(Movoto.com)

Here at Movoto Real Estate, we have a special affection for board games, as evidenced by our recent forays into the real estate of Monopoly and Clue. Milton Bradley’s “The Game of Life” was our next obvious venture into fictional real estate. This classic American board game offers all the fun of mortgage payments, dead-end jobs, and unplanned pregnancies. Milton himself created the game in 1860, originally calling it “The Checkered Game of Life.” The version we’re all familiar with, however, was created by toy designer Reuben Klamer and released in 1960.

Since then, at least seven revised versions have been released. The game’s content has evolved through the years, reflecting changing social values, inflation, and new standards of political correctness. The game board, though, has remained relatively unchanged since Klamer’s version. Similar to real life, one’s fate can come down to factors as seemingly random as a spin of a plastic number wheel.

Before we get to the houses, let’s take a look at how “The Game of Life” found its way into the American living room.

Old School Board Games

The Mansion of Happiness: An Instructive Moral and Entertaining Amusement

Designed by S.B. Ives and released in 1843, “The Mansion of Happiness” is like “The Game of Life”’s judgmental grandpa. With its subtitle full of redundancies and heavy-handed Christian message, this game probably wouldn’t catch on today. The game’s spiral board is divided into “virtue” and “vice” spaces, with “virtue” propelling players forward and “vice” setting them back.

The site BoardGameGeek quotes the game’s rules:

“WHOEVER possesses PIETY, HONESTY, TEMPERANCE, GRATITUDE, PRUDENCE, TRUTH, CHASTITY, SINCERITY…is entitled to Advance six numbers toward the Mansion of Happiness. WHOEVER gets into a PASSION must be taken to the water and have a ducking to cool him… WHOEVER posses[ses] AUDACITY, CRUELTY, IMMODESTY, or INGRATITUDE, must return to his former situation till his turn comes to spin again, and not even think of HAPPINESS, much less partake of it.”

Sounds like the perfect game for your next cocktail party!

The Checkered Game of Life

With its intriguing “Disgrace,” “Suicide,” and “Fat Office” squares, Milton Bradley’s prototype for the modern “Game of Life” aimed to teach its players valuable lessons for leading a moral lifestyle. The game used a six-sided top, called a teetotum, because dice were too closely associated with Satan and gambling.

The Game of Life

The modern “Game of Life” has inspired countless spinoff versions, including SpongeBob, Family Guy, The Simpsons, and The Wizard of Oz. There are now computer versions of the game, and an iPhone app.

If you’ve never played, here’s how the game goes. Each player is represented by a small plastic car. In the 1960 version, this car resembled a convertible; it was changed in the late ‘80s version to something closer to a minivan. The cars each have six holes into which the “person pegs” can be wedged.

As in real life, each player begins the “Game of Life” as a lone person peg, colored pink or blue, depending on gender preference. When you land on a “have a baby” space, you must add a pink or blue peg to the car. “If you get more than four children, just crowd them in as you do in real life!” the 1971 game manual cheerfully counsels.

Unlike real life, however, “The Game of Life” can be reassuringly simple. To choose a career, you select three of the nine career cards at random and choose one of those three. For housing, you pick one of the nine cards at random, and are stuck with it. (Luckily, the most expensive house is only $200,000.)

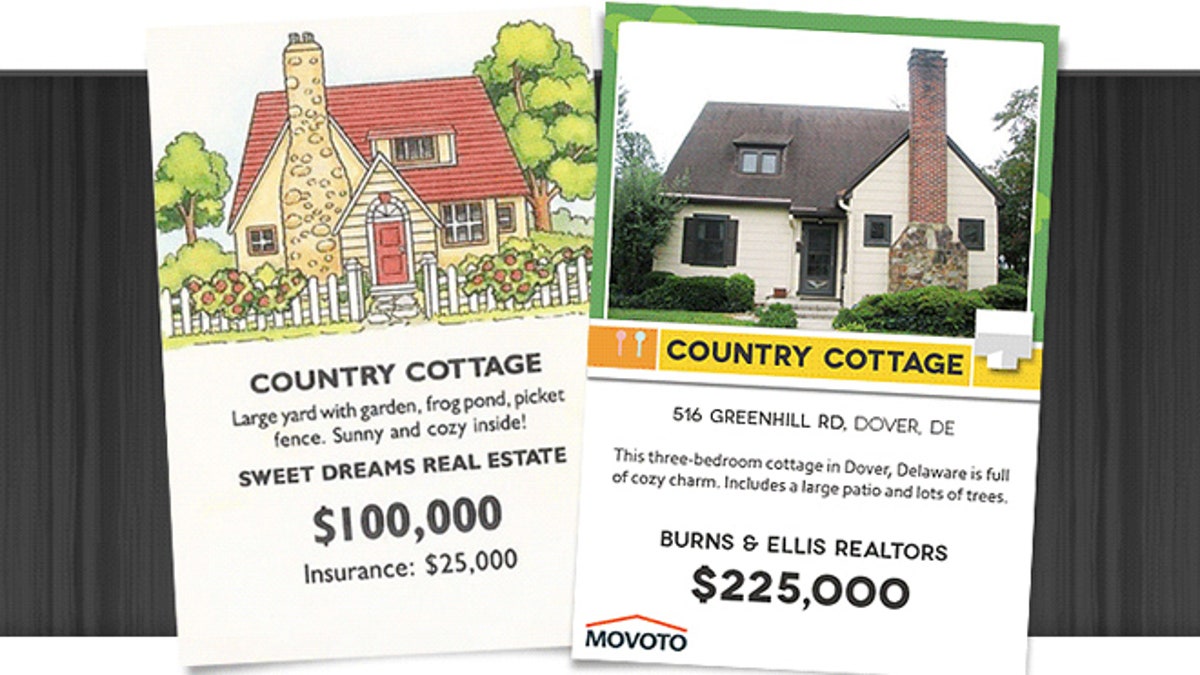

The housing cards came along in the 1991 edition of the game, and we figured it was time for an update. We’ve found comparable houses currently on the market, so you can get a sense of what your favorite “Life” house is really worth. Some of the answers might surprise you.

Click to view a photo gallery of the real value of the Game of Life houses.

Related:

- Real World Monopoly: Marvin Gardens is the New Boardwalk

- The Real Life Clue Mansion: This Price Will Kill You

Kate Folk is a writer for Movoto.