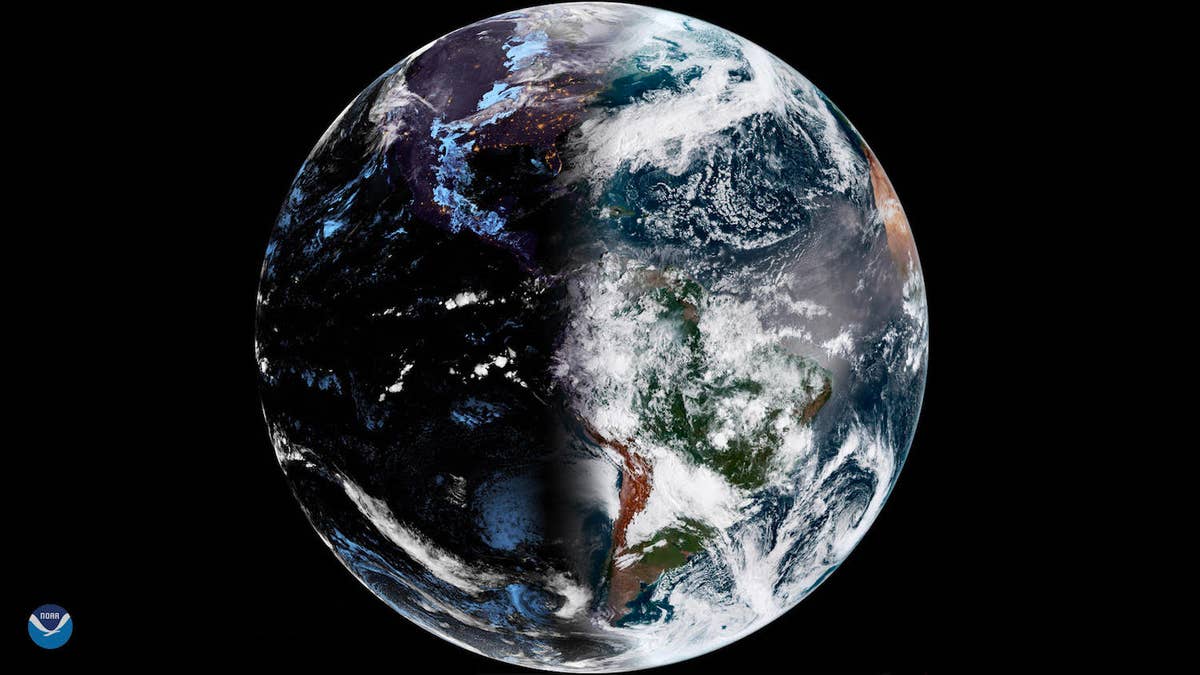

The forces of light and dark are basically equal at this moment on Earth. (NOAA; NOAA Environmental Visualization Laboratory)

Earth just got another dazzling glamour shot, thanks to a satellite that snapped its photo on the March 20 spring equinox. This photo shows half of the planet illuminated in light, and the other steeped in darkness, just like a black-and-white cookie.

This beautiful symmetry is no surprise for anyone who knows anything about the equinox. In Latin, equinox means "equal night." Twice a year, in March and September, the equinox happens when the amount of daylight and darkness are nearly equal at all latitudes, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Why aren't equinoxes more common? The answer has to do with Earth's tilt. Because the planet is tilted on its axis about 23.5 degrees, daylight is usually unequally distributed across the planet. Depending on where Earth is in its orbit around the sun, either the Northern Hemisphere or the Southern Hemisphere will have longer days or nights. [Earth Pictures: Iconic Images of Earth from Space]

"During two special times twice a year, the tilt is actually perpendicular to the sun, which means that Earth is equally illuminated in the Northern and Southern hemispheres," C. Alex Young, associate director for science in the Heliophysics Science Division at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, previously told Live Science.

More From LiveScience

In other words, the sun is directly above the equator at noon during an equinox.

This past week, the equinox happened at 5:58 p.m. EDT on Wednesday (March 20), marking the first astronomical day of spring for the Northern Hemisphere. The new image, however, was taken several hours before that, at 8 a.m. EDT, by the GOES EAST satellite.

Then GOES satellites, also known as the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite system, are a network of Earth-observing satellites operated by NOAA. They gather information on weather forecasting, severe storm tracking and meteorology research.

- 2013 Amazing Earth Images

- Photos: 2017 Great American Solar Eclipse

- See Gorgeous Pics of the #SuperBlueBloodMoon Eclipse

Originally published on Live Science.