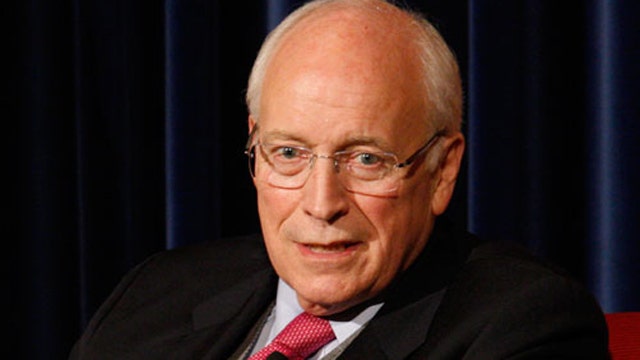

Dick Cheney rips Obama administration in Playboy interview

Former vice president warns of fallout from 'crippling' foreign policy

In December 2005, then as now a reporter for Fox News, I accompanied Vice President Cheney on an official trip to some exotic -- and important -- locales: Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, each critical to the war on terror then still in its early years. Overshadowing the vice president's itinerary, to some extent, was the disclosure on Dec. 16, by the New York Times' James Risen, of the Bush administration's Terrorist Surveillance Program, the initiative by which federal officials had monitored the communications of suspected terrorists, including calls involving American citizens, with the use of "warrantless" wiretaps.

My relationship with Cheney at the time was cordial but not deep. I had covered the White House for Fox News, as one of the junior members of our White House team, since the last year of the Clinton presidency, and had been around. I had covered an earlier trip of his -- the first foreign travels of his vice presidency -- in early 2002, when he had traversed the Middle East, 12 countries in 10 days, looking to secure Arab support for the Iraq war and instead receiving, at each stop, an earful about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He and the members of his team, including his national security adviser, Scooter Libby, had been generous with their insights in background and off-the-record sessions. They knew me and I knew them.

Following the customary protocol for such trips, each of the TV news correspondents along for the ride was to receive his or her own sit-down with "the principal" -- in this case, the individual who was understood, even then, to be the most powerful and controversial vice president in American history. Given Cheney's unique stature, it was further understood, universally, that an interview with him was not like securing an interview with any other vice president. It was coveted almost as much as an interview with the president himself.

Except I never got one. Dana Bash, the CNN correspondent covering the trip, conducted hers on the side of a snowy mountain in Pakistan, where Cheney visited a MASH unit tending to victims of a recent massive earthquake. But the trip was abruptly cut short so that the vice president could return to Washington and cast the tie-breaking vote in a deadlocked United States Senate (a vote that ultimately never occurred). Steve Schmidt, the Republican strategist who was running communications for Cheney at the time (later of "Game Change" fame), assured me that the vice president would conduct his interview with me when we were back in Washington. "It'll be you who does it, Rosen, we won't let anyone Big-Foot you," he said. "We promise."

Two months went by, and then Cheney accidentally shot his friend, Harry Whittington, during a hunting trip in South Texas. Cheney's next interview with Fox News turned out to be a dramatic sit-down with our managing editor and chief anchor at the time, Brit Hume, in which the vice president explained what had happened and why he had initially kept mum about the incident. I knew then it would be a long time, if ever, before I would get my chance to interview this singular figure in American history.

It took, in fact, a decade. In the interim, Cheney conducted exit interviews when he left the White House, and promotional interviews when he published each of his two books, "In My Time: A Personal and Political Memoir" (2011) and "Heart: An American Medical Odyssey" (2013). Throughout each of these cycles, I was never one of the anointed.

Finally, I ran into the vice president and his wife, Lynne, in April of last year, at the annual party that my new Fox News colleague, George Will, hosts to celebrate the opening of baseball season. After enduring some good-natured ribbing by Cheney about my recent notoriety as the subject of investigation by Attorney General Eric Holder and the Department of Justice, I switched topics: "You know, I've got a bone to pick with you, Mr. Vice President." His face lit up with surprise. I reminded him of the 2005 trip and The Interview That Never Was.

"If we were to amortize the seven-and-a-half to ten minutes I'd have received in 2005," I continued, "I think we'd be up to something like twenty-eight hours of Nixon-Frost-style interviews today, sir." Cheney laughed and asked me to contact his daughter, Liz, who has long played an integral role in her father's activities, to set something up.

That turned out to be a two-hour lunch, just the two of us, at a steakhouse near the Cheney residence in Northern Virginia. I was startled when the former vice president strode in and tapped me on my shoulder as I sat in a booth, removing his cowboy hat and greeting me with that sly grin. "Jim!" he said courteously. Fully aware of his long history of cardiac issues, I told him in advance: "Sir, I'm going to order a big, fat steak. I'm going to have them cook it in butter. It's going to be a scene over on this side of the table." He smiled and ordered a salad with salmon on top of it.

In the course of those two hours, as we sketched out what an extended interview with him might cover, I discovered something surprising about Dick Cheney: Contrary to his stern image, he enjoys a good joke; and where his reputation for taciturnity has imbued him, to some, with an air of menace, he is actually quite garrulous. One stray mention of President Ford by me launched Cheney into a detailed, 20-minute soliloquy on the new Gerald R. Ford class of aircraft carriers, and the innovative suspension systems installed in them. Far from Darth Vader, my interlocutor was genial, wry, talkative, and deeply well informed.

Thus it was in the lengthy recorded sessions that yielded "The Playboy Interview with Dick Cheney," appearing in the magazine's April issue. Where Cheney had originally agreed to submit to six hours of questioning spread across three days, we wound up going long on each of the three days and ultimately recorded close to 10 hours of material. The questioning, as agreed in advance, was comprehensive in scope, spanning from Cheney's childhood and relationship with his parents through the various presidential administrations he has served and up through the present day. We started with the personal side and worked our way through the presidents Cheney has known; spent the second day wrapping up the first day's business before proceeding to Cheney's views on foreign leaders (Karzai, Musharraf, Putin), the Obama foreign policy, energy development, the digital revolution, the Tea Party, immigration, and other contemporary subjects; and we finished by zeroing in on 9/11 and its aftermath, the Iraq war, and what I called "Cheney addresses his critics," wherein I presented him with some of the harshest criticism leveled at him to date and gave him an opportunity to respond.

In all, the transcripts for "the Cheney tapes" ran to 300 single-spaced pages, encompassing roughly 80,000 words of text. The material in the Playboy interview represented approximately 7,000 words from the sessions. The remainder will hopefully someday appear in book form, in a volume that can stand alongside similar entries in the format: David Sheff's "The Playboy Interviews with John Lennon & Yoko Ono" (1981); Jann Wenner's "Lennon Remembers: The Full Rolling Stone Interviews from 1970" (2000); or Jonathan Cott's "Susan Sontag: The Complete Rolling Stone Interview" (2014). Students of Cheney, the Bush presidencies, the Watergate era and the Ford administration, 9/11 and Iraq, and modern foreign policy and economic trends will all find The Cheney Tapes of more than passing interest.

There was a small irony in my recording 10 hours of interviews with this man. On our trip to Iraq back in 2005 -- the very sojourn on which I had originally been denied an interview, and which led to the current sessions -- we toured the Taji Air Base in Iraq, where Cheney, as a gesture of solidarity with the troops, ambled along the chow line with the rank-and-file. Heaped onto his plate were Army-size servings of lamb, hummus and something that, at a glance, looked like it might be a vegetable lo mein of some sort. You could tell instantly that the famous cardiac patient was blanching at the sight of it. I leaned forward and asked him, "Has Mrs. Cheney approved all this?" He smiled that lopsided Cheney smile, and pressed an index finger to his lips, in the motion that is universally understood to convey: "Shhh."