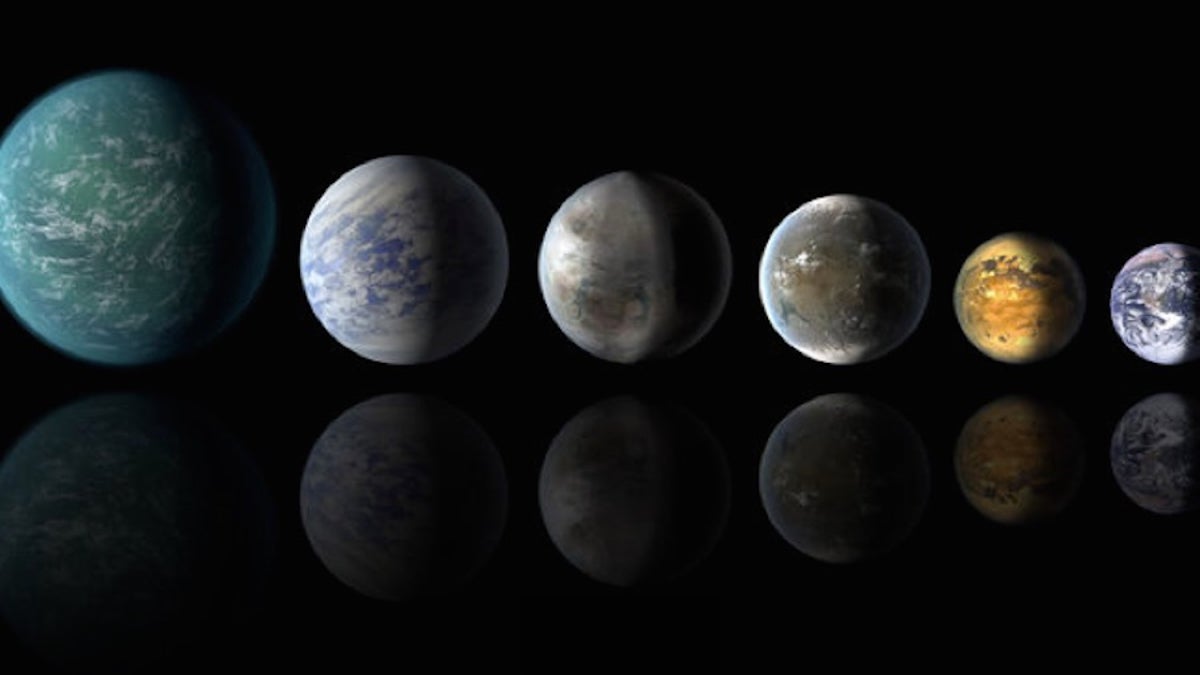

File photo. (NASA/Ames/JPL-Caltech)

When it comes to science, exoplanets are easy to love. They play roles in most science fiction books and movies and spark the imagination of nearly everyone. Beyond the realm of fiction, understanding these worlds remains a significant challenge that astronomers are working hard to overcome.

As 2015 winds down, we caught up with noted exoplanet scientist Sara Seager, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, at the American Astronomical Society's Extreme Solar Systems III conference in Hawaii to ask her perspective on the field over the past year. She pointed to the progress made in understanding rocky worlds and the significant strides made in capturing images of planets. The biggest steps, however, came in the slow progress made in better understanding how planets — both inside and outside of the solar system — are built, she said.

"We really want to know how planetary systems form. It's very complicated, because there are so many different pathways," Seager said. [Related: The Biggest Astronomy Discoveries of 2015]

A series of small steps

Seager said one of the biggest recent advances is the increased ability of scientists to measure the masses of small planets. While many Jupiter-size worlds have masses that can be measured due to the technique used to spot them, most of the planets found by NASA's Kepler mission have only a known radius. Follow-up studies with other instruments have allowed astronomers to obtain the masses of these worlds in some cases, providing the density. Knowing whether an exoplanet has a density closer to rock or gas can help scientists get an idea of that world's possible compositions.

"It looks like anything bigger than 1.6 Earth radii is not rocky," Seager said. (One Earth radius is about 3,863 miles, or 6,378 kilometers.)

Seager also pointed out that the methods used to find and study exoplanets continue to improve.

"Each planet-finding technique took one to two decades to come to maturity," she said.

Of these, the process of directly imaging a planet has made the greatest strides recently. One of the biggest challenges with the technique is in spotting the glow of a planet amid the far brighter light of a star. The farther away a planet lies from its sun, the easier that world is to identify. This makes the technique complementary to searches performed by NASA's Kepler mission, which more easily studies worlds orbiting close to their stars.

"You could say they've been doing direct imaging forever, because people imaged binary stars, but now they're able to see a fainter and fainter companion closer and closer to a hot star," Seager said.

"They're still really far from seeing Earths, but they're definitely making strides."

She estimated that direct imaging should be able to identify an Earth-like world within the next decade.

Hot Jupiter findings heat up

Another major highlight of the year is an improved understanding of the massive, short-orbiting planets known as hot Jupiters. These massive worlds orbit their suns in days or even hours, despite being far larger than Jupiter. The huge planets made up the bulk of the first exoplanet discoveries, yet scientists are still struggling to understand how these worlds formed and why they orbit so close to their suns.

"In exoplanets, there are a million little puzzles," Seager said. "Hot Jupiters appeared not to have any companions initially, but it's because we couldn't really search the set of orbits where planets could live" that we didn't see any companions.

Recent results have shown that hot Jupiters aren't all loners after all. Several of these hot, massive planets turned out to have companions, which Seager said she finds exciting. Some of those are massive rocky bodies far larger than Earth, known as super-Earths.

"One of the original predictions said all hot Jupiters would have an interior super-Earth," she said.

Although a handful of scientists think that hot Jupiters may have originally formed near their parent stars, most researchers think that the gas giants formed farther away, in the same region gas giants of Earth's solar system lie. The planets then migrated inward. As they did so, Seager said, they shepherded any inner planets along with them, scientists think. The recent discoveries that some of these gas giants have companions suggests that, at least in some cases, that hypothesis may hold true.

"Nature probably can move planets around every possible way we can think of and more, so maybe that theory is right," Seager said.

Strange new worlds ahead

Although she couldn't name any single major events for the year that were surprising, she pointed out that understanding how planetary systems tick takes time. The biggest strides in the field this year seem to be the slow gathering of information to allow scientists to begin to put it all together.

"I think one of the big things happening is just the emergence of all of these different clues in different ways," Seager said.

It takes the right person to put it all together, but Seager said that probably will take another decade or so.

That doesn't mean scientists are ready to say they conclusively know how worlds form, a question that has plagued researchers for decades, she said.

"There's no final story now. We can't say, 'Oh, now we understand all planet formation.' That will be decades if not a century or more."