NASA plans two missions to Venus

NASA aims for two new missions to Venus to learn more about the ‘lost habitable’ world; former NASA astronaut Tom Jones provides insight on ‘CAVUTO Live.’

NASA announced this week that citizen scientists had spotted a Jupiter-like exoplanet in data from its Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS).

In a Thursday news release, the agency wrote that Tom Jacobs, a former U.S. naval officer from Washington state, had helped to discover a giant gaseous planet about 379 light-years from Earth, orbiting a star with the same mass as the sun.

The finding, which was published in the Astronomical Journal, is significant because its 261-day year is long compared to many known gas giants outside our solar system.

RED SUPERGIANT STAR'S DEATH WITNESSED BY ASTRONOMERS FOR THE FIRST TIME: REPORT

The planet is also reportedly just a bit farther from its star than Venus is from the sun.

It is nearly three times more massive than Jupiter, but it's also denser.

The planet may have as much as 105 Earth masses worth of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, according to computer models.

Additionally, with an average temperature with about 170 degrees Fahrenheit, TOI-2180 b is warmer than room temperature on Earth – though strangely cold compared with other transiting giant exoplanets.

The study's lead author Paul Dalba, an astronomer at UC Riverside, said that tracking the planet required "a global uniting effort."

"Discovering and publishing TOI-2180 b was a great group effort demonstrating that professional astronomers and seasoned citizen scientists can successfully work together," Jacobs said in a statement. "It is synergy at its best."

Using TESS data, scientists look for changes in the brightness of nearby stars to help locate new planets.

Jacobs and the citizen "Visual Survey Group" examined plots of TESS data and used a program called LcTools, allowing them to inspect telescope data by eye.

On Feb. 1, 2020, Jacobs noticed a plot showing starlight from TOI-2180 dim by less than half a percent and then return to its previous brightness level over a 24-hour period.

JAMES WEBB SPACE TELESCOPE IS FULLY DEPLOYED

NASA explained that occurrence may indicate the presence of an orbiting planet that is said to "transit" as it passes in front of the star.

By measuring the light that dims, scientists can estimate how large the planet is and also its density.

The Visual Survey Group alerted Dalba and University of New Mexico assistant professor Diana Dragomir to the light curve: a graph showing starlight over time.

"With this new discovery, we are also pushing the limits of the kinds of planets we can extract from TESS observations," Dragomir said. "TESS was not specifically designed to find such long-orbit exoplanets, but our team, with the help of citizen scientists, are digging out these rare gems nonetheless."

In order to find planets, professional astronomers use computer algorithms to identify multiple transit events from a single star.

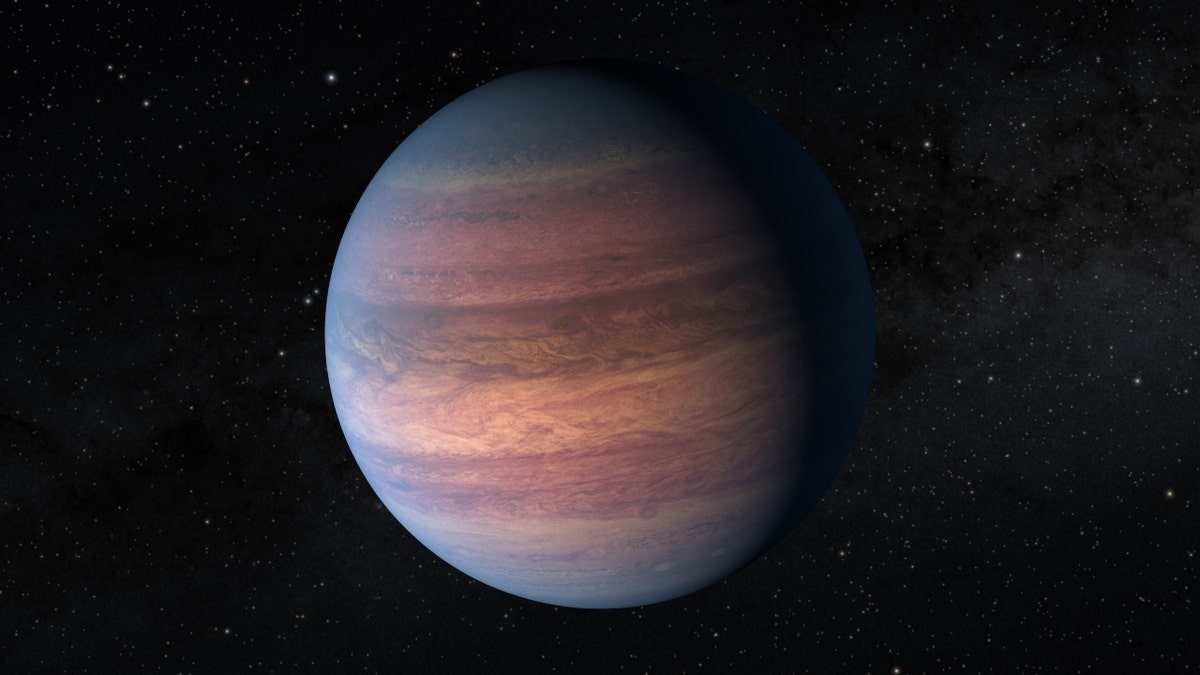

This illustration depicts a Jupiter-like exoplanet called TOI-2180 b. It was discovered in data from NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite. (Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt)

Manually, the Visual Survey Group found a "single transit event," but more observations were necessary to ensure the group had found a planet.

Dalba was able to use California's Lick Observatory Automated Planet Finder Telescope to measure the wobble of the star as well as Hawaii's Keck I telescope at the W. M. Keck Observatory.

While Dalba had continued to hunt down a second transit event, none of the telescopes at 14 sites across three continents in August 2020 detected the planet with confidence – and that was following 500 days of observations that allowed him and his colleagues to calculate the planet's mass and a range of orbit possibilities.

"Still, the lack of a clear detection in this time period put a boundary on how long the orbit could be, indicating a period of about 261 days. Using that estimate, they predict TESS will see the planet transit its star again in February 2022," NASA explained.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Next month, Dalba and the citizen scientists will look for the planet's signature.

The James Webb Space Telescope could potentially observe this planet and its atmosphere in the future, as well as look for the presence of small objects orbiting TOI-2180 b.

Although approximately 4,800 exoplanets have been confirmed, there are thought to be billions in our galaxy.