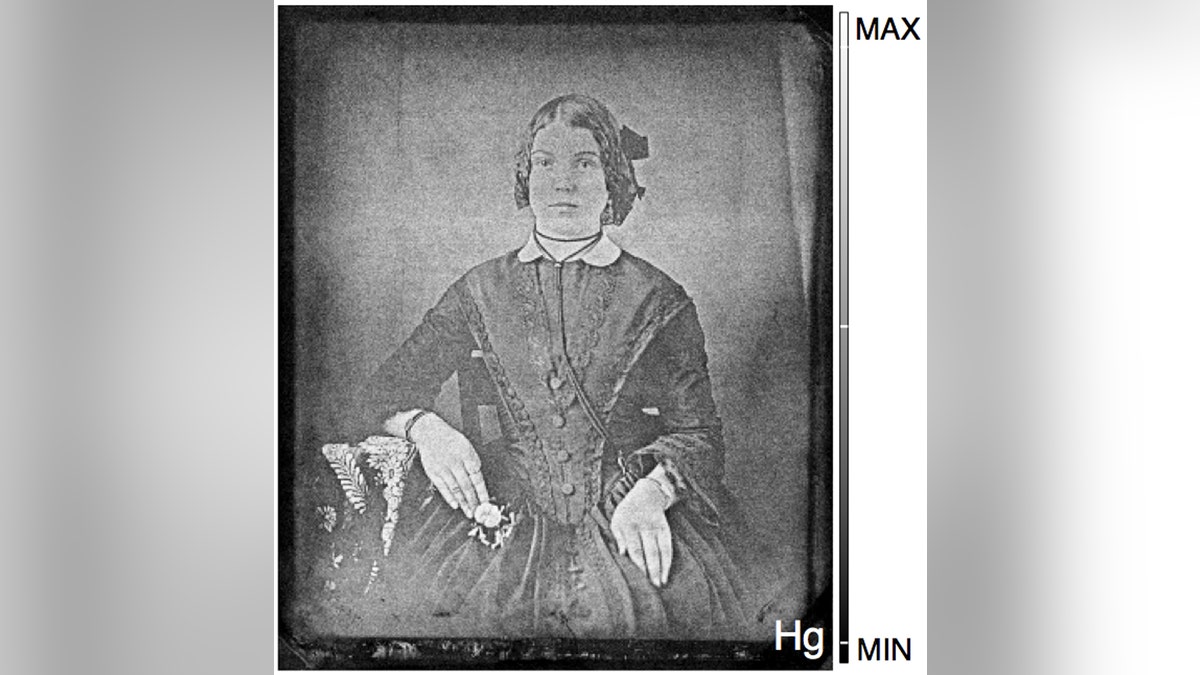

An image of a woman is recovered from a 19th-century daguerreotype that had tarnished almost beyond recognition. With the novel process, researchers mapped its mercury content and brought the 'ghost' back to life. (Credit: National Gallery of Canada/Western University)

If there's something strange going on in your neighborhood, it might be a better idea to call a photographer than a ghostbuster.

A novel process developed at Western University and Canadian Light Source Inc. is allowing researchers to recreate photographs from the 19th century, thought to have been lost forever.

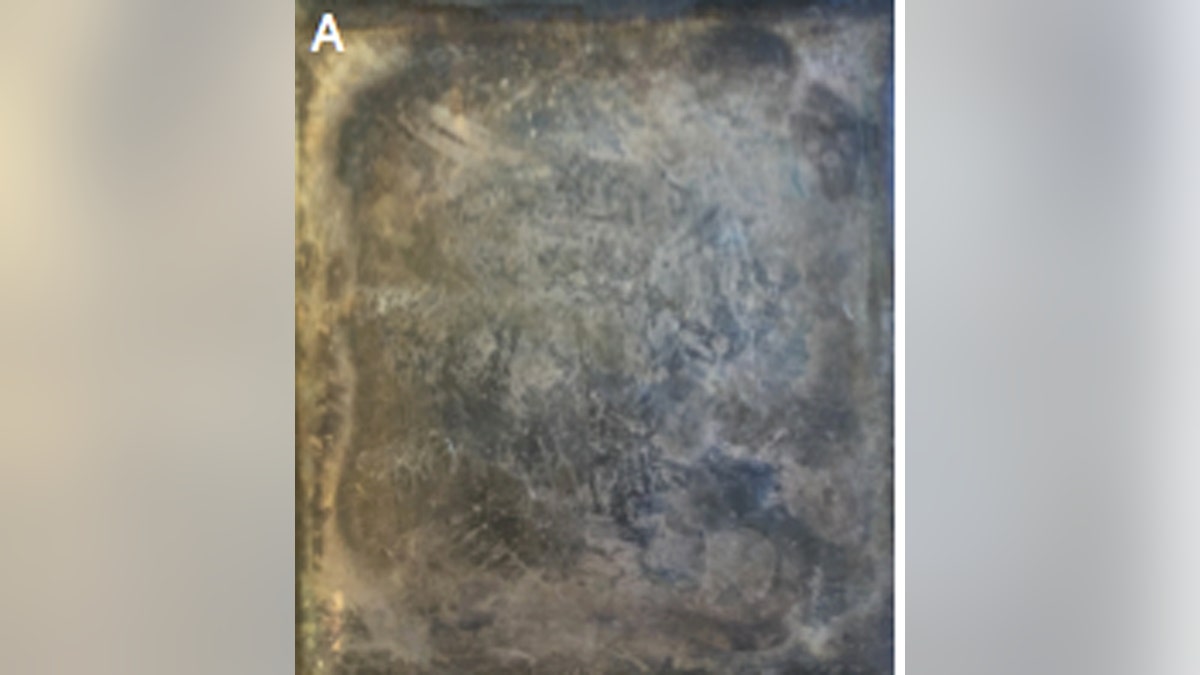

The technique utilizes the unique composition of the photographs, known as daguerreotypes, to digitally recreate the original image that had been discolored and decayed to the point it had become completely unrecognizable.

“It’s somewhat haunting because they are anonymous and yet it is striking at the same time,” Madalena Kozachuk, a PhD student in Western’s University Department of Chemistry and lead author of the scientific paper, said in a statement.

NEVER-BEFORE-SEEN COLD WAR VIDEOS DECLASSIFIED

(National Gallery of Canada/Western University)

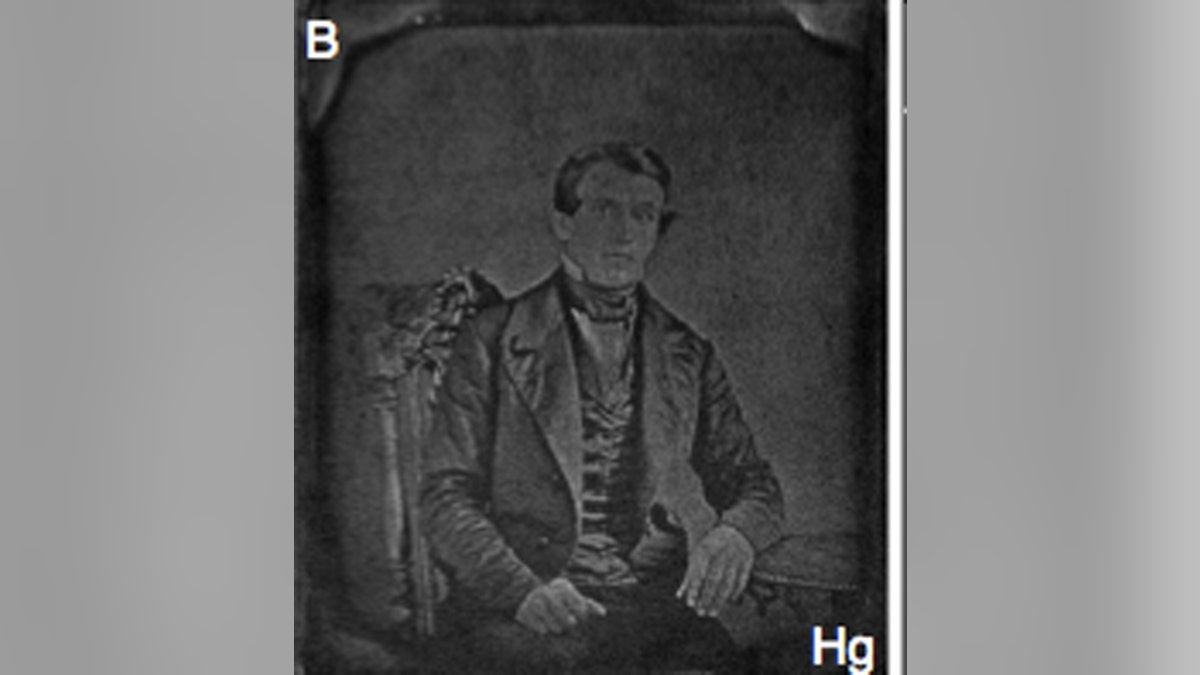

Kozachuk, who worked on two portraits, said the images that appeared were unexpected because they were not seen on the silver-coated copper plates.

“The image (...) is hidden behind time,” he said, "but then we see it and we can see such fine details: the eyes, the folds of the clothing, the detailed embroidered patterns of the table cloth.”

(National Gallery of Canada/Western University)

It's unclear who the man and the woman are in the photos; it's also unclear when the photos were taken (Kozachuk suspects they could be from as early as 1850, but was not sure) or where they were taken.

Kozachuk told LiveScience that the photo of the woman had been purchased at a garage sale but did not know where the photo of the man came from.

The research findings were published in the journal Scientific Reports last month.

Daguerreotype photographs were created in 1839 by Louis Daguerre, a French artist and photographer, and one of the fathers of modern-day photography.

(National Gallery of Canada/Western University)

Daguerreotypes used silver plates and created images using an iodine vapor that formed a compound that darkened when exposed to light. After the subject had been in place for a few minutes, the image was imprinted on the plate and could be turned into a photograph using heated mercury vapor. It was then treated with a sodium bithiolate solution and covered with a glass plate to be preserved, Kozachuk explained in her statement.

Kozachuk and her team used a technique known as synchrotron technology, while using "rapid-scanning micro-X-ray fluorescence imaging to analyze the plates." They were able to identify where the mercury was on the plates and found that even though the surface had been tarnished, the images were still intact.

COLONIAL ERA MICHIGAN FORT REVEALS ITS SECRETS

“We compared degradation that looked like corrosion versus a cloudiness from the residue from products used during the rinsing of the photographs during production versus degradation from the cover glass," Ian Coulthard, a co-author on the study, said in a statement. "When you look at these degraded photographs, you don’t see one type of degradation.”

"Even though the surface is tarnished, those image particles remain intact," study co-researcher Tsun-Kong (T.K.) Sham added in the statement. "By looking at the mercury, we can retrieve the image in great detail."

Kozachuk said that there were "no expectations" going into the project, but the end results were promising. "The first image we saw was of the woman's face," she told LiveScience. "I think I squealed. It was extremely exciting."

Follow Chris Ciaccia on Twitter @Chris_Ciaccia