Fox News Flash top headlines for Jan. 23

Fox News Flash top headlines for Jan. 23 are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com

A mummified Egyptian priest has come to life -- sort of -- some 3,000 years after his death through the mimicking of his voice.

Nesyamun, who lived during the rule of pharaoh Ramses XI between 1099 and 1069 B.C., recently spoke with the help of modern technology: 3D printed versions of his mouth and throat, according to a paper published by Scientific Reports.

The research conducted by academics from the University of London, the University of York and the Leeds Museums and Galleries were published Thursday.

WILL TITANIC'S SUNKEN WRECK BE PROTECTED? TREASURE HUNTERS ARE SKEPTICAL OF NEW US, UK AGREEMENT

The mummified body of Nesyamun laid on the couch to be CT scanned at Leeds General Infirmary. (Leeds Teaching Hospitals/Leeds Museums and Galleries) (Leeds Teaching Hospitals/Leeds Museums and Gallerie)

The research "has given us the unique opportunity to hear the sound of someone long dead," said study co-author Joann Fletcher, a professor of archaeology at the University of York, according to the BBC.

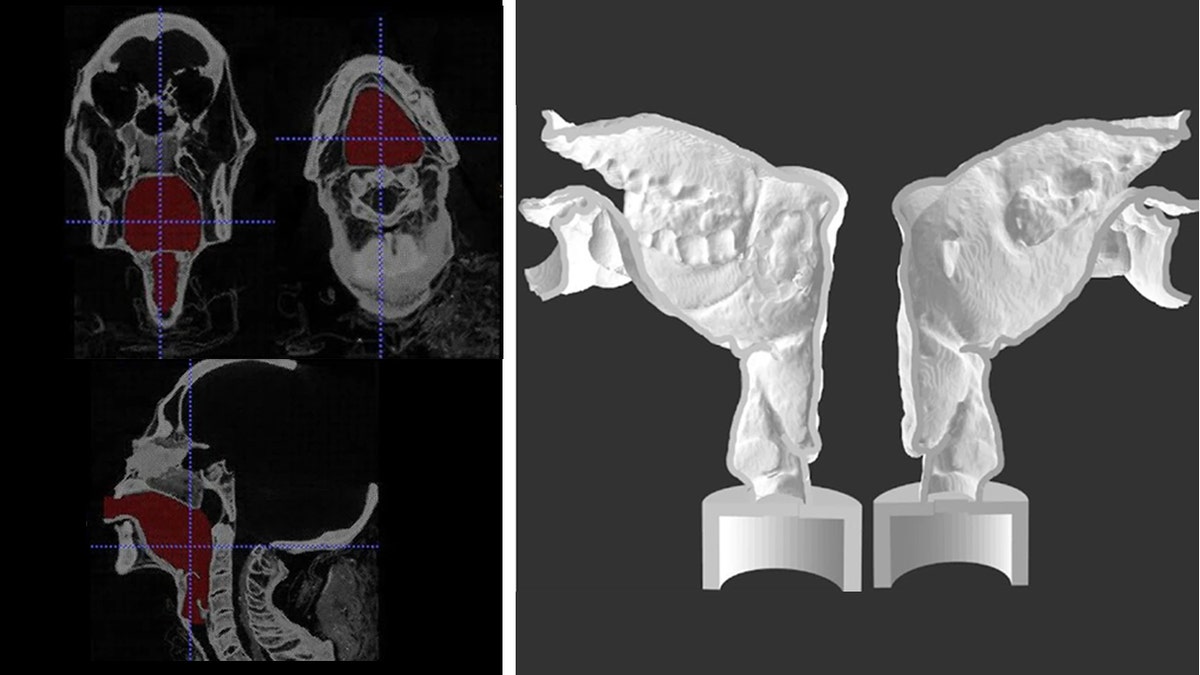

To copy the sound produced by Nesyamun's voice tract, his body was put through a CT scanner and a 3D version was printed to make sure the tract was preserved. An artificial larynx sound was then generated.

The voice reproduced resembled the "ah" and "eh" sounds.

“We have made a faithful sound for his tract in its current position, but we would not expect an exact speech match given his tongue state,” co-author David M. Howard of London's Royal Holloway college said.

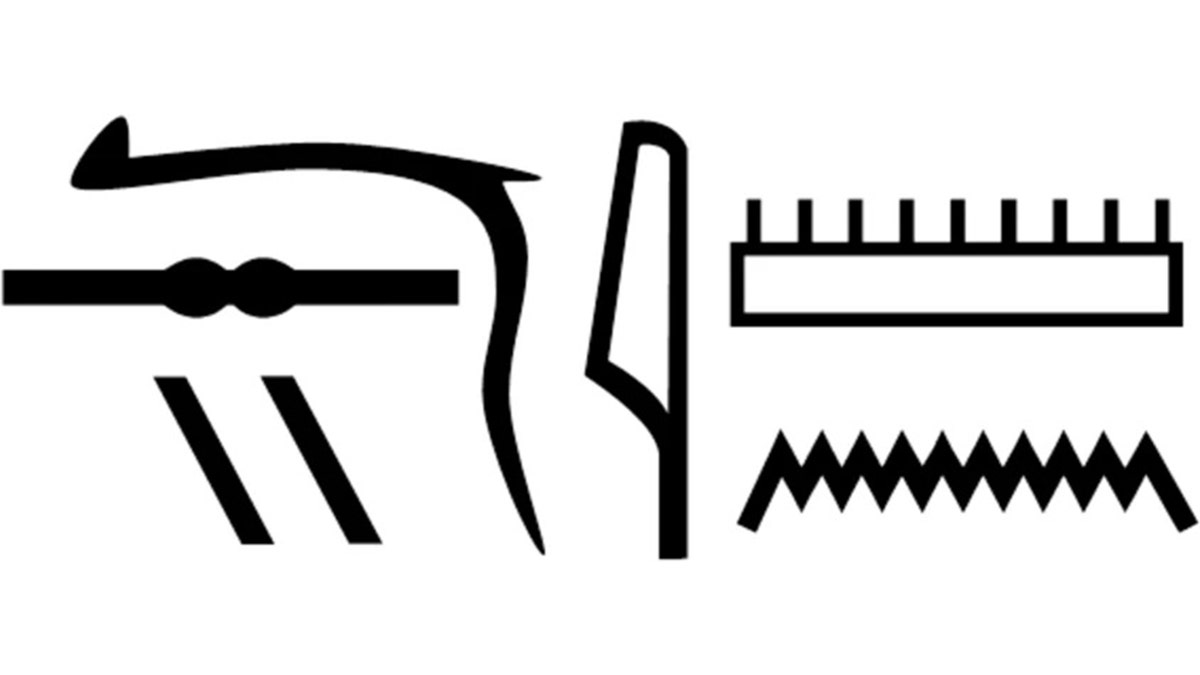

Nesyamun expressed his wish to be heard in the afterlife. His coffin had the inscription: "Nesyamun, true of voice."

ANCIENT SCULPTURE LOOTED FROM AFGHANISTAN RETURNED AFTER BEING FOUND ON AUCTIONEER'S WEBSITE

Final segmentation view (left) and sagittal section of the two halves of 3-D printed Nesyamun’s vocal tract (rigth). The lack of tongue muscular bulk and soft palate is (Scientific Reports) (Scientific Reports)

"In a way, we've managed to make that wish come true," Fletcher said.

Rudolf Hagen, an ear, nose and throat expert at the University Hospital in Wuerzburg, Germany, who specializes in thorax reconstruction and wasn't involved in the study, expressed skepticism. Even cutting-edge medicine struggles to give living people without a thorax a “normal” voice, he said.

Co-author John Schofield, an archaeologist at the University of York, said the technique could be used to help people interpret historical heritage.

“When visitors encounter the past, it is usually a visual encounter,” said Schofield. “With this voice we can change that, and make the encounter more multidimensional.”

Nesyamun’s name in hieroglyphs as shown in his coffin inscriptions. (Scientific Reports) (Scientific Reports)

The technique could be used to interpret historical heritage, said co-author John Schofield, an archaeologist at the University of York.

“When visitors encounter the past, it is usually a visual encounter,” said Schofield. “With this voice we can change that, and make the encounter more multidimensional.”

The Associated Press contributed to this report.