Fox News Flash top headlines for July 31

Fox News Flash top headlines for July 31 are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com

Even Harrison Ford would be proud.

The fossil of a newly discovered crab that lived more than 500 million years ago has been named after the Millennium Falcon, the starship that Ford's character, Han Solo, flew during "Star Wars."

Known as Cambroraster falcatus, the ancient creature had "rake-like claws and a pineapple-slice-shaped mouth at the front of an enormous head." It also reached up to a foot in length, according to a statement announcing the findings.

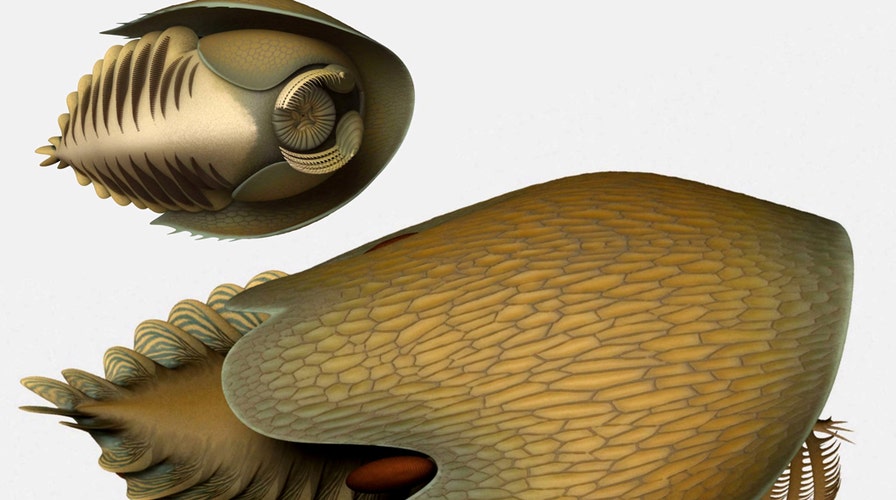

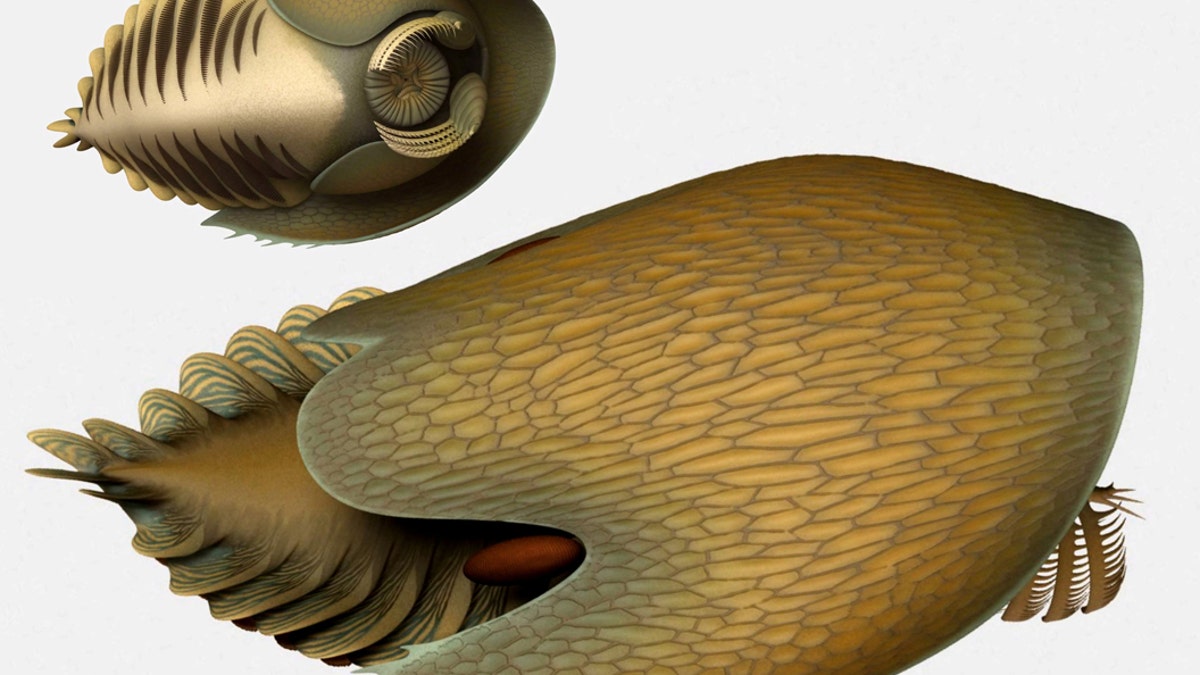

A reconstruction of the ancient organism Cambroraster falcatus, a giant crab that prowled the ocean beds more than 500 million years ago. (Credit: Lars Fields, Royal Ontario Museum)

'UTTERLY BIZARRE' CHIMERA CRAB FOSSIL DISCOVERED: MAKES YOU WONDER 'WHAT ELSE IS OUT THERE'

"Its size would have been even more impressive at the time it was alive, as most animals living during the Cambrian Period were smaller than your little finger," said Joe Moysiuk, the study's lead author, in the statement.

C. falcatus, which resembles a modern-day horseshoe crab, gets the second part of its name from the large shield-like carapace that covered its head, which is shaped like Solo's spacecraft.

"With its broad head carapace with deep notches accommodating the upward facing eyes, Cambroraster resembles modern living bottom-dwelling animals like horseshoe crabs," Moysiuk added. "This represents a remarkable case of evolutionary convergence in these radiodonts."

The Millennium Falcon in "Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope." (Fair Use, Screengrab/Lucas Film)

The fossils were discovered in the 506-million-year-old Burgess Shale, at several sites in the Marble Canyon area in Kootenay National Park, British Columbia.

In addition to its scary, predator features, C. falcatus had a varied diet. It preyed on a number of different insects, crabs and spiders, by using its claws, which look like "forward-directed rakes."

"We think Cambroraster may have used these claws to sift through sediment, trapping buried prey in the net-like array of hooked spines," the study's co-author, Jean-Bernard Caron, added in the statement.

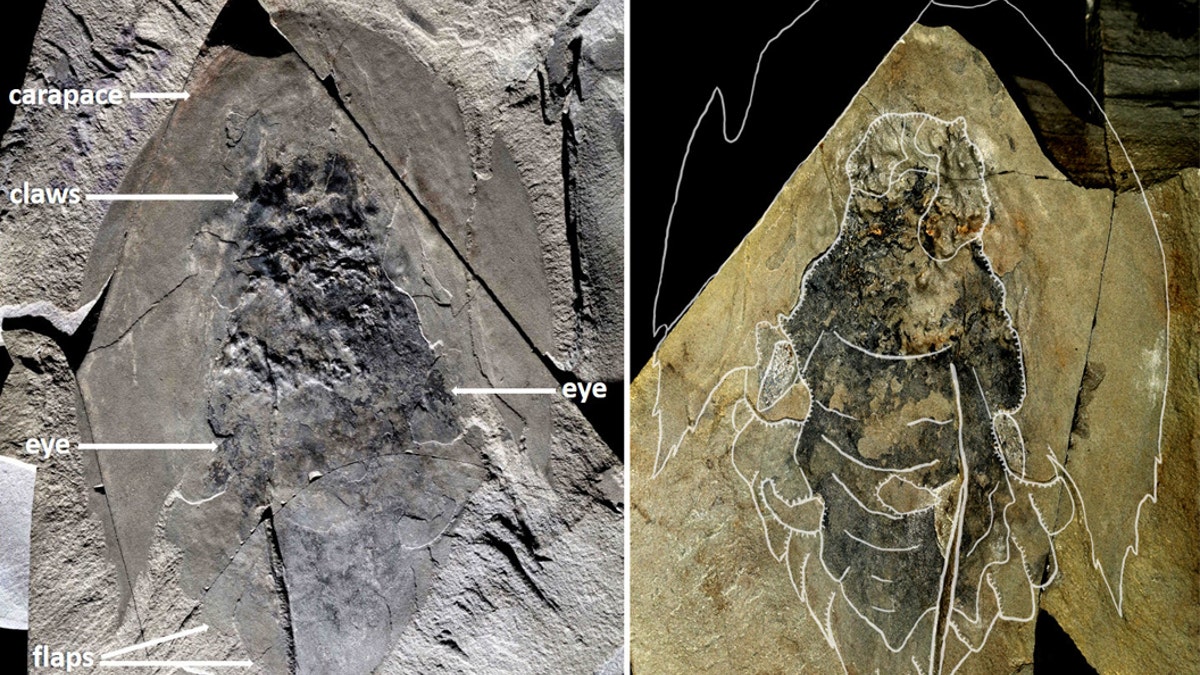

Complete fossil (Holotype ROMIP 65078) of Cambroraster falcatus, showing the eyes and the body with paired swimming flaps below the large head carapace. The shale in which the fossil was entombed was split open, leaving parts of the body on both sides (right and left). (Credit: Jean-Bernard Caron© Royal Ontario Museum)

Moysiuk added that he was impressed by its size, given most of the creatures that lived during the Cambrian Period "were smaller than your little finger."

Perhaps not surprisingly, Cambroraster was a distant relative of Anomalocaris, "the T Rex of the Cambrian," a prehistoric fish with sharp teeth. Despite its close relation to Anomalocaris, Moysiuk said that the crab seemed "to have been feeding in a radically different way."

FOSSILIZED REMAINS OF 430 MILLION-YEAR-OLD SEA MONSTER FOUND

Caron added that the number of fossils found in recent years is "extraordinary," as the researchers have found "hundreds of specimens," including dozens found in a single rock slab. This has allowed the researchers to create the creature with stunning and unprecedented detail.

"The radiodont fossil record is very sparse; typically, we only find scattered bits and pieces. The large number of parts and unusually complete fossils preserved at the same place are a real coup, as they help us to better understand what these animals looked like and how they lived," Caron continued. "We are really excited about this discovery. Cambroraster clearly illustrates that predation was a big deal at that time with many kinds of surprising morphological adaptations."

Given the prevalence of the fossils found at the various sites, researchers believe there could be additional new species waiting to be discovered.

The research has been published in the scientific journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.