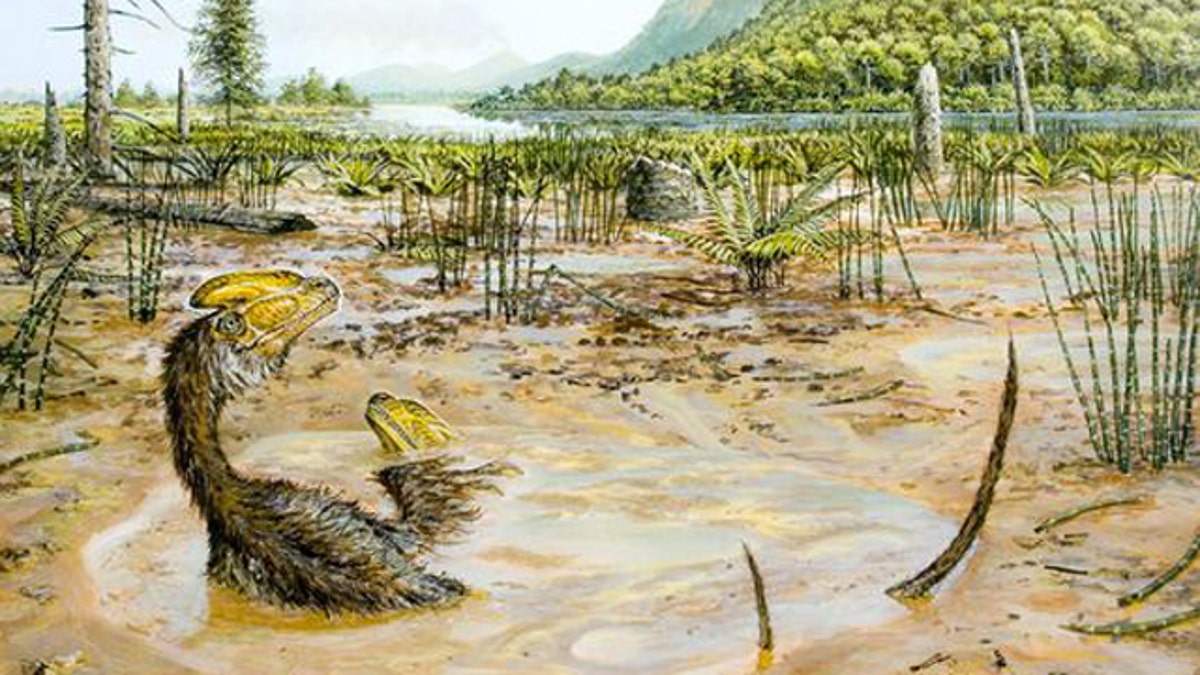

Two small Guanlong wucaii dinosaurs struggle to escape a muddy pit in what is now China during the late Jurassic period. (Michael Skrepnik)

Following in a giant dinosaur's footsteps could be fatal — but not for the reasons you might suspect.

Mysterious "death pits" holding the fossil skeletons of nearly two dozen small dinosaur species may actually be the 160-million-year-old footprints of an ancient behemoth, a new study suggests. The first of three dino-filled pits was unearthed nearly a decade ago in northwestern China's remote Xinjiang region.

SLIDESHOW: The Dinosaur Death Pits

Inside the 3.5- to 6.5-foot-deep depressions were the largely complete skeletons of several species of small theropods, bipedal raptors from the lineage that includes Tyrannosaurus rex.The stacked fossils included Guanlong, or "crested dragon," an aggressive, toothy predator with a Mohawk-like head adornment. Limusaurus, also found in the pits, was a probable herbivore with an intriguing hand that some experts believe links dinosaur limbs to bird wings.

Even as scientists celebrated these rare fossil finds, a mystery remained: What created the death traps in which the animals were entombed?

Treacherous Tracks

Analysis of the rocks surrounding the dinosaur fossils shows that the unfortunate animals were stacked up inside in a mixture of volcanic mudstone and sandstone, say geologist David Eberth and colleagues, whose work was partially funded by the National Geographic Society.

"All of the geological data indicated to us that we're dealing with sediments that were originally very rich in fluids," said Eberth, of Alberta's Royal Tyrrell Museum. "These were never empty holes in the landscape."

Instead, the death pits might have been created by the wanderings of the massive sauropod dinosaur Mamenchisaurus, Eberth's team suggests in the study, which will appear in the February issue of the journal PALAIOS.

Although the pits lie in what is now the Gobi desert, 160 million years ago the region was a marshy wetland. (Related pictures: life in the Jurassic period.)

But at some point during the late Jurassic, erupting volcanoes showered the area with massive amounts of ash. This volcanic debris created a semisolid surface over pockets of quicksand-like volcanic mud.

When Mamenchisaurus went for a walk across the strange landscape, the massive plant-eater's feet punched through the ashy surface, and the dinosaur's footprints became backfilled with thick mud, the study authors think.

Like beach walkers leaving their "vanishing" prints in wet sand, the huge dinosaur's filled-in prints became "invisible" pit traps.

At around 40 to 50 pounds each, comparatively tiny theropods and other small animals could have walked unhindered across most of the region's solid ash crust. But the dinosaurs would have easily gotten trapped if they had stumbled into Mamenchisaurus's muddy footprints.

Theropods in particular would have had a tough time escaping, since the dinosaurs used only their hind legs for locomotion, Eberth said. (Quiz: Test your dinosaur IQ.)

"It's very likely that other kinds of animals would have entered these pits but were able to get out," Eberth said. "We picture quadrupeds being able to get out of these pits because they essentially had a natural four-wheel-drive to pull themselves out."

In addition, small theropods were most likely coated in feathers that, when covered with mud, would have weighed them down further.

When an animal died, it would become at least partially submerged. Other creatures would then fall into the muddy trap, creating layers of entombed bodies.

After a few months, it's possible some animals were able to escape death because they could stand on the piled-up corpses, the study authors write.

Springing the Trap

The footprint idea is plausible, said Hans-Dieter Sues, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History.

"The small, possibly plant-eating theropod Limusaurus was common and conceivably could have traveled in small flocks or herds," said Sues, who was not involved with the study. "Many of these animals could become trapped on such treacherous ground."

"The larger predatory Guanlong would then have been attracted by seemingly easy prey and became itself ensnared in mud," he said.

Whatever the pits' origins, the importance of the skeletons found inside them is beyond doubt, he added.

Theropods of this era are considered closely related to birds and so are important pieces in reconstructing the evolution of flight. (Related: "New Feathered Dinosaur Found; Adds to Bird-Dino Theory.")

But even though the small raptors were common during the Jurassic, their remains are quite rare, he said. That's probably because theropod carcasses were typically ripped apart by predators, and their smaller bones were far less likely to survive to the present day.

Multiple individuals of the same species found together in the pits allow paleontologists to better understand the way dinosaurs grew and aged, as well as their roles in the larger ecosystem. The finds also help fill an enormous fossil gap for the middle to late Jurassic (see a prehistoric time line).

"Previously," Sues said, "we had known very little about dinosaurs and other land vertebrates from this particular time interval anywhere."