Fox News Flash top headlines for March 5

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

Some of the earliest animals on Earth stayed connected via networks of thread-like filaments that helped them to dominate the planet's oceans about half a billion years ago.

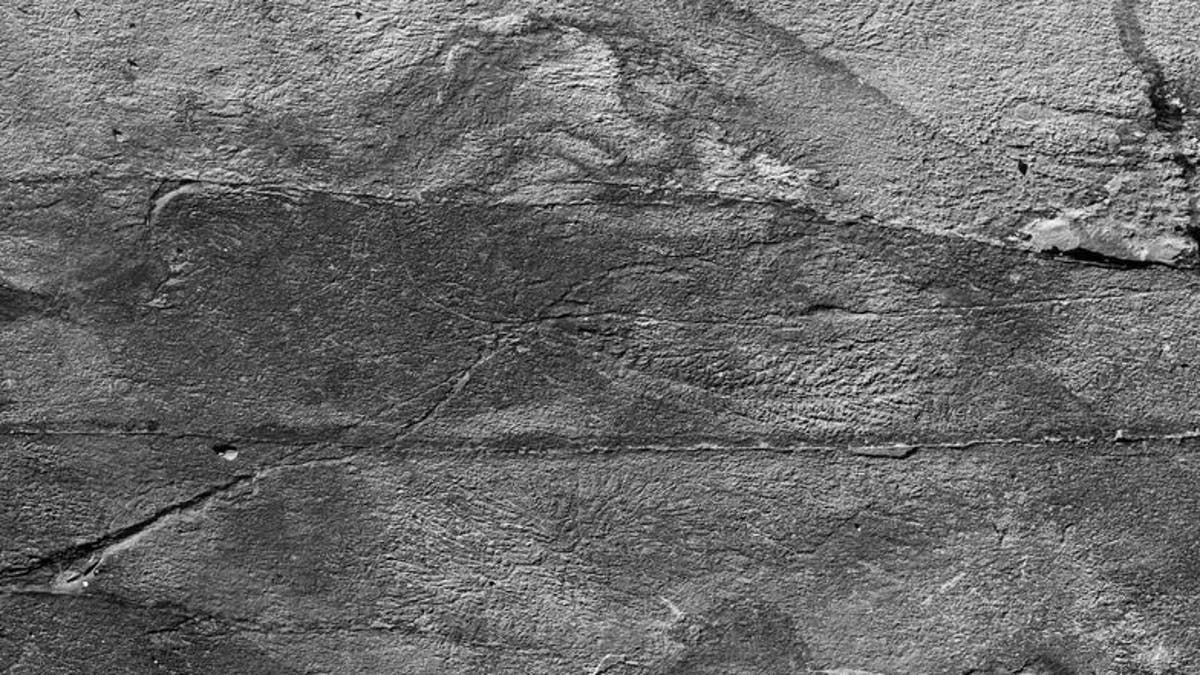

Scientists from the Universities of Cambridge and Oxford found the fossilized threads, which in some cases were as long as 12 feet, connecting strange organisms known as rangeomorphs.

These filament networks, which may have been used for food, communications or reproduction, were discovered in seven species across dozens of fossil sites in Canada, according to researchers.

The fern-like rangeomorphs were very successful during the Ediacaran period, about 571 and 541 million years ago. They have long fascinated scientists, in part because they do not seem to have had mouths, organs or a means of getting around.

NASA'S CURIOSITY MARS ROVER SNAPS STUNNING PANORAMY OF THE RED PLANET

Fossilized threads, some as long as 12 feet, connecting organisms known as rangeomorphs, which dominated Earth's oceans half a billion years ago. (Alex Liu)

"These organisms seem to have been able to quickly colonise the sea floor, and we often see one dominant species on these fossil beds," Alex Liu, of Cambridge's Department of Earth Sciences and the paper's first author, said in a statement. "How this happens ecologically has been a longstanding question -- these filaments may explain how they were able to do that.

"We've always looked at these organisms as individuals, but we've now found that several individual members of the same species can be linked by these filaments, like a real-life social network," explained Liu.

Researchers say the filaments may have been used as a type of clonal reproduction, similar to strawberry plants, which can be asexually reproduced. It's also possible that the filaments allowed organisms to share nutrients.

"It's incredible the level of detail that can be preserved on these ancient sea floors; some of these filaments are only a tenth of a millimetre wide," said co-author Frankie Dunn, from the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, in a statement. "Just like if you went down the beach today, with these fossils, it's a case of the more you look, the more you see."