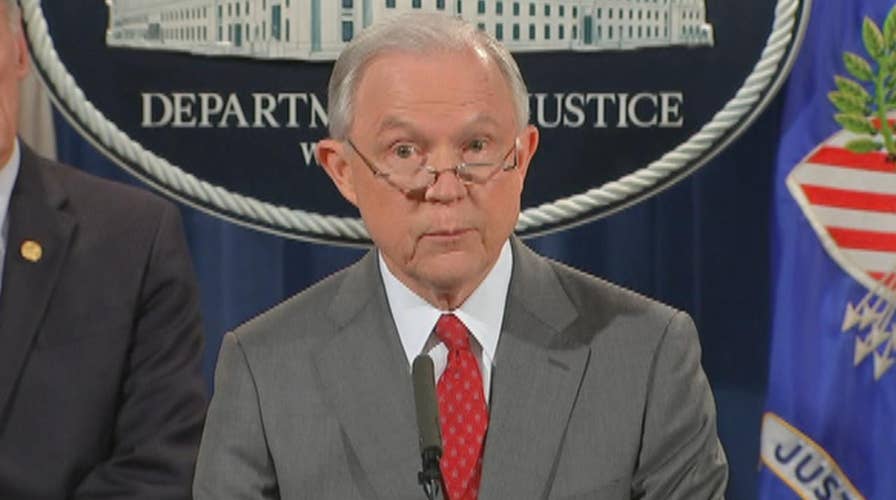

Sessions announces steps to crack down on leakers

Attorney general says leaks of classified material threaten national security

When the National Basketball Association wanted to stop a torrent of internal memos from being leaked to the media, it turned to classic spycraft.

League officials conducted a sting operation in 2010, in which they changed a few numbers or words in the copies of the memos that were going out to different teams.

When one of those memos was leaked to the press and reported, the NBA immediately spotted the difference and got their man.

In this case, it was Detroit Pistons official Joe Dumars, who was fined $500,000 for leaking information to an online sports reporter.

“That source may or may not be a leaker. The point is that this approach narrows the scope of potential suspects.”

The technique the NBA used is called a “barium meal test” after the drink taken to make the gastrointestinal system visible during a CAT scan.

That test is one of several options in the government’s toolkit for hunting down the leakers in the West Wing, the intelligence community, or wherever they might be.

As far as the Trump leakers are concerned, only one has been publicly apprehended and charged, mostly due to sloppy techniques on the part of the alleged leaker. But according to experts, technology also played a key role.

Reality Winner, the former National Security Agency contractor who leaked a classified document on Russian interference in the 2016 election, was caught when the document was posted online.

The hi-res color image showed a crease, suggesting it had been printed and hand-carried out of a secure space. The document she printed out was also branded with a digital watermark.

In the case of the intelligence community, a watermark is a unique string of digital code often inserted into each copy of a document, so that if and when it’s shared without authorization, it’s possible to identify its original source.

General James E. Cartwright, USMC Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, testifies before the Senate Armed Services Committee hearing on a repeal of section 654 of title 10, United States Code, "Policy Concerning Homosexuality in the Armed Forces" on Capitol Hill in Washington December 3, 2010. Sen. John McCain (R-AZ) warned on Thursday it might be too soon to end the U.S. military's ban on gays, as the party geared up to block President Barack Obama's bid to repeal the "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" policy this year. REUTERS/Hyungwon Kang (UNITED STATES - Tags: MILITARY POLITICS HEADSHOT) - RTXVCZY (REUTERS)

“That source may or may not be a leaker,” said Steven Aftergood of the Project on Government Secrecy at the Federation of American Scientists, “the point is that this approach narrows the scope of potential suspects.”

In Winner’s case, the digital watermark on her document was tied to a specific printer – a Xerox Docucolor with model number 54, serial number 29535218.

She was one of a handful of workers with access to that printer, and after a NSA audit found she was the only one who communicated with the website, she was taken into custody.

“That was easy,” said cybersecurity adviser Morgan Wright, mostly because Winner apparently failed to cover her digital tracks.

Wright said there are a variety of other technological options available to investigators.

They include: electronic intercept of all types of communications, software that can be secretly loaded into a device like a mobile phone to watch activity in real time, behavioral analytics that look for unusual activity such as downloading files onto a USB removable drive, and automated access logs that may help determine who accessed classified information within a particular time period.

“The problem with some of the software was the number of false positives - red herrings,” said Wright. “While it's gotten better, there is no holy grail tech that is foolproof...yet.”

“Technological approaches can sometimes improve the odds, but can't guarantee that an investigative conclusion will be reached,” agreed Aftergood.

Thus, the Trump Administration is said to be “shopping” for new technologies to plug the leaks.

It all gets more complicated when the leakers know the tricks and how to cover their tracks.

The case of former four-star Gen. James Cartwright, who was called President Obama’s “favorite general” until his fall from grace, illustrates the steps investigators often have to go through to close a complicated leak investigation.

According to Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, who in 2012 oversaw the Cartwright investigation, the evidence showed that the general disclosed classified information without authorization to two reporters.

In getting Cartwright to plead guilty to lying to the FBI about it all, “tens of thousands” of documents were collected through subpoenas, search warrants, and records requests, and scores of government employees were interviewed.

Once investigators narrowed down the list of possible suspects to Cartwright, it was probably just a matter of obtaining a warrant to go through personal emails, said Wright, since it was unlikely he would have used his official email to send the information to the reporters.

“Cartwright appears to have been caught through an FBI interview that was provably false through emails to a reporter that were obtained in the investigation,” Wright told Fox News, “Nothing too fancy - just good leg work.”

A big problem facing President Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions is that much of what is leaked does not rise to the level of criminality, making it harder if not legally impossible to obtain a warrant to do the necessary scouring of personal emails or other evidence protected by the law.

That might explain why Winner is the only one publicly charged with a crime thus far, though Attorney General Jeff Sessions said that four people have been charged with unauthorized disclosures.

“I think the most important reason is that most leaks are not crimes,” said Aftergood.

A leak potentially becomes a crime under the Espionage Act statutes whenever national defense or almost all other classified information is disclosed to an unauthorized person, as in Cartwright’s case.

“But unauthorized disclosure of private conversations or White House intrigue would not qualify as a crime in most cases,” Aftergood told Fox News. “It could be a firing offense, but not a basis for prosecution.”

As for the recipients of the leaks, they, too, can become the subject of the investigation, according to Wright, “to try to identify his or her typical sources and known contacts. Phone or email or other records may be scrutinized.”

The Obama administration began a crackdown on leakers under the Espionage Act that the Trump administration appears to be building off, and that has journalists up in arms.

“The Espionage Act is a 100-year-old law originally used to go after spies,” said Alexandra Ellerbeck of the Committee to Protect Journalists, “but its use over the past eight years against journalists' sources has the potential to chill the flow of information and reporting about serious concerns in the public interest.”

Sessions has said he is reviewing standards put in place to protect reporters amid a firestorm of criticism by the media against the Obama administration for its treatment of journalists.

“While imperfect, these standards were a welcome response to criticism of the Obama administration from journalists and transparency advocates. Subpoenas directly to reporters or to third party technology companies hit at the fundamental need of reporters to protect their sources, which is crucial to their ability to keep the public informed,” said Ellerbeck.