Fox News Flash top headlines for February 8

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

"We have to do a new AUMF," said House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif.

To the uninitiated, an AUMF is Washington shorthand for an "authorization for use of military force." A strict reading of the Constitution says Congress must approve a resolution of some kind, or "declare war," before utilizing military troops overseas.

Lawmakers on the left and right have long argued that old AUMFs approved in 2001 after 9/11 and 2002 for Iraq are calcified and outmoded. But why would the U.S. need to approve a new AUMF if the U.S. wasn’t at war?

Well, truth be told, the United States has kind of been a little bit "at war" ever since 9/11. Hence, the 2001 AUMF. The U.S. is still combating elements of terrorism overseas – even though the U.S. formally withdrew from Afghanistan last summer.

But why a new AUMF?

BIDEN, DEMOCRATS STRUGGLE TO KEEP PARTY ON SAME PAGE ABOUT ‘DEFUND THE POLICE’

The contours for a congressional authorization are murky at best. One could argue that portions of the 2001 AUMF serve as justification for the U.S. raid last week in Syria against an ISIS leader. But ISIS didn’t even exist when Congress approved that AUMF to invade Afghanistan and take on al Qaeda following 9/11. Many Democrats – and some Republicans – suggest that multiple presidential administrations have abused AUMF’s for decades now. They say the administrations of Presidents George W. Bush, Obama, Trump and even Biden have leaned on these older AUMFs as a crutch when they need to act overseas. And it’s either inconvenient or too cumbersome to appeal to Congress for a constitutional blessing.

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi of California speaks during her weekly press conference, Jan. 20, 2022, at the Capitol in Washington. (Rod Lamkey/Pool via AP)

A failure to fully repeal these AUMFs means various administrations can do basically anything they want when it pertains to war powers – and cut Congress out of the deal.

That’s why Pelosi would like a new AUMF. The House repealed the Afghanistan and Iraq AUMFs last year. The Senate may never take up the Afghanistan authorization. However, the Senate was slated to at least vote on repealing the Iraq resolution in December – before a tight calendar squashed it.

DEMOCRATIC REP. JAMAAL BOWMAN CAUGHT MASKLESS IN NEW YORK HIGH SCHOOL WITH MASKED STUDENTS

Rep. Barbara Lee, D-Calif., was the only member of the House to vote against the Afghanistan AUMF in the fall of 2001 – days after 9/11. But Congress is a different place than it was nearly 21 years ago. There are a lot more progressive members in Congress these days. And their voices are louder. Many of these members are leery of the U.S. infusing itself militarily around the globe. They demand clarity on U.S. operations overseas – to say nothing of the Biden administration "forward deploying" thousands of troops into Germany and parts of Eastern Europe as Russia rattles sabers over Ukraine.

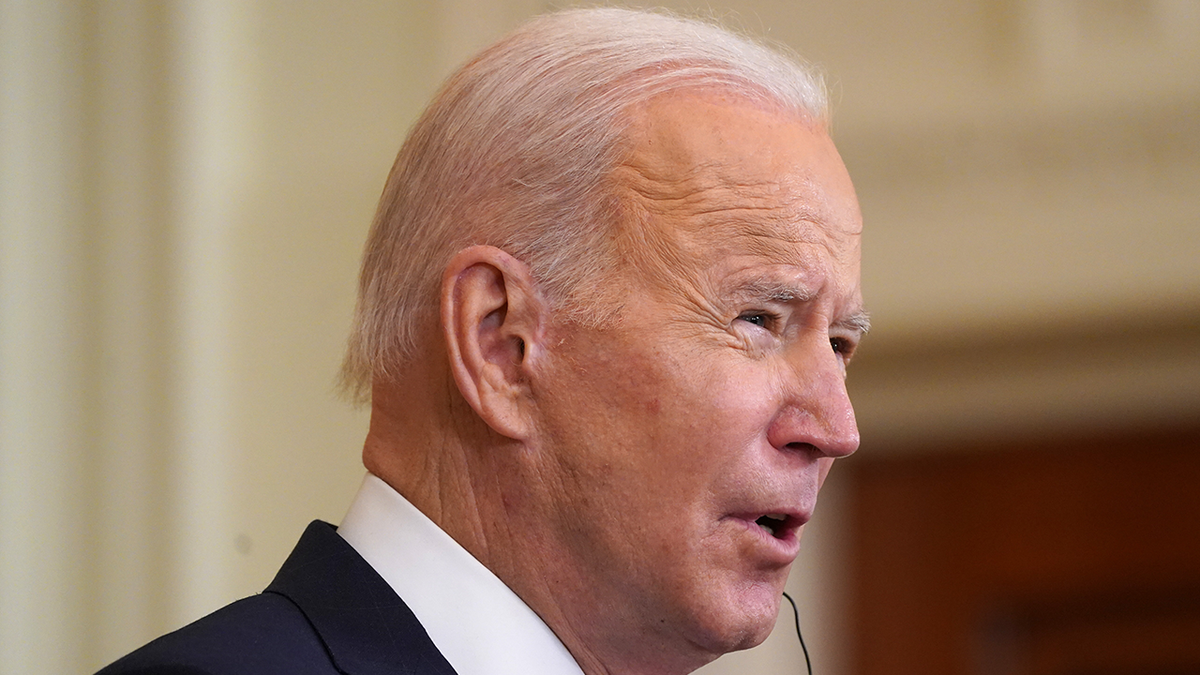

President Biden speaks during a news conference with Olaf Scholz, Germany's chancellor, not pictured, in the East Room of the White House in Washington, on Monday, Feb. 7, 2022. Biden met with Scholz to discuss the situation with Ukraine amid questions over Germany's resolve to stand firm against Russia. (Leigh Vogel/UPI/Bloomberg via Getty Image)

"There is no military solution of out of this crisis," said Lee and Progressive Caucus Chairwoman Rep. Pramila Jayapal, D-Wash., in a joint statement. "Diplomacy needs to be the focus."

The Biden administration is clear that U.S. troops won’t set foot on Ukrainian soil. The White House and Pentagon say the forces are there to support NATO allies. But things start to get tricky anytime troops are moved abroad.

WHY BUILD BACK BETTER IS BOTH DEAD AND ALIVE

"I think Congress has not been consulted sufficiently," said Jayapal to Fox. "A lot of those things do need to have more congressional consultation."

Such concern just doesn’t reside on the left. Some conservative members are also leery of an "interventionist" America when it comes to troops and the need for Congress to exercise its constitutional authority over war powers.

Rep. Pramila Jayapal, D-Wash., speaks during a House Judiciary Committee markup of the Ending Forced Arbitration of Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment Act of 2021 and other legislation in Rayburn Building, Nov. 17, 2021. (Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images)

"I’m concerned they’re starting to put gasoline on the fire," said Sen. Roger Marshall, R-Kan., after Biden administration officials briefed senators about Ukraine at the Capitol. "I think we need to roll back some of those previous authorizations of military force. I’m ready to roll back several of them. I want there to be more consulting with Congress. And I certainly don’t want any troops going to (sic) Ukraine."

Sen. Mike Braun, R-Ind., echoed Marshall.

"I am strongly opposed to President Biden’s decision to send American troops to Eastern Europe to defend countries that should defend themselves, potentially involving us in another conflict after just ending a 20 year war," said Braun in a statement.

When discussing the need for a new, broad AUMF, Pelosi said Congress and the administration must settle on "the purpose. What is the scope? What is the timetable? And what is the geography?"

Getting Congress to agree on anything like that is a Herculean task.

Which brings us back to "forward deploying" troops to Europe.

Pelosi was clear that, in her view, Congress doesn’t need to approve a new authorization to dispatch troops to Europe.

"They are a confidence builder for our allies and are there, if need be," said Pelosi.

The "need be" part speaks volumes. Especially since Pelosi noted that "you don’t have, nor do I, a definition of what the purpose of those (troops) are there (for)."

This is precisely the type of sketchy area that poses conundrums for "war powers," be they under the constitutional aegis of Congress or the president of the United States.

"Sometimes things move in unexpected directions. You’re moving troops around. What happens if there’s an accident? Something unintentional and U.S. troops are involved in fighting and something escalates?" questioned Chris Edelson, a war powers expert at American University.

This is what unfolded in 1992 and 1993 with "Black Hawk Down." Congress did not approve a resolution to allow the administration of President George H.W. Bush to send troops into Somalia near the end of his term to help with food relief. The operation then bled into the new administration of President Clinton. By October 1993, guerillas shot down two American Black Hawk helicopters. The battle killed 19 Americans. Some bodies of American troops were dragged through the streets of Mogadishu on live TV.

That episode – and the intensity of the graphic pictures – prompted Congress to immediately yank the funding for the Somalia operation.

In other words, you never know when a mission will devolve into something much more dangerous.

"We’ve watched the crisis in Ukraine unfold over several months. There’s plenty of time for the president to coordinate with Congress," said Edelson. "We live in a constitutional system where no one branch has complete power. It’s not constitutionally permissible for the president to have a monopoly over these decisions."

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Congress sometimes abdicates its war powers responsibilities because it’s easier to take a pass – and foist it all on the president. That is, until things go south. That’s when Congress wants to assert its authority.

The U.S. is still operating off stale AUMFs from 2001 and 2002. Congress hasn’t approved a new AUMF because no one can cobble together the support on Capitol Hill for one that would pass. Meantime, the U.S. is moving troops around Europe – without any direct blessing from Congress.

As Pelosi says, there may be no need for a resolution regarding U.S. action in Europe. But you can bet that Congress will demand a say if things spiral out of control.