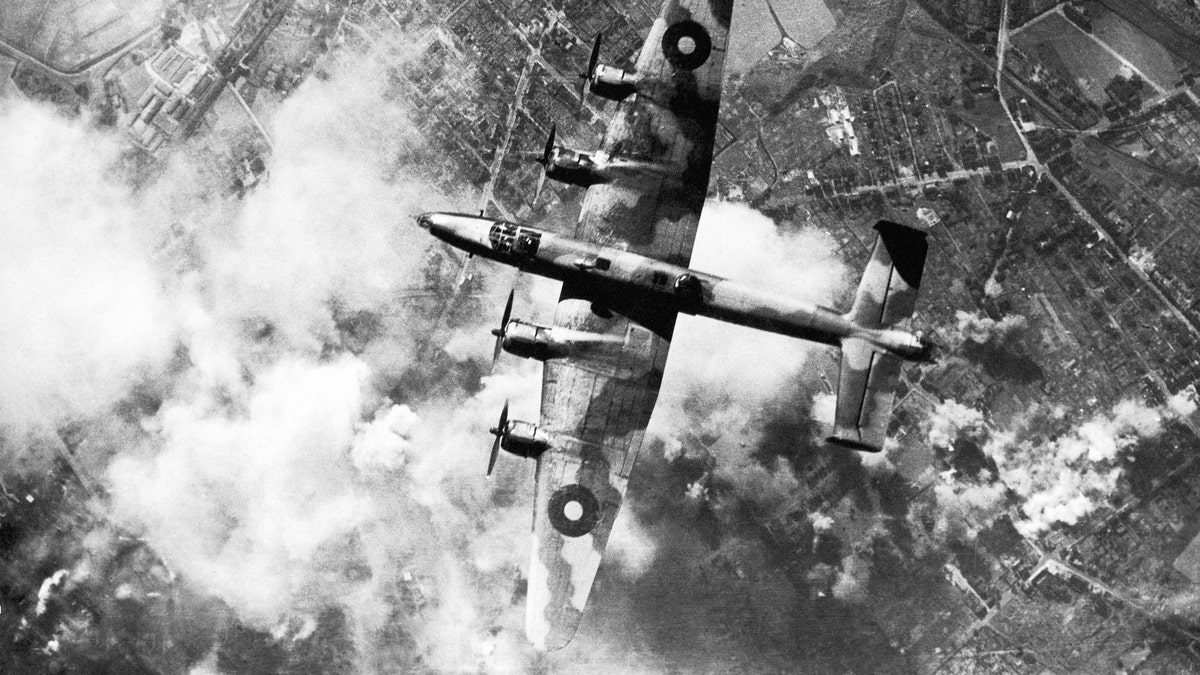

File photo - A Halifax bomber of RAF Bomber command flies over a synthetic oil plant in Germany's Ruhr region during a daylight attack on Oct. 20 1944. The plant itself is obscured by smoke from many bomb blasts. (Photo by Daily Mirror/Mirrorpix/Mirrorpix via Getty Images)

Massive bombing raids by Allied forces during World War II sent shockwaves to the edge of space, according to stunning new research.

Scientists at the University of Reading in the U.K. have revealed that shockwaves from huge bombs dropped on European cities travelled through the Earth’s atmosphere. The bombing even weakened the Earth’s electrified upper atmosphere, the ionosphere, 621 miles away.

The research could provide a valuable insight into how the likes of lightning, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions affect the Earth’s upper atmosphere.

STERN OF US WW II DESTROYER DISCOVERED NEAR REMOTE ALASKAN ISLAND: SURVIVOR RECOUNTS HARROWING DAY

“It is astonishing to see how the ripples caused by man-made explosions can affect the edge of space. Each raid released the energy of at least 300 lightning strikes,” said Chris Scott, professor of space and atmospheric physics, at the University of Reading, in a statement. “The sheer power involved has allowed us to quantify how events on the Earth’s surface can also affect the ionosphere.”

File photo - An RAF Lancaster bomber over the German city of Hamburg during a bombing raid. (Photo by SSPL/Getty Images)

The study, which is published in Annales Geophysicae, examined daily records complied at the Radio Research Centre in Slough, U.K., that were collected between 1943 and 1945. The Centre sent sequences of radio pulses over a range of shortwave frequencies 62 miles to 186 miles above the Earth’s surface. The pulses revealed the height and electron concentration of ionization within the Earth’s upper atmosphere.

Scientists studied the ionosphere response records from the time of 152 large Allied air raids on Europe.

WRECK OF WW II SHIP DISCOVERED 74 YEARS AFTER IT DISAPPEARED DURING A RESCUE MISSION

Influenced by solar activity, the ionosphere impacts radio communications, GPS, radio telescopes and some early warning radar, but the extent of its impact on World War II radio communications was unclear, researchers note. However, by studying wartime records scientists found that the electron concentration in the upper atmosphere decreased significantly as a result of the shockwaves from bombs detonating. “This is thought to have heated the upper atmosphere, enhancing the loss of ionization,” they say, in the statement.

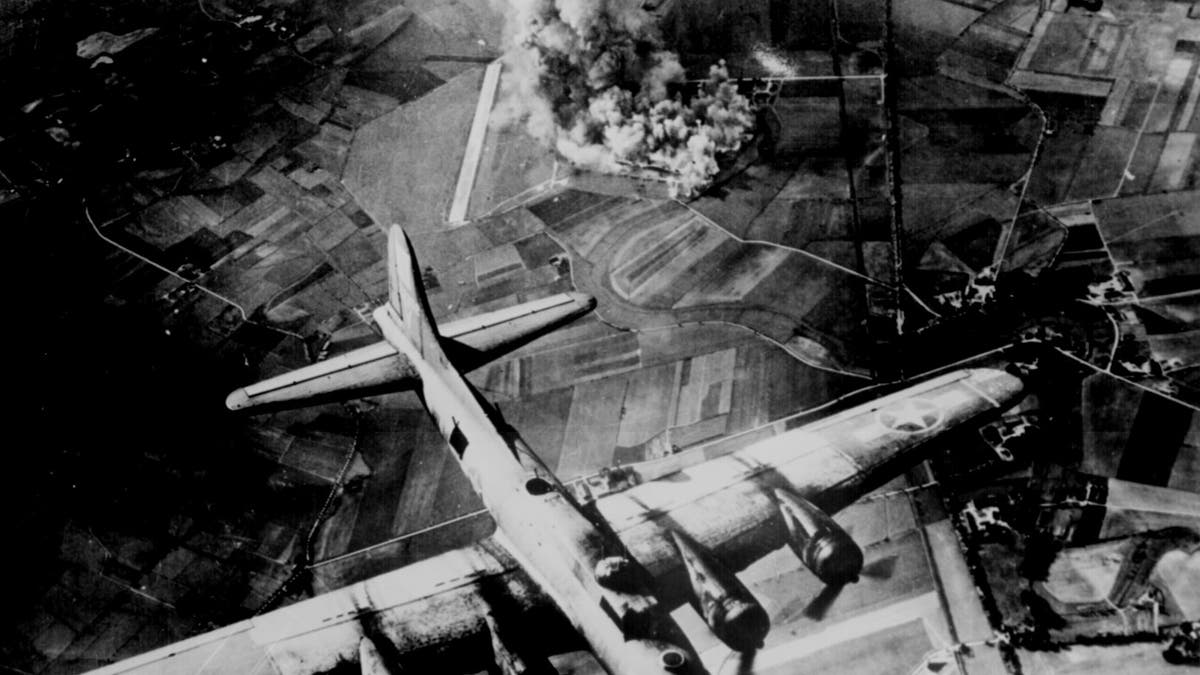

File photo - A raid by the 8th Air Force on the Focke Wulf factory at Marienburg, Germany (1943). (National Archives and Records Administration)

Allied forces inflicted heavy damage during their bombing raids on Germany, dropping ordnance such as the massive ‘Grand Slam’ bomb, which weighed up to 10 tonnes. Deployed by the Royal Air Force, ‘Grand Slam’ was the brainchild of Barnes Wallis, designer of the famous ‘Dambusters’ ‘bouncing bomb’.

“Aircrew involved in the raids reported having their aircraft damaged by the bomb shockwaves, despite being above the recommended height,” said Professor Patrick Major, University of Reading historian and a co-author of the study, in the statement. “Residents under the bombs would routinely recall being thrown through the air by the pressure waves of air mines exploding, and window casements and doors would be blown off their hinges. There were even rumors that wrapping wet towels around the face might save those in shelters from having their lungs collapsed by blast waves, which would leave victims otherwise externally untouched.”

Set against this backdrop, the study of ionosphere response records offers fresh insight into the effects of the bombing campaign, according to Major. “The unprecedented power of these attacks has proved useful for scientists to gauge the impact such events can have hundreds of kilometres above the Earth, in addition to the devastation they caused on the ground,” he said in the statement.

File photo - RAF plane dropping bombs over Duisburg, Germany, Oct. 15 1944. (Photo by SSPL/Getty Images)

The shockwaves from major other major wartime explosions have been felt large distances away. During World War I, for example, British forces exploded 19 huge mines under German trenches in Belgium. The resulting explosion was the largest blast of the pre-atomic bomb era, according to National Geographic and was reportedly heard by British Prime Minister David Lloyd George in London, 140 miles away. At the geology department of Lille University in France the shockwave registered as an earthquake.

The ionosphere also featured in a recent research study that cited a devastating volcanic eruption on the other side of the world as contributing to Napoleon’s defeat in the Battle of Waterloo.

NAPOLEON DYNAMITE: HOW AN INDONESIAN VOLCANO INFLUENCED THE BATTLE OF WATERLOO

For years, historians have cited rainy and muddy conditions on the day of the battle as a factor in the French Army’s famous defeat on June 18, 1815. Waterlogged conditions at the battle site prompted Napoleon to delay his troops’ attack until the ground dried out, widely regarded as a critical error.

In a research study published in the journal Geology, scientists from Imperial College London linked the weather conditions to the eruption of the Mount Tambora volcano 7,680 miles away. The volcano on the Indonesian island of Sumbawa sent electrically-charged volcanic ash into Earth’s atmosphere when it erupted in April 1815 and “short-circuited the ionosphere.” This led to a pulse in cloud formation, which in turn brought heavy rain across Europe, according to the study.

Follow James Rogers on Twitter @jamesjrogers