disappeared from the Indonesian island of Flores much earlier than scientists originally thought.

When it was first discovered in 2003 in the Liang Bua cave, an international team concluded that H. floresiensis was 18,000 years old and bone fragments were deposited there from 12,000 and 95,000 years ago. But after digging up new stratigraphic and chronological evidence from other parts of the massive, stalactites, filled cave, scientists concluded in a Nature study published Wednesday that new dates for the tiny creature – that stood only 3.6 feet and had a chimp-sized brain - range from 190,000 to 50,000 years ago.

The remains of H. floresiensis _ including 20-foot skeleton and bone fragments of as many as 10 individuals – have been dated from between about 100,000 and 60,000 years old. Stone artifacts found in the cave and believed to have been used by the hobbit range from 190,000 years to 50,000 years.

Related: When the 'Hobbits' Conquered Indonesia

The new dates are significant because it reduces the possibility – although it doesn’t eliminate it – that H. floresiensis came in contact with modern humans who were most likely traveling from Asia to Australia. Modern humans are believed to have reached Australia 50,000 years ago and the earlier dates – also from stone tools in the cave - raised the prospect that humans clashed with H. floresiensis and competed for resources.

“We dated charcoal, sediments, flowstones, volcanic ash and even the H. floresiensis bones themselves using the most up-to-date scientific methods available. In the last decade, we’ve vastly improved our understanding of when the deposits accumulated in Liang Bua, and what this means for the age of ‘hobbit’ bones and stone tools,” Richard ‘Bert’ Roberts, an Australian Research Council Laureate Fellow at the University of Wollongong who oversaw the various dating analyses used in the study, said in a statement.

“But whether ‘hobbits’ encountered modern humans or other groups of humans—such as the ‘Denisovans’—dispersing through Southeast Asia remains an open and intriguing question,” he added.

Matthew Tocheri, the Canada research chair in human origins at Lakehead University and a co-author on the study, said a priority is finding evidence that modern humans and H. floresiensis overlapped on Flores. So far, the earliest evidence of modern humans on Flores goes back to 11,000 years.

Related: Humans, Neanderthals interbred thousands of years earlier than first thought, research shows

“With the new dating results pushing back that last appearance time of H. floresiensis to 50,000 years ago, it certainly removes the potential amount of time overlap on the island itself,” Tocheri, who is also a research associate at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, told FoxNews.com

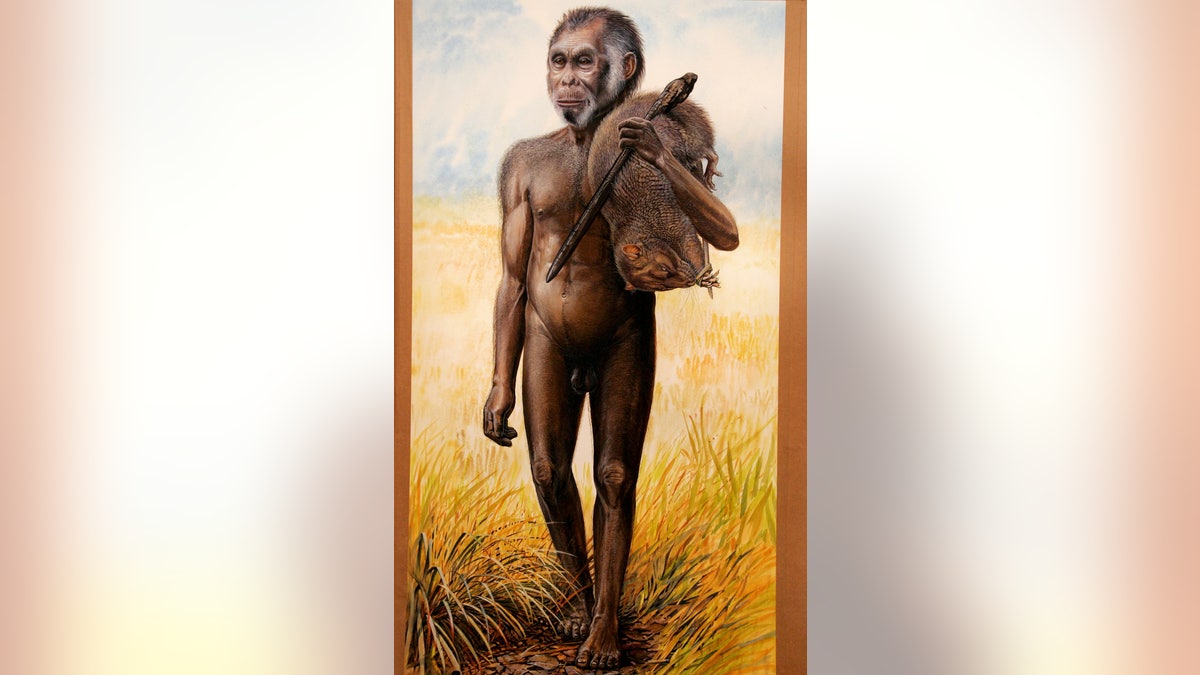

An artist's drawing sits on display at the Australian Museum in Sydney October 28, 2004 of a newly discovered species of hobbit-sized humans that adds another piece to the complex puzzle of human evolution. (REUTERS/HO/Peter Schouten-National Geographic Society)

“But we still don’t have evidence of modern humans on Flores until about 11,000 years ago. It’s clearly a major research question that we are now focused on,” he continued. “There should be remains of modern humans somewhere on Flores that are earlier than that. Modern humans just didn’t jump over the islands of Southeast Asia to get to Australia by 50,000 years ago. They must have come through islands of Indonesia and it’s highly unlikely they skipped Flores.”

But even if modern humans did overlap H. floresiensis, Tocheri said it doesn’t mean they killed off their tiny ancestor. Noting that many other species on the island including Komodo dragons, vultures and pygmy stegodon also disappeared around 50,000 years, Tocheri said a number of factors including increased volcanism and changing climate could also have played a role.

Related: Ancient DNA reveals bones in Spanish cave were Neanderthals

“During the late Pleistocene, there are lots of ice ages going on and off and the climate changing around every few tens of thousands of years,” he said. “There are lots of large animals around the world that go extinct at this time. You look at the Komodo dragon, giant marabou stork, the vulture, pygmy stegodon and the hobbit. They would have been a lot more sensitive to these late Pleistocene climatic shifts.”

Chris Stringer, research leader in human origins at the Natural History Museum in London, said the new dates for are H. floresiensis are “much more in line” with the “inferred last appearances of the Neanderthals and perhaps also the Denisovans.”

“This in turn may reinforce the idea that the successful spread of modern humans from Africa after about 60,000 years ago played at least a role, if not the most significant role, in the physical extinction of other forms of humans outside of Africa,” he said in an email interview. “However, at least some of those other forms of human did not go completely extinct, since their DNA lives on in us today through ancient interbreeding between the archaic and early modern populations. This leaves open the fascinating possibility that even floresiensis might have contributed some of its DNA to living groups in the region, if there was at least a short overlap between floresiensis and sapiens about 50,000 years ago.”

Thomas Sutikna, a co-author on the study also from the University of Wollongong and National Research Centre for Archaeology in Indonesia, said in a statement that dating mix up occurred because “we didn’t realize during our original excavations that the ‘hobbit’ deposits near the eastern wall of the cave were similar in age to those near the cave center, which we had dated to about 74,000 years ago.”

Related: Neanderthal DNA may influence modern depression risk

Archaeological excavations of Holocene deposits at Liang Bua in progress. These sediments contain skeletal and behavioural evidence of modern humans (Homo sapiens). (Liang Bua Team)

As the team expanded their excavation of the cave, Sutikna said it “became increasingly clear that there was a large remnant pedestal of older deposits truncated by an erosional surface that sloped steeply toward the cave mouth” - that was covered by younger sediments over the past 20,000 years.

“Unfortunately, the ages of these overlying sediments were originally thought to apply to the ‘hobbit’ remains, but our continuing excavations and analyses revealed that this was not the case,” said co-author Wahyu Saptomo, head of conservation and archaeometry at the National Research Centre for Archaeology.

But the researchers were adamant that the new dates did little to change their belief – and that of most scientists – that H. floresiensis was still a distant relative, not a deformed modern human as critics have long contended. Those critics argue that the small size of H. floresiensis would indicate it suffered from a genetic disorder that caused the body and brain to shrink.

“For the few stragglers that are still hanging onto (to the idea) that this is a pathological modern human, it certainly weakens their argument yet again,” Tocheri said, comparing those minority voices who believe it’s a modern human to scientists who “say that human-mediated climate change isn’t happening right now" or "that smoking doesn’t cause cancer.”

“The field has really shifted to debates over these more interesting questions of what is H. floresiensis descended from? What is its exact relationship to us?” he added.

Stringer agreed.

The dates “would seem to fatally undermine remaining claims that the ‘Hobbit’ fossils belong to diseased modern humans, since the material now dates beyond any modern human specimens known from the region,” he said.“That said, my guess is that the sceptics will still not back down, as they have shown no signs of doing so in the face of a wealth of other data that conflict with their ideas.”