House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., on Tuesday announced the launch of an official impeachment inquiry into President Trump. This, amid an increasing clamor over a whistleblower’s complaint that Trump may have sought the help of a foreign government in his bid for reelection.

The announcement of the inquiry marked early concrete steps by Congress, as some Dems call for his removal from office. But the full impeachment process, by design, is a long and multifaceted affair, not undertaken lightly. It could require months – and a great deal of political capital and partisan infighting – to run its course.

PELOSI ANNOUNCES FORMAL IMPEACHMENT INQUIRY AGAINST TRUMP

Here is how impeachment proceedings are launched and what it would take to actually remove a president from office.

How it works:

The framers of the Constitution established impeachment as a way to hold a president accountable for abuses of power. The Constitution lays out some specific actions – think treason, or bribery – that would lead to impeachment and removal from office, and affords the president a trial to determine whether or not he's guilty.

Along with treason and bribery, the president can be accused of “high crimes and misdemeanors.” That's a rather vague term borrowed, as is so much of the language on impeachment, from British common law dating back to the 14th century.

The term “high crimes and misdemeanors” was controversial when George Mason inserted it as a provision in the Constitution in 1787 and the phrase has confounded lawmakers and constitutional scholars ever since.

While what makes an offense impeachable is debatable, the process for impeaching a president and removing him from office is fairly straightforward, albeit lengthy.

Pelosi’s announcement of an impeachment inquiry from the House committees does not mean that the lower chamber of Congress will actually take up a resolution to impeach Trump – just that there's a plan to probe the whistleblower’s complaint surrounding the president’s phone call with newly elected Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky.

If lawmakers in the Democratically controlled House decide, however, to move forward with impeachment proceedings, the first step would be for a member of the lower body to introduce a resolution to impeach Trump. During the Watergate scandal of the early 1970s, the House didn’t even get this far; President Richard Nixon, facing mounting pressure from lawmakers and extreme unpopularity among the American public, resigned.

REP. AL GREEN WARNS DEMS: 'THE PUBLIC IS GOING TO TURN ON US' IF WE DON'T IMPEACH TRUMP

After introduction, Pelosi would have to direct House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jerry Nadler, D-N.Y., to hold a hearing to decide if the resolution will be put to a vote by the full chamber. Nadler would need only a simple majority in the committee to send the resolution to the House floor for a full vote.

Simple majorities

On the floor, all that is needed to actually impeach the president is another simple majority vote by those lawmakers present and voting. This is what happened to President Bill Clinton in 1998, when he was impeached by the House on the charges of lying under oath and obstruction of justice.

Clinton and Andrew Johnson are the only two American presidents to be impeached in the House.

Misconception

Just because a president is impeached, however, removal from the Oval Office is hardly a certainty. That is a matter to be decided during the president’s “trial” in the Senate.

The trial is meant to decide whether the president has committed a crime; the procedure for the trial is set by Senate leadership.

GIULIANI ACCUSES UKRAINE OF LAUNDERING $3M TO HUNTER BIDEN, ASKS HOW OBAMA COULD LET THAT HAPPEN

During the trial, House lawmakers serve as so-called “managers,” who basically fill the role that prosecutors would in a criminal trial and present evidence against the president. The president is represented by his own counsel.

The chief justice of the Supreme Court presides over the trial and the Senate acts as the jury – listening to the arguments from both sides before deliberating and voting on whether to remove the president from office. It takes a two-thirds vote to convict a president; with a finding of guilt, the president is removed from office and the vice president is sworn in to replace him.

How we got here:

Trump’s controversial conversation with the Ukrainian president is not the first time that the idea of impeaching him has been mentioned. Indeed, the specter of impeachment has loomed over his presidency since before he ever took office.

Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 presidential election and calls from Democrats that Trump obstructed justice. Multiple tries by Rep. Al Green, D-Texas, to bring forth articles of impeachment. Billionaire Tom Steyer’s Need to Impeach campaign. All that and more has clung to the Trump administration.

But Pelosi’s announcement of a formal impeachment inquiry marks the first time the House speaker has yielded to the demands of fellow Democrats on the matter. Pelosi previously has been extremely reticent even to discuss impeachment – worried that it would hurt Democrats' chances of taking back the White House in 2020 – so her announcement on Tuesday marked a major shift.

So, what led to the change?

Despite the phone call with Ukraine’s Zelensky taking place this past July, the impetus for the current impeachment push actually goes back to June, when Trump said during an interview that he would consider accepting damaging information about a political opponent from a foreign government without first notifying the FBI.

"I think you might want to listen, there isn't anything wrong with listening," Trump told ABC News. "If somebody called from a country, Norway, [and said] 'we have information on your opponent' -- oh, I think I'd want to hear it."

FLASHBACK: IN APRIL, TRUMP SAYS HILLARY-UKRAINE COLLUSION ALLEGATIONS 'BIG,' WILL BE INVESTIGATED

A few days later, the Defense Department announced $250 million in aid to Ukraine, but by mid-July Trump told acting Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney to put a hold on the disbursement, with administration officials declining to give lawmakers more information on the matter.

A day after Mueller testified before Congress on his Russia probe, Trump conducted what he called a “routine” phone call with Zelensky, which prompted the whistleblower’s complaint that Trump pushed Ukraine's leader for help investigating former Vice President Joe Biden -- a Dem frontrunner in the 2020 election -- and Biden's son Hunter.

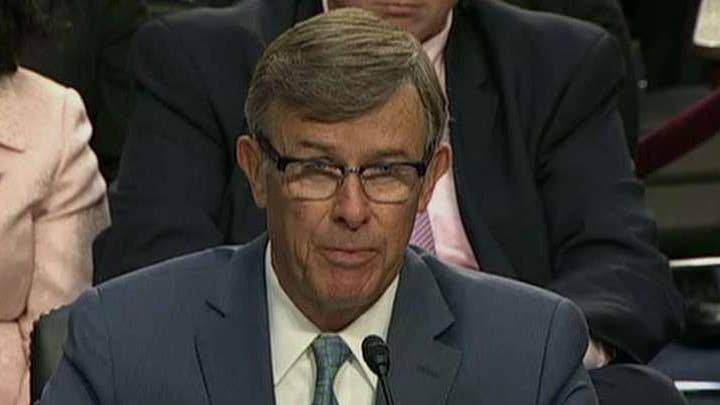

Three days after the phone call, Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats resigned and Trump named National Counterterrorism Center Director Joseph Maguire his acting DNI.

On Aug. 12, the unnamed whistleblower filed a complaint to Michael Atkinson, the inspector general for the intelligence community, who in turn passed it on to Maguire. The acting DNI, however, did not alert Congress within the one week allotted to report the complaint, which forced Atkinson to send a letter to House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff and Ranking Member Devin Nunes.

Schiff sent a formal letter on Sept. 10 asking for the complaint, but three days later, Maguire denied the request and Schiff issued a subpoena.

CLICK HERE FOR THE FOX NEWS APP

The news of the complaint emerged publicly last week, and while Trump originally tried to shift the focus toward his allegations against Biden, he ultimately acknowledged he discussed Biden during his call but deflected on whether he wanted any damaging information on the former vice president.

"The conversation I had was largely congratulatory, with largely corruption, all of the corruption taking place and largely the fact that we don't want our people like Vice President Biden and his son creating to the corruption already in the Ukraine,” Trump said.