Fox News Flash top headlines for Dec. 17

Fox News Flash top headlines for Dec. 17 are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com

If there is life in the Solar System outside of Earth, Jupiter's moon Europa and Saturn's moon Enceladus are two of the most likely spots to hold them.

However, any extraterrestrial creatures on these celestial objects probably are not related to us, according to a new study.

The research, presented at the annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union by Purdue University geophysicist Jay Melosh, looked at the idea of "lithopanspermia," an idea that life hopped from one planet to another via rocks that were ejected into space, according to Space.com, which first reported the news.

In 100,000 simulated ejections from Martian particles, Melosh found that a tiny fraction of these rocks — 0.0000002 percent to 0.0000004 percent for Enceladus and 0.00004 percent to 0.00007 percent for Europa — ended up hitting these moons. He used three different ejection speeds in his simulations: 1, 3 and 5 kilometers per second.

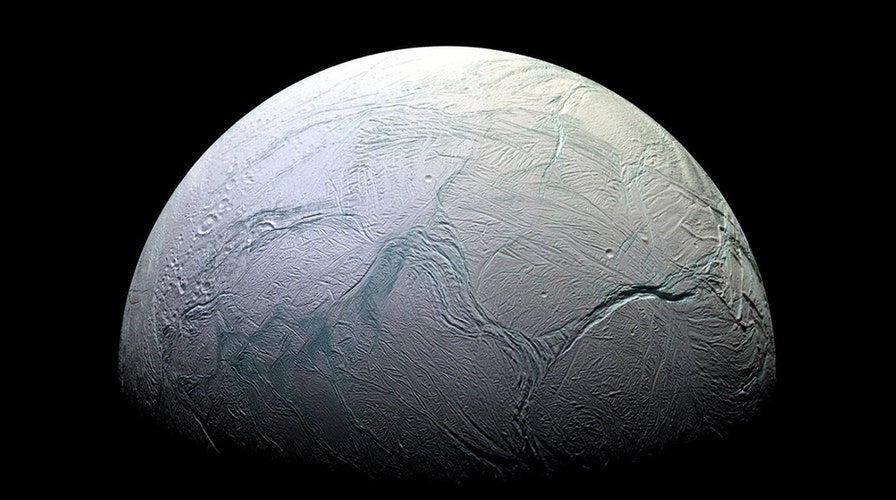

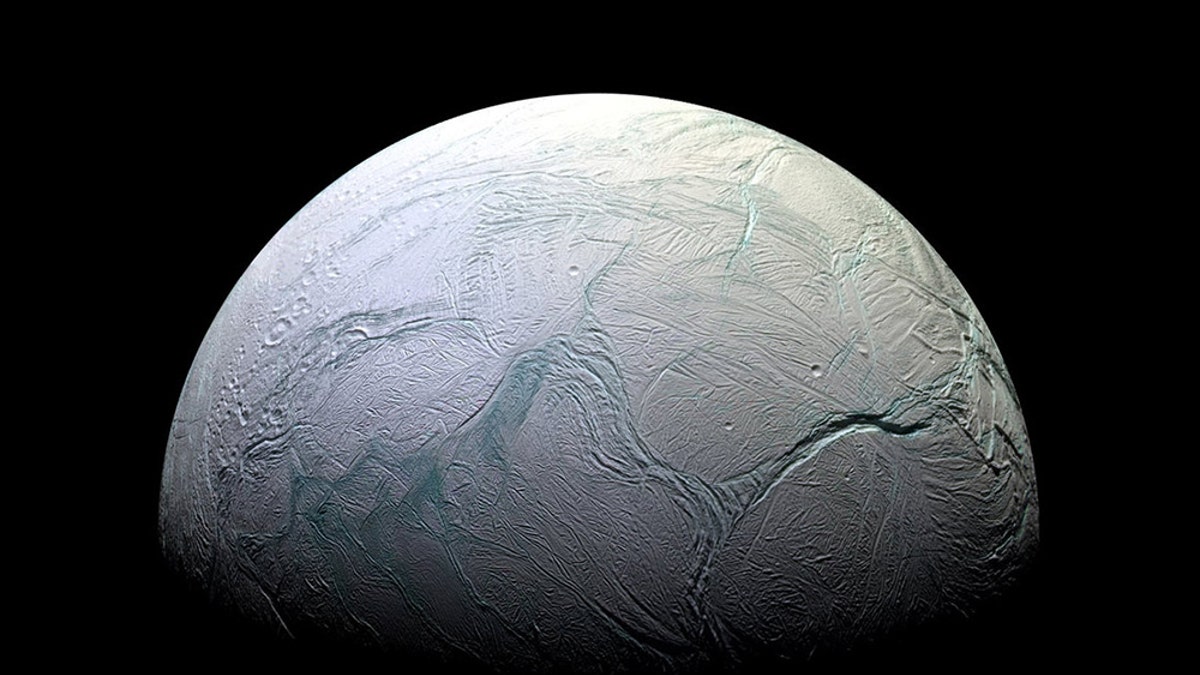

With its global ocean, unique chemistry and internal heat, Enceladus has become a promising lead in our search for worlds where life could exist. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

NASA DETECTS WATER VAPOR ON JUPITER'S MOON EUROPA

Lithopanspermia is similar to panspermia, the hypothesis that life on Earth originated from microorganisms in outer space that were carried here unintentionally by objects such as space dust, meteoroids and asteroids, according to an article on NASA's website.

Using the baseline that approximately 1 ton of Martian rocks hit Earth ever year, Melosh estimated that Europa sees an average of approximately 0.4 grams of Martian material and just 2 to 4 milligrams for Enceladus.

"So, the bottom line: If life should be found in the oceans of Europa or Enceladus, it is very likely that it’s indigenous rather than seeded from Earth, Mars or (especially) another solar system," Melosh said during the conference, according to Space.com.

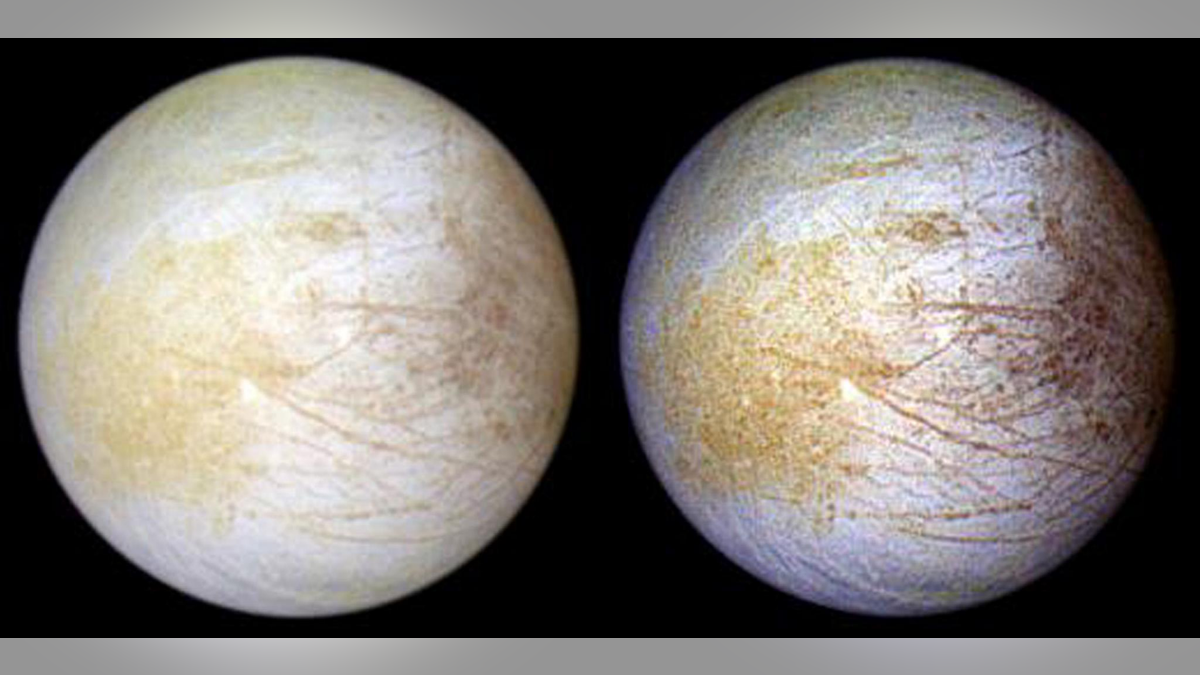

NASA’s Galileo spacecraft captured this color composite view of the Jupiter moon Europa in 1997. (NASA/JPL/University of Arizona)

ALIEN LIFE ON SATURN'S MOON? DUST STORMS ON TITAN SPOTTED FOR THE FIRST TIME

Melosh added that it takes approximately 2 billion years for a meteorite from Mars to hit Enceladus. If there were living organisms on these Martian space rocks, it's possible they could survive if the speed was at the lower end of the range he put forth, but if the speeds were higher, survival would be difficult to imagine, he added.

In June, NASA said it would send a mission to one of Saturn's other moons, Titan, which could also be home to life. Launching in 2026, the mission, known as Dragonfly, will see a rotorcraft fly "to dozens of promising locations" on Titan after it arrives in 2034.

Two months later, NASA confirmed it would launch a mission to Europa, a trek that could answer whether the icy celestial body could be habitable for humans and support life.