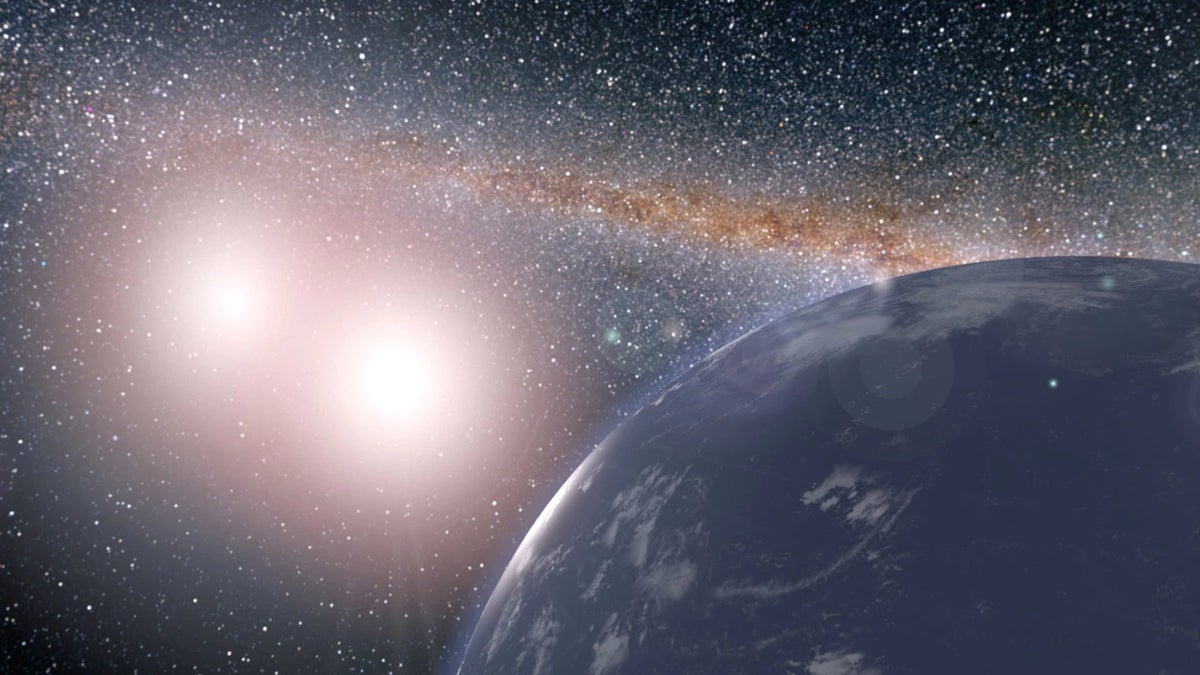

An artist's concept of a planet covered in water. New research suggests such worlds could be more likely to support life than thought. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Even on alien worlds covered by water, a new study shows that there's a chance for life to survive for a long time — despite previous research showing that's unlikely.

Past research has said that these so-called "water worlds" could be unfriendly to life because they would not allow for mineral and gas cycling that stabilizes the climate on Earth. A new study, however, counters that ocean planets could sustain habitability for quite a long time after formation, although how long depends on the individual planet.

Scientists have found thousands of exoplanets in the past two decades, with a good percentage of them being rocky and in the "habitable zone" of their parent stars — where water could exist on the planet's surface. However, scientists still aren't sure about all the conditions for habitability, because so far we know of only a single world with life: Earth. [10 Exoplanets That Just Might Support Life]

On Earth, scientists often look to our own climate to better understand how planets in general could keep their conditions steady for millions or billions of years, long enough for life to get a toehold, according to a statement on the new work. Our planet warms up by releasing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, through volcanoes, and then cools down by dissolving those gases into minerals in the crust.

More From Space.com

The new research, based on more than 1,000 simulations of exoplanets under formation, suggests that water worlds could be habitable if they meet certain conditions, researchers said in the statement. Specifically, these planets would need to have a certain amount of carbon — the element on which Earth's life is based. The exoplanet would need a lot of water early in its formation, and the ability to cycle carbon between the atmosphere and the ocean to stabilize the system.

Also, the exoplanet crust would need to maintain its original elements and minerals, instead of having those minerals and elements dissolve in the ocean and pull out the carbon in the atmosphere.

"This really pushes back against the idea you need an Earth clone — that is, a planet with some land and a shallow ocean," lead author Edwin Kite, a geophysicist at the University of Chicago, said in the statement.

While they ran simulations for planets around stars that are similar to the sun, Kite said the research also leads to optimism for red dwarf stars — another hotspot to search for life. That's because the simulation only assumed steady light from a star, which, in theory, a red dwarf would also provide.

Red dwarfs are dimmer than our own sun, but if planets are close enough to the star, they could, theoretically, have water on their surfaces and meet the conditions for habitability. However, these stars are also extremely variable and could send out life-killing radiation to their planets.

The new research was detailed Aug. 31 in The Astrophysical Journal.

Original article on Space.com.