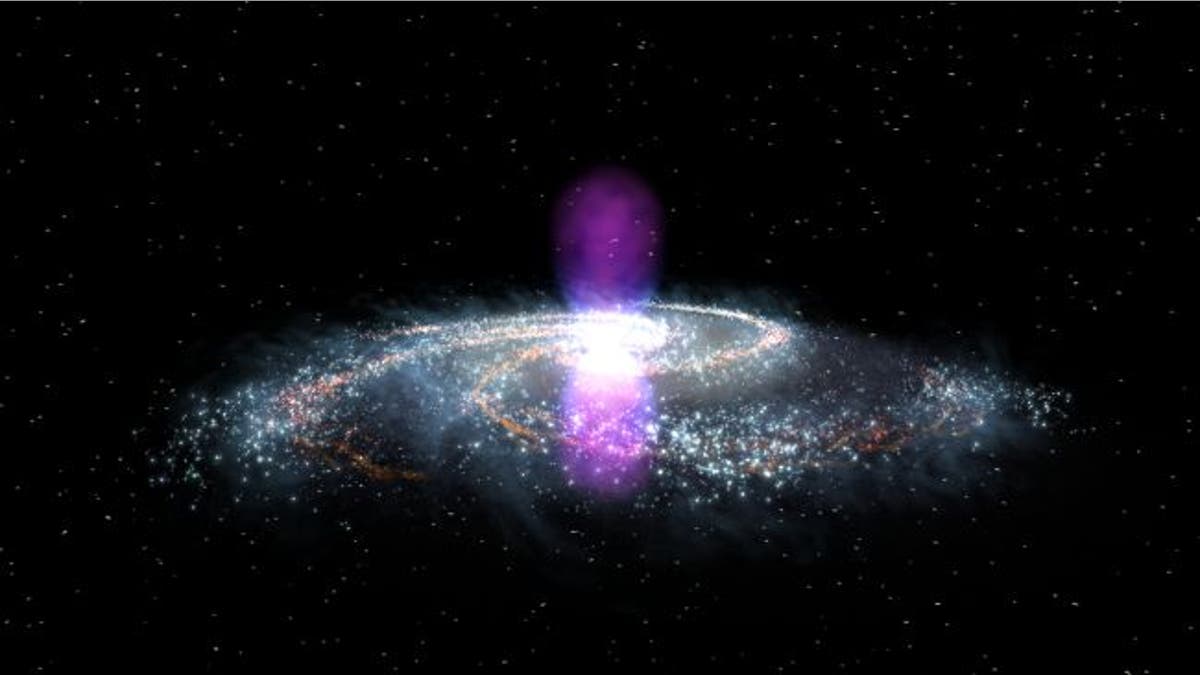

The Fermi bubbles, illustrated in gamma-ray light here, tower over the Milky Way and speak to a gargantuan cosmic explosion from the center of our galaxy. New research attempts to pinpoint that explosion's date. (Credit: NASA Goddard)

At the center of our galaxy is a supermassive black hole which, apparently, likes to blow bubbles.

Ballooning out of both poles of the galactic center, two gargantuan orbs of gas stretch into space for 25,000 light-years apiece (roughly the same as the distance between Earth and the center of the Milky Way), though it's visible only in ultra powerful X-ray and gamma-ray light. Scientists call these cosmic gas orbs the Fermi bubbles and know that they're a few million years old. What caused this bout of galactic indigestion, however, is one of our galaxy's biggest mysteries.

Now, by looking for evidence of this violent bubble-blowing event in the scorched clouds of gas in one of the Milky Way's satellite galaxies, researchers have reconstructed a plausible explanation for the bubbles' birth. According to a study to be published Oct. 8 in the preprint journal arXiv.org, the Fermi bubbles were created by an epic flare of hot, nuclear energy that shot out of the galaxy's poles roughly 3.5 million years ago, beaming into space for hundreds of thousands of light-years. Related: Gargantuan 'Bubbles' of Radio Energy Spotted in the Milky Way

The effect would have been sort of "like a lighthouse beam" that shone out of our galaxy's middle for 300,000 years, lead study author Joss Bland-Hawthorn, director of the Sydney Institute for Astronomy at the University of Sydney, told Live Science in an email. And, given the recent (cosmically speaking) date of the explosion that Bland-Hawthorn and his team calculated, the blast may even have been visible to early humans.

"It's an amazing thought that, when cave people walked the Earth, if they'd looked off in the direction of the galactic center, they'd have seen some kind of giant ball of heated gas," Bland-Hawthorn said in a video accompanying the study.

Pieces of flare

To date the explosion, the researchers looked to Hubble Space Telescope observations of the Magellanic Stream, a 600,000-light-year-wide arc of gas trailing behind two dwarf galaxies that orbit the Milky Way (known as the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds). From our vantage point on Earth, the Magellanic Stream spreads across half of the night sky as it surges through space some 200,000 light-years away.

That's far away, but still close enough for neighboring galaxies to feel the heat of any particularly violent eruptions from our galaxy's central black hole, according to the researchers. Indeed, while most of the hydrogen gas that makes up the Magellanic Stream is very cold, recent Hubble observations have revealed at least three large regions where the gas is unusually hot. Those regions, incidentally, align with the north and south poles of the Milky Way's galactic center. According to Bland-Hawthorn, that’s a clear sign that those hot regions were toasted by an enormous flare-up of charged particles beaming out of our galaxy and into deep space.

"This can only be done radiatively from the monster at the galaxy's nucleus," Bland-Hawthorn told Live Science in an email.

Using mathematical models, Bland-Hawthorn and his colleagues showed how such an explosion of energy — known as a Seyfert flare, a type of outburst that may occur in galaxies with active black holes every 10 million years or so — could blast out of the galactic center and reach all the way to the hottest regions of the Magellanic Stream. They calculated that, in order to reach those affected parts of the stream, the explosion must have occurred between 2.5 and 4.5 million years ago — a time when human early ancestors were already walking the Earth.

While those primitive human ancestors may have seen the mysterious flare overhead, it's unlikely that they were impacted by its energy, thanks to Earth's protective atmosphere, Bland-Hawthorn said. That's good news for us, he added; Seyfert flares occur somewhat randomly in galaxies like ours, and previous research suggests that there may be others on the way.

"It's plausible that one explosion took place 10 million years ago, and the jet is now arriving in our direction," Bland-Hawthorn told Live Science, adding that flares can get trapped in the immediate vicinity of the black holes that made them for millions of years. "But I think the most powerful bursts from our Sun would be about the same power — so, bad for satellites and space walkers, but our atmosphere protects life pretty well."

The team's study will appear in a future issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

- The 12 Strangest Objects in the Universe

- 15 Unforgettable Images of Stars

- 9 Strange Excuses for Why We Haven't Met Aliens Yet

Originally published on Live Science.